Emotion Coaching - A Strategy for Promoting Behavioural Self-Regulation in Children/Young People In Schools: A Pilot Study

Abstract

Emotion coaching is a parenting style clinically observed in the USA which supports children’s emotional self-regulation, social skills, physical health and academic success. A pilot study in a rural disadvantaged area in England sought to evaluate the effectiveness of training practitioners who work with children and young people in schools, early years settings and youth centres to apply emotion coaching strategies in professional contexts, particularly during emotionally intensive and behavioural incidents. The study rested on the premise that supportive adults can individually and collectively empower children and young people to build a repertoire of internal and external socio-emotional regulatory skills that promote prosocial behavior. A mixed method approach was adopted (n=127). The findings suggest the efficacy of adopting emotion coaching strategies to support behavioural management approaches and policies within settings across the age range. Data from school contexts are largely recorded here. The research is the first pilot in the UK that builds on and complements similar work being undertaken in the USA and Australia.

Keywords: Emotion coaching, behaviour, self-regulation, social and emotional development, meta-emotion philosophy

Introduction

Children and young people’s behaviour, particularly in school, continues to be a cause for concern in all sectors of society from government to media to the community (Shaughnessy, 2012). Hutchings et al. (2013) have identified that behavioural problems in the classroom are growing and a DfE research report (2011a) details the increasing prevalence of children and young people (Hereafter, ‘children’ denotes children and young people) who exhibit behavioural difficulties within England. Shaughnessy has highlighted that ‘schools have been flooded with policies, initiatives and strategies for developing and sustaining positive behaviour’ (2012, p. 88). Although the previous government framed such policies within a broader perspective of well-being and mental health (enshrined in the Every Child Matters initiative, DfES, 2004), current government discourse and policy appears to be re-focusing attention on disciplinary issues and traditional approaches to managing behaviour (Gove, 2010). For example, part of the 2011 Education Act (DfE, 2011b) strengthened aspects of previous legislation in respect of teachers’ statutory authority to discipline pupils for misbehaviour. This has been re-enforced by the guidance document: Ensuring Good Behaviour in Schools (DfE 2012a) which redefines what constitutes ‘reasonable force’ that staff may use on pupils. Noted for its brevity it is also notable for its use of terms such as ‘discipline’, ‘misbehaviour’ and ‘punishment’ which had fallen into disuse in the context of behaviour in schools in recent years. Similarly, the revised Teachers’ Standards require teachers to ‘establish a framework for discipline with a range of strategies, using praise, sanctions and rewards’. Although the Standards also call for teachers to ‘maintain good relationships with pupils’ the emphasis is for teachers to ‘exercise appropriate authority, and act decisively when necessary’ (DfE, 2012b: 7). This appears to signal a return to behaviourist rather than relational approaches to managing behaviour largely based on the work of Behaviourists such as Skinner (1968). Behaviourism is based on the premise that behaviour can be controlled and modified via the reinforcement techniques of reward and sanction.

Shaughnessy (2012) has called for the need to re-focus attention on humanist approaches which acknowledge the complexity of children’s behaviour and focus on internal factors, rather than external control. She writes, ‘much time and effort is currently spent by policy-makers on the aspects of control, order and regulation of behaviour, which operates on a limited evidence base about behaviour and violence in schools’ (2012, p. 94). Such policies do not necessarily address the complexities of social and emotional needs of children, particularly those who are high-risk. Davis (2003) highlights various studies which have shown how the quality of teacher–child relationships shape classroom experiences and influence children’s social and cognitive development. How teachers respond to children’s behaviour in particular, can affect outcomes. For example, responsive, nurturing and attuned teachers are likely to diminish externalising or maladaptive behaviours (Tucker et al., 2002). Hutchings et al. (2013) have noted that more effective evidence- based interventions are needed to support school staff who are often ill-equipped to deal with more challenging behaviour.

Emotion coaching is offered as an alternative paradigm to behavioural or ‘high-control’ methods. This approach recognises that socially competent children who are able to understand and regulate their emotions are better equipped to go on to achieve higher academic success than those who lack impulse control or have poor social skills (Webster-Stratton, 2004; Graziano et al., 2007; Linnenbrink-Garcia & Pekrun, 2011). The traditional separation of cognition from emotions has now been superceded by evidence that shows how thinking and reasoning and emotional processing are fundamentally integrated in the brain at multiple levels (Goswami, 2011; Immordino-Yang & Damasio, 2007). Our emotions and relationships influence our motivation and give meaning to our knowledge formation (Freiler, 2008). To promote learning, educators need to engage the affective domain of their pupils’ minds and attend to their affective needs to maximise success at school through positive relationships (van der Hoeven et al., 2011, Shaughnessy, 2012). MacCann et al.’s (2010: 60) research also suggests that better educational outcomes are achieved by ‘targeting skills relating to emotion management and problem-focused coping’, i.e. emotional and behavioural self-regulation. Weare and Gray’s (2003) comprehensive review has also identified that interventions which teach social and emotional competencies can help to reduce behaviour problems. Indeed, ‘emergence of behaviour problems has been linked to poor emotional competence in children, specifically problems in understanding and regulating emotions’ (Havighurst et al, 2013, p. 248). Success is now believed to be as much to do with socio- emotional and self-regulatory capacities as academic skills and knowledge (Heckman et al, 2006; Boyd et al, 2005), and reviews of the literature reflect the evidence which suggests ‘effective mastery of social-emotional competencies is associated with greater well-being and better school performance’ (Durlak et al, 2011, p. 406).

Emotion Coaching – a relational and skills-based approach to supporting children and young people’s behavior

Emotion coaching is based on the work of Gottman and Katz and colleagues (Gottman et al., 1996) and is essentially comprised of two key elements - empathy and guidance. These two elements express themselves through various processes which adults undertake whenever ‘emotional moments’ occur. Emotional empathy involves recognizing, labeling and validating a child’s emotions, regardless of the behaviour, in order to promote self-awareness and understanding of emotions. Such acceptance by the adult of the child’s internal emotional state creates a context of responsiveness and security, and helps the child to engage with more reasonable solutions. The circumstances might also require setting limits on appropriate behaviour (such as stating clearly what is acceptable behavior) and possible consequential action (such as implementing behavior management procedures) - but key to this process is guidance: engagement with the child in problem-solving in order to support the child’s ability to learn to self-regulate - the child and adult work together to seek alternative courses of action to help manage emotions and prevent future transgressions. This process is adaptable and responsive to the developmental capabilities of the child, with the adult scaffolding pro-social solutions and differentiating where necessary. By enabling children to tune in more explicitly to their emotions and problem-solve solutions that will help them to manage such feelings, and the behavioural consequences of those feelings, the child is engaged in pro-actively enhancing social and emotional competences. It also supports the child’s development of ‘meta-emotion’, which refers to the ‘organised set of feelings and cognitions about one’s own emotions and the emotions of others’ (Gottman et al, 1997:7). Thus, emotion coaching helps to instil the tools that will aid children’s ability to self-regulate their emotions and behaviour (Shortt et al., 2010).

The main research evidence base for emotion coaching comes from America and Australia. Randomised Control Trials in America have demonstrated that emotion coaching enables children to have better emotional regulation, more competent problem-solving, higher self- esteem, better academic success, more positive peer relations and fewer behavioural problems (Gottman et al., 1997). Emotion coaching has been used to support children with conduct behavioral difficulties ( Havighurst et al., 2013; Katz & Windecker-Nelson, 2004), depression (Katz & Hunter, 2007) and those exposed to violent environments, including inter-parental violence, maltreatment and community violence (Shipman et al., 2007, Katz et al, 2008; Cunningham et al, 2009). Emotion coaching has also been positively correlated with secure attachments (Chen et al., 2011), and used effectively to improve the psychological functioning of children who have experienced complex trauma (Murphy et al., forthcoming), as well as reduce the externalising behaviours of children with ASD (Wilson et al., 2013). It has also recently been identified as a protective factor for children with ODD (Dunsmore et al., 2012) and for children at risk (Ellis et al., 2014).

Problem Statement

Research on emotion coaching is relatively limited and scarce in the UK, and there has been little research undertaken on the use of emotion coaching in professional contexts (Katz et al., 2012; Ellis et al., 2014, Wilson et al., 2012). Katz et al.’s (2012) recent review of emotion coaching research calls for more studies that explore the role of emotion socialisation agents other than parents, such as teachers and peers. Productive interactions between individuals are fundamental to effective educational practice, and teachers have identified that emotional management is integral to their work (Gross, 2013; Day et al., 2006; Nias, 1996; Sutton et al., 2009), yet the exact training needs and skill base on which to support the development of reflective, emotional competencies are yet to be identified (Ahn & Stifter 2006; Jakhelln, 2010; OFSTED, 2013).

Purpose of the Study/Research Question

The key research question guiding the pilot project was: ‘What is the effectiveness of using emotion coaching in professional practice within community settings?’. The main aim of the project was to promote the use of emotion coaching techniques as a shared, consistent strategy by community groups (particularly in educational contexts) in work with children, and to support children’s capacity for pro-social behaviour. We were therefore interested in ascertaining whether emotion coaching might reduce incidents of negative externalizing behaviour and promote a more relational and skills-based approach to supporting children’s behaviour.

Part of the project’s training sought to explore the adults’ meta-emotion philosophy and engage in discussion about their own beliefs and attitudes towards their own and others’ emotions, as well as their perceptions of children’s behaviour and the underlying emotional functioning that might generate certain behaviours. Therefore, the project also sought to identify whether or not the adoption of emotion coaching might alleviate ‘emotion dismissing’ amongst adults working with children. Gottman et al.’s (1996) initial research on emotion coaching drew attention to less effective ways of supporting children’s emotional regulation and subsequent behaviour. Parents who are ‘disapproving’ or ‘dismissive’ of children’s emotions tend to ignore, criticize or reprimand affect displays, particularly intensive emotions, which may often manifest as challenging behavior. Such parents may view stress-induced emotional expression as a form of manipulation, a form of weakness and/or something that should be avoided or minimized (collectively known as ‘emotion dismissing’). An emotion dismissing parenting style, whether disregarding or punitive, has a negative impact on children’s emotional regulation and behavioural outcomes (Gottman et al., 1996). These alternative styles of interaction correlate with the findings from the wealth of research which has extensively explored the consequences of insensitive and unresponsive parenting (see Havighurst et al., 2013).

Research Methods

The pilot study took place in two parts over a period of 2 years. Funding limitations precluded the adoption of RCTs but a mixed methods approach generated both quantitative (descriptive and inferential statistics) and qualitative data as indices of effectiveness (Johnson and Christensen, 2012). Participants (n=127) were recruited from early years settings, schools and a youth centre within a disadvantaged rural town (Part 1) and a vulnerable rural area with a high population of military families (Part 2). Participating institutions included 1 secondary, 4 primary schools, 4 children’s centres and 1 youth centre for Part 1 of the pilot (year 1) and 1 secondary school and 5 primary schools for Part 2 of the pilot (year 2). Participants included senior and junior teaching staff, teaching assistants, school support staff, Children’s Service staff including health and social care services, early years practitioners, youth workers and youth mentors, and some parents. The bulk of the data were, however, drawn largely from the 11 schools and the majority (80 %) of participants were education staff (largely teachers). Moreover, the behavioural case study was focused on one school. We have therefore focused the presentation of our findings here on the use of emotion coaching in the school context. Findings that focused on the Children’s Centres and Youth Centre can be found elsewhere, along with findings from two cohorts of young people (n= 64) who were trained in emotion coaching techniques as part of a peer mentoring programme (Rose et al., 2012; Gilbert et al., 2014; Rose et al., forthcoming).

In both parts of the pilot study, participants were trained in emotion coaching techniques (the training phase) and supported via four network/booster meetings (the action research phase) to adopt, adapt and sustain emotion coaching into their practice over a period of one year for each setting (Gilbert, forthcoming). The action research phase was intended to address some of the identified challenges of bringing about educational change (Fullan, 2007; Elliot, 1991). Ethical protocols were upheld in accordance with the authors' institutional research ethics regulations (BSU, 2011) and in accordance with British Psychological Society (2011) ethics guidance.

Training Phase

•Two session workshop training adopted an active learning, multisensory approach with multimedia tools to support and illustrate neuroscience, physiological processes, attachment theory, meta-emotion philosophy and the development of emotion coaching skills.

•Training content and process was adapted for different contexts and participant groups for resonance and to promote a sense of ownership.

•All staff in settings were trained where feasible.

Action Research Phase

•Over a period of one year, participants adopted emotion coaching techniques into everyday adapting them to their own contexts.

•Additional input was also given by the research team at network/ booster meetings regarding clarification of emotion coaching techniques and to provide general support where necessary.

•The network/booster meetings between participants and the research team provided a forum for developing the application of emotion coaching within practice, for sharing experiences and for exploring the complexities and challenges of adopting emotion coaching into practice.

Research Instruments

Impact of the use of emotion coaching in professional practice was to be determined by evidence of improved meta-emotion philosophy and adult self-regulation, improved exchanges between adults and children that reflect a relational model of behaviour management, and improved self-regulation and pro-social behaviour by children. The research instruments used included pre and post-impact psychometric questionnaires with all participants, exit questionnaires with all participants, pre- and post- training behaviour indices and oral recordings of the network/booster meetings and focus group discussions.

Pre-and post-training Emotion Coaching Questionnaires (quantitative)

Pre- and post- training Emotion Coaching Questionnaires were used to determine differences in meta-emotion philosophy. Two versions of the pre- and post- training Emotion Coaching Questionnaires were produced. The first version (V1) of the Emotion Coaching Questionnaire consists of 60 item stem questions with a 5-point Likert scale response options. For instance, participants were asked to rate on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) to the item stem: ‘When a child / young person is angry, I help him / her to identify / name the feeling’. The questions were based on adaptations of evaluation tools to measure meta-emotion philosophy developed by others, such as the Emotion Coaching Questionnaire and Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (Gottman et al., 1996, Lagace-Seguin & Coplan, 2005). The Emotion Coaching Questionnaire was administered at two points in time: pre-training and one academic year post- training in Part 1 of the pilot study. To refine the Emotion Coaching Questionnaire further, a Principal Components Analysis (PCA) was conducted on the 60-item scale (V1) to reduce the tool to the most discriminating items (McGuire-Snieckus et al., forthcoming). A shorter version of the Emotion Coaching Questionnaire (V2) with 41-items was produced which represented the most discriminating items and was administered in Part 2 of the pilot study pre- and post- training (one academic year).

Exit Questionnaires (quantitative)

The Exit Questionnaire was compiled to obtain additional feedback from participants regarding impact. The items compiled in the Exit Questionnaire were derived from claims made by the participants about the use of emotion coaching during the focus group discussions and completed by all participants (Johnson & Christensen, 2012). The preliminary qualitative analysis identified 23 statements (items) of practitioner perspectives related to the impact of emotion coaching with yes/ no response options, in order to ascertain whether the views expressed during focus group discussions were shared by all participants across the settings. An example of how an item stem was informed by the participants’ experiences is now described. A common statement by practitioners during a focus group discussion in Part 1 of the project was ‘I’m more consistent in the way I respond to pupils’ behaviour now’. These types of coded statements were then transformed into the following item stem: ‘Do you think emotion coaching helps you to have a more consistent response to pupils during incidents?’. Post research Exit Questionnaires were collected at one time point after post-training (one academic year). Minor adaptations were made to suit setting context e.g. replacing the term ‘pupils’ with ‘young children’.

Evidence of impact on practice – Focus group and Exit Questionnaire free-text responses (qualitative)

The Exit Questionnaire included semi-structured open response items that queried participants’ views on how emotion coaching had affected practice as well as possible benefits and challenges of applying the tool in practice. As noted in point 2, the items were derived from claims made by participants during the focus discussions. Questions posed during focus group discussions were informed by Gottman et al.’s (1997) meta-emotion philosophy’s theoretical framework and designed to elicit how emotion coaching had affected participants’ own emotional understanding, self-regulation and its effectiveness in terms of the impact on the child, particularly their emotional and behavioural self-regulation. The network/booster sessions also recorded incidents when emotion coaching was used in practice but these data are recorded elsewhere (Gilbert et al., 2014).

Evidence of impact on practice - Pre-and post- training behavior indices (quantitative)

Possible pre- and post- emotion coaching training changes in pupil behaviour indices (call-outs, exclusions, consequences and rewards) at 1 case study secondary school of 1350 pupils were explored regarding disruptive behaviour: call-outs (incidents where children are called out of the classroom), exclusions (external exclusion from school), consequences (sanction applied), and rewards (reward applied). Differences in mean behaviour indices pre- and post- training were assessed. This data was supplemented by behavioural tracking of six case study children – four 13 year old boys and two 15 year old girls, who were identified by the staff as ‘at risk of exclusion’.

Data Analysis

The quantitative data (pre- and post- Emotion Coaching Questionnaires, Exit Questionnaires, behaviour indices) were analysed using SPSS (V21) and Excel. Both versions of the pre- and post- Emotion Coaching Questionnaires (V1 and V2) were administered at two points in time: T1 = one academic year pre-training and T2 = one academic year post-training by separate samples. A paired sample t-test (Ferguson and Takane, 1989) was applied to the Emotion Coaching Questionnaire data for each questionnaire version. Exit Questionnaires were collected at one time point one academic year post-training. Chi-square analysis (Ferguson & Takane, 1989) was utilised for the analysis of the Exit Questionnaire data.

The qualitative data (focus group discussions, free-text responses in Exit questionnaires) were analysed using inductive coding (Creswell, 2002), largely utilising constructivist grounded theory and constant comparative method (Charmaz, 2006; Strauss & Corbin, 1990). Narrative analysis was also applied in order to explore the content of the focus group discussions and the structure of the participants’ stories about emotion coaching usage (Riessman, 2008).

Differences in mean behaviour indices (call-outs, exclusions, consequences and rewards) collected by the school for one academic year pre-training and for one academic year post-training were explored. Paired sample t-tests (Ferguson & Takane, 1989) were applied to the pre- and post- training behaviour data.

Analyst triangulation (Guba & Lincoln, 1985) was utilised for both the qualitative and quantitative analysis, including the use of 3 independent statistical and qualitative analysts.

Findings

Evidence of changes in meta-emotion philosophy of participants - Pre-post Emotion Coaching Questionnaires (quantitative)

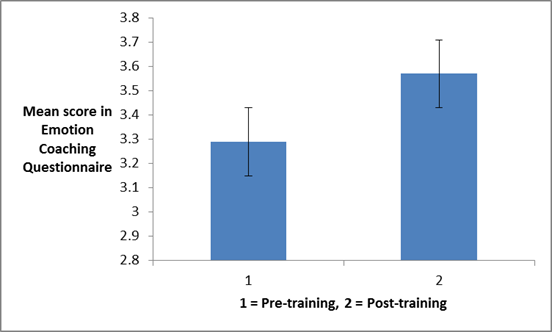

56 matched pairs (participants identified as completing both the pre- and post- training questionnaires) were collected. Using version 1 (V1) of the Emotion Coaching Questionnaire, a paired-samples t-test was conducted to evaluate the difference in emotion coaching scores pre- and post- training. There was a statistically significant increase on participants’ scores on the Emotion Coaching Questionnaire (V1) from Time 1 (M = 3.29, SD = .55) to Time 2 (M = 57, SD = .32), t (55) = 3.44, p < .01 (two-tailed). These means are depicted in Figure 1. The mean increase in emotion coaching scores was .28 with a 95% confidence interval ranging from .12 to .44. The eta squared statistic (0.18) indicated a small effect size (Cohen et al, 2007), with a small difference in the emotion coaching scores obtained before and after the training.

To refine the Emotion Coaching Questionnaire further, a Principal Components Analysis (PCA) was conducted on the 60-item scale (V1) to reduce the tool to the most discriminating items (McGuire-Snieckus et al., forthcoming) for part 2 of the pilot study. A shorter version (V2) 41- item second version of the Emotion Coaching Questionnaire was created.

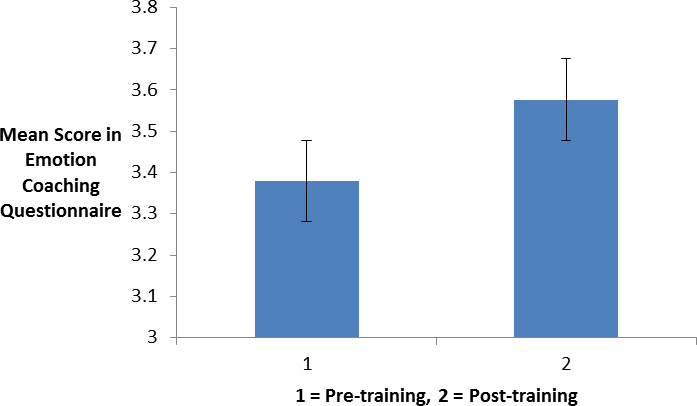

Using the second version (V2) of the Emotion Coaching Questionnaire with a sample of 59 participants, a paired-samples t-test was conducted to evaluate the impact of the emotion coaching training on participants’ mean item scores on the Emotion Coaching Questionnaire. There was a statistically significant increase in Emotion Coaching Questionnaire (V2) scores from pre-training (M = 3.38, SD = .28) to post-training (M = 3.58, SD = .35), t (58) = 3.73, p < 0.001 (two-tailed). The mean increase in Emotion Coaching Questionnaire scores was .20 with a 95% confidence interval ranging from 0.30 to 0.09. The eta squared statistic (0.19) indicated a small effect size (Cohen et al, 2007). The pre- and post- training mean item scores on the Emotion Coaching Questionnaires (V2) are provided in Figure 2.

Results from V1 and V2 suggest an increase in emotion coaching meta-emotion philosophy and a reduction in emotion dismissing meta-emotion philosophy.

Evidence of impact on practice - Exit Questionnaires survey data (quantitative)

In total, 127 participants completed the Exit Questionnaire. A Chi square goodness of fit test was applied to the overall Exit Questionnaire data. The value of Χ2 obtained (1407.66) when df= 1, was significant at the 0.001 level of probability. Thus it can be concluded that there is a statistically significant difference in the direction of responses with more positive item responses (2373) than negative item responses (398) with regards to how effective the participants felt emotion coaching has been. The percentage of positive to negative responses was 86% and 14%, respectively.

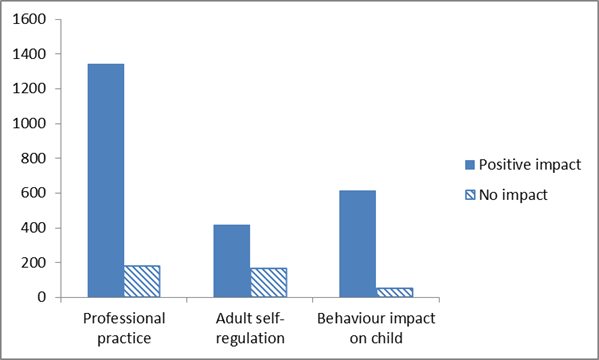

To explore further, for what aspects the participants found emotion coaching to be most effective, the items of the questionnaire were divided into groups by their conceptual relevancy. The resulting three groups were Professional practice (PP), Adult self-regulation (AS) and Behavioural impact on child (BIC). A Chi square goodness of fit test was applied to the items relating to professional practice on the Exit Questionnaire. The value of Χ2 obtained (880.48) when df= 1, was significant at the 0.001 level of probability. Thus it can be concluded that there is a statistically significant difference in the direction of responses with more positive item responses (1341) than negative item responses (182) with regards to how effective the participants felt emotion coaching has been with respect to professional practice. The percentage of positive to negative responses is 88% and 12%, respectively. A Chi square goodness of fit test was applied to the items relating to adult self-regulation on the Exit Questionnaire. The value of Χ2 obtained (109.11) when df= 1, was significant at the 0.001 level of probability. Thus it can be concluded that there is a statistically significant difference in the direction of responses with more positive item responses (417) than negative item responses (165) with regards to how effective the participants felt emotion coaching has been with respect to adult self-regulation. The percentage of positive to negative responses is 72% and 28%, respectively. A Chi square goodness of fit test was applied to the items relating to behavioural impact on the child on the Exit Questionnaire. The value of Χ2 obtained (477.62) when df= 1, was significant at the 0.001 level of probability. Thus, it can be concluded that there is a statistically significant difference in the direction of responses with more positive item responses (615) than negative item responses (51) with regards to how effective the participants felt emotion coaching has been with respect to behavioural impact on the child. The percentage of positive to negative responses on this dimension is 92% and 8%, respectively. The proportion of positive to negative responses by conceptual relevance is provided in Figure 3.

Results indicate a positive impact on professional practice, adult self-regulation and improvements in children/young people’s self-regulation and behaviour.

Evidence of impact on practice - Exit Questionnaires free-text and focus groups (qualitative)

From the analysis of the qualitative data gathered from the Exit Questionnaires, three overarching and interlinked themes emerged which correlated with the quantitative findings reported in section 2 – the impact on professional practice (PP), the impact on adult self-regulation (AS) and the behavioural impact on children/young people (BIC). These data provided a rich narrative of practitioners’ perceptions of the impact of emotion coaching training on their own practice, on their own self-regulation and the impact on children/young people’s behaviour. These findings concur with the quantitative data recorded in section 1 which suggested decreases in ‘emotion dismissing’ by adults and in section 4 which suggests reductions in behavioural incidents. Quotes from participants are used for illustration and are all taken from education staff from both the primary and secondary schools (teachers, teaching assistants, support staff).

Theme 1 – Professional Practice (PP)

The key finding from this theme is: Emotion coaching enables adults to communicate more effectively and consistently with children in stressful situations, to utilise less ‘emotion dismissing’ approaches, and helps to de-escalate volatile situations.

Echoed by many, one practitioner noted that to behavioural incidents without going. This was recognised by another participant as of universal benefit, in that Practitioners believed that emotion coaching

Participant views reflected the various processes involved in applying emotion coaching techniques. For example, one noted how she was and another commented: One practitioner also testified to how emotion coaching helped her to be less ‘emotion dismissing’ in her practice:

Emotion coaching also “gives you a shared language so that the child and adult are ‘on the same wavelength”, with another practitioner noting “because I now use emotion coaching I think the relationships I have with the children is much more relaxed …allowing greater understanding of each other”. The transferability of emotion coaching skills to other relationships found in educational settings was recognised and one teacher commented “I use the technique mostly with adults, staff and parents and find it very useful in most instances – it provides a people centred consistent and calming approach”.

Other statements that reflect this theme include:

I am able to use it as a tool that helps me connect with more children - that it has helped some of my pupils and helped foster relationships for learning gives weight to the use of the tool.

I let children know that I have an awareness of their emotions more. I also have more constructive conversations about emotions with the children.

It has given me a greater understanding of listening and allowing the child to explain the situation and this can diffuse situations as it allows greater understanding of each other.

It acts as a framework and a script that enables a consistent, positive approach. It empowers staff in dealing with situations because it is a uniform approach.

Theme 2 – Adult Self-regulation (AS)

The key finding from this theme was: Through using emotion coaching, adults found difficult situations less stressful and exhausting with a positive impact on adult well-being.

As a result of emotion coaching training a practitioner stated “It gives both the child and the adult time to think before jumping on the negative behaviour and this allows a calmer, non – confrontational discussion”. The notions that practising emotion coaching “keeps me calm and allows thinking time” and “it keeps you calm because you have something quite simple but effective to use” were common amongst the practitioners. One practitioner reflected “emotion coaching has helped me slow down and think why a child is upset /angry- this often allows the situation to deescalate”. Practitioners recognised changes in their response to emotionally charged situations: “It helps us cool down while we collect our thoughts and I now shout less!”, “I am more patient now “ and “I now focus on emotions as well as the behaviour and give time to validating emotions- it helps us all be reflective about our inner selves”.

Emotion coaching raises awareness of the use of consistent, sensitive communication to promote positive relationships, as one practitioner noted:

Other statements that reflect this theme include:

It makes you stop and think before potentially making a situation worse. It helps you to stay calm - possibly makes you more approachable.

I can remain calm and consistent in my approach, particularly with angry pupils who verbally attack you personally.

I feel I use a more measured and calm approach.

It has helped me have a more consistent response and remain in control of myself as it has given me strategies I can use to diffuse behaviour.

Theme 3 – Behavioural Impact on Child (BIC)

The key finding from this theme was: Emotion coaching promotes children’s self-awareness of their emotions, positive self-regulation of their behaviour and generates nurturing relationships.

A common belief reported was that emotion coaching supports children to calm down and better understand their emotions: “It helps them realise it is Ok to feel sad or angry but that some behavioural responses can be inappropriate- so it gives children tools to help them cope with their feelings”. Practitioners also believe that emotion coaching “enables children to separate themselves from their behaviour- so they don’t label themselves as ‘naughty’ – they just accept that one incident is due to bad choices”. In doing so, it “gives them choices and a way out of a difficult situation without confrontation”. A practitioner noted that he believed “it helps pupils regulate their own behaviour and to deal with them more independently- In the long run it will save you time because the pupils will be able to manage their emotions themselves”.

Adults support self-regulation and facilitate resilience by repeatedly and consistently helping children recognise, regulate, improve and take ownership of their behaviour. A practitioner stated that Another noted that since practising emotion coaching the children By being calmer theyBecause the children

Improved nurturing relationships was another commonly reported impression and evident throughout all 3 identified themes. One participant wrote: “ Another talked about how she considered that emotion. The positive impact on adult-child relationships is also well-illustrated in the following quote:

Other comments that reflect this theme include:

Pupils are better able to self-regulate and understand why they have certain feelings and what to do with them.

They (pupils) feel safe, able to confide, show feelings and know they will be listened to.

We are helping them impact on others positively and guiding them towards self –management.

Evidence of impact from Case Study - Pre- and Post- Training Behaviour Indicator Changes (quantitative)

Possible pre- and post- emotion coaching training changes in pupil behaviour indices (call-outs, exclusions, consequences and rewards) at a secondary school providing education for 1350 pupils were explored. Differences in mean behaviour indices for one academic year pre-training and one academic year post-training were discovered. There was a significant difference in all four behaviour indicators (call-outs, exclusions, consequences and rewards).

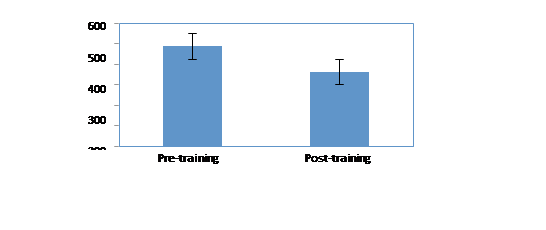

Call-outs

Before professionals were trained in emotion coaching at the school, the mean number of call outs was 487.45 (SD = 254.18) for one year. For one academic year post-training the mean number of call outs was reduced to 363.45 (SD = 194.68). These means are depicted in Figure 4. A paired- samples t-test revealed that this difference was statistically significant (t = 2.35, p < .05). The mean decrease in call-outs was -124 with a 95% confidence interval ranging from 6.65 to 231.35. The eta squared statistic (0.36) indicated a large effect size, with a substantial difference in call-outs pre- and post- training.

Results indicate that emotion coaching may help to reduce the incidents of call-outs.

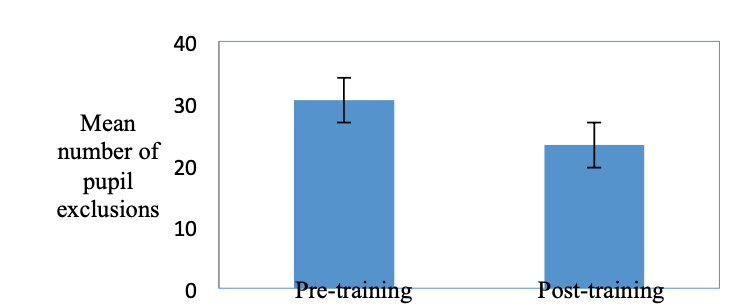

Exclusions

For one academic year pre-training, the mean number of exclusions was 30.82 (SD = 6.07). For the academic year post-training the mean was reduced to 21.55 (SD = 4.06). These means are depicted in Figure 5. A paired-samples t-test revealed that this difference was statistically significant (t = 2.54, p < .05). The mean decrease in exclusions was 8.82 with a 95% confidence interval ranging from 1.14 to 17.40. The eta squared statistic (0.39) indicated a large effect size, with a substantial difference in exclusions pre- and post- training.

Results indicate that emotion coaching may help to reduce the incidents of exclusions.

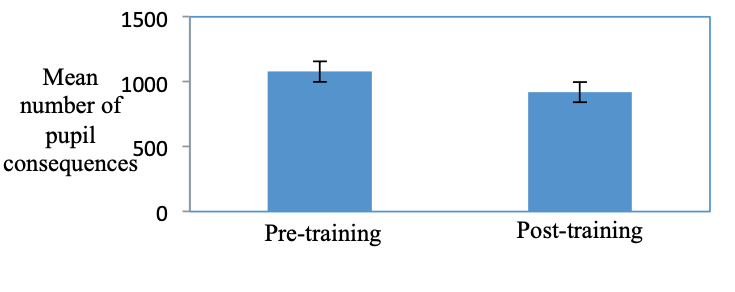

Consequences

The mean number of consequences for one academic year pre-training was 1078.18 (SD = 135.62). For the academic year post-training the mean was reduced to 919.73 (SD = 121.01). These means are depicted in Figure 6. A paired-samples t-test revealed that this difference was statistically significant (t = 2.84, p < .05). The mean decrease in consequences was 158.45 with a 95% confidence interval ranging from 34.04 to 282.87. The eta squared statistic (0.45) indicated a large effect size, with a substantial difference in consequences pre- and post- training.

Results indicate that emotion coaching may help to reduce the incidents of sanctions applied.

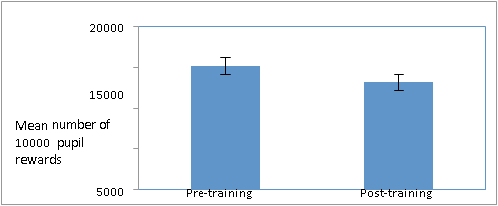

Rewards

For one academic year pre-training the mean number of rewards for pro-social behaviour was 15, 180 (SD = 2426.78). This mean was reduced to 13,158.55 (SD = 2245.79) for one academic year post-training. These means are depicted in Figure 7. A paired-samples t- test revealed that this difference was statistically significant (t = 2.08, p <.05). The mean decrease in rewards was 2022 with a 95% confidence interval ranging from 142.67 to 4186.67. The eta squared statistic (0.30)

Results indicate that emotion coaching may help to reduce the incidents of rewards applied.

Case Study Children

The secondary school selected six young people (four 13 year old boys and two 15 year old girls) who were considered by the staff to be ‘at risk of exclusion’. The ‘team around the child’ were trained in emotion coaching, including the parents. Records were kept of internal exclusions and call outs. A total drop in numbers of internal exclusions – from 21 to 13 - and call outs – from 84 to 36 – (Tables 1-2) was considered by the deputy head of the school to show ‘real improvement’ and reflect the improvements across the school depicted in Figures 4-7.

In addition to the behavioural indices, the research team also interviewed the six case study children (in two groups of 3). The analysed data from these interviews are not recorded in full here, but each of the children interviewed spoke positively about the staff’s usage of emotion coaching. Comments included:

I would, like, walk off, I used to kick off and get excluded again. Now someone tries to, like, calm me down and now I calm down and regret it after. I will go back and say sorry (Girl aged 15)

They listen to you and make sure that you’re OK and, like, trying to make sure you’re stable and stuff and all of this helps you (Girl aged 15)

It calms you down a lot really. If the teachers did that more often that would probably help us, because then we won’t go back in messing around. We’ll be, like all nice and calm. Because if teachers just send us out and just shouts at us we’ll just carry on messing around most of the time. If teachers just asks us how we’re feeling and what happened and everything, we’re going to go in to have the rest of the lesson nice and peaceful and quiet (Boy aged 13)

When people, like, take the mick out of me, like, in class I’d just get angry and I just hit ‘em. Now the teachers talks to me and it calms me down – the other kids don’t really pick on me now because they know that I don’t react (Boy aged 13).

Discussion and Conclusion

Our findings indicate changes in behavioural and socialisation practices consistent with other research on emotion coaching (Katz et al., 2012). Firstly, changes in the participants’ meta-emotion philosophy indicate a reduction in levels of emotion dismissing beliefs by practitioners and more of emotion coaching beliefs and, by implication, an increase in adult self-regulation. This is consistent with other evidence of emotion coaching used for parenting programmes (Gottman et al, 1997, Havighurst et al., 2010, Wilson et al., 2012). Emotion coaching engages with the adult’s beliefs, attitudes, awareness, expression and regulation of emotion, their reactions to children’s expressions and the adult’s discussion and support or coaching of children’s emotions (their meta- emotion philosophy). This corresponds with the evidence identifying the important skills needed to support parental socialization of children’s emotions (Katz et al., 2012). The reported improvements in adult self-regulation during behavioural incidents and enhanced social relationships with children and young people can be linked to other research which highlights the significance of emotional regulation. For example, it is known that practitioners’ emotional response can have a powerful protective influence on performance; and those with stronger emotional regulation are less susceptible to burn out (Bracket et al, 2010; Chang, 2009; Day et al, 2006). Learning and teaching are interpersonal interactions and positive relationships play a key role in productivity and happiness (Yano, 2013).

Secondly, our findings reveal a reduction in disruptive behaviour and a positive impact on behavioural regulation (improved pro-social behaviour) by the children/young people across the settings. This concurs with successful usage of emotion coaching in reducing externalising behaviour (Havighurst et al., 2013; Katz & Windecker-Nelson, 2004). One particularly interesting finding was the reduction in the use of sanctions and rewards in the secondary school case study. Since emotion coaching is offered as an alternative paradigm, by focusing attention on the feelings underlying behaviour rather than behaviour modification, our research suggests that a more relational model can reduce the need for rewards and sanctions in supporting behaviour. It also implies that emotion coaching can be utilised successfully alongside (or at least as a supplement to) the existing behaviourist model endorsed by the English government as highlighted in our introduction (DfE, 2011b, DfE, 2012a). The common participant claims of how emotion coaching helps to generate a more consistent response to behavioural incidents resonates with literature highlighting the important of consistent responsiveness in promoting social and cognitive growth (for example, Landry et al, 2001).

Thirdly, results suggest that emotion coaching appears to promote the development of social and emotional competences within children/young people, as well as encourage more humanist and affective relationships (Shaughnessy, 2012; van der Hoeven et al., 2011) between practitioners and pupils, since it rests on the premise that understanding should precede advice i.e. ‘rapport before reason’ (Riley, 2010). Wilson et al (2012) emphasise that emotion coaching differs from other traditional parenting practices which do not first respond to the child’s emotional state before problem-solving or disciplining. The frequent descriptions by participants of the way in which emotion coaching de-escalates incidents and helps both the children/young people and adults to ‘calm down’ suggests improvements in the stress response system as reported by Gottman et al.’s (1997) emotion coaching research, and reflects how children/young people (and adults) felt more able to regulate their emotional responses. The narrative provided by emotion coaching creates a communicative context for a child’s emotional experiences to be explicitly and meaningfully processed within a relational dyad, and resonates with Siegel’s work on interpersonal neurobiology (Siegel, 2010, 2012). Katz et al identify that emotion coaching embraces ‘three key aspects of children’s emotional competence: emotional awareness, expression and regulation’ improving children’s psycho-social adjustment and peer relations (2012, p. 418). This is reiterated by Havighurst et al.’s (2013) review of the literature on emotional competence which comprises skill development in the knowledge, understanding and communication of self and others’ emotions, alongside the capacity to modulate affect expression in socio-culturally appropriate ways. The affective teacher behaviours of warmth and empathy are strongly associated with positive school outcomes (Cornelius-White, 2007) and, as noted in our introduction, skills in emotional regulation have significant educational and social effects (Durlak et al, 2011, MacCann, 2010; Weare & Gray, 2003).

Limitations of the study include its relatively small size, lack of demographic data and a sample limited in terms of cross-cultural and socio-economic representation. No observational data of actual incidents when emotion coaching was used by participants were recorded. Most of the data sets relied on subjective self-reporting (Ogden, 2012) and were therefore subject to expectancy and social desirability bias (Coolican, 2009). Accurate measures of the ‘effect’ of emotion coaching on individual emotional and behavioural well-being can only be surmised as it is impossible to exclude confounding and extraneous variables. Inconsistent attendance at all training and network/booster meetings, due to other commitments and responsibilities, meant that for some participants their level of engagement and understanding of the project may have diminished.

The pilot study did not explore the moderating role of developmental stages or age. There is little research on how the component processes of emotion coaching ought to be accommodated for different developmental ages and stages. For example, Katz et al note (2012) that acceptance of emotions may have more significance with adolescents than awareness or direct coaching, whilst younger children are more susceptible to emotion dismissing and require more explicit labelling, role-modelling and coaching. Our evidence reveals that emotion coaching can be successfully applied to all age groups (0-16 years), with the necessary adaptations being made by practitioners largely experienced in differentiating children and young people’s learning; although practitioners in the secondary schools considered that care had to be taken not to appear patronising when using the emotion coaching narrative. Katz et al also note that ‘some children, whether because of temperament or physiological regulatory abilities, may be more amenable to emotion coaching than others (2012: 421)’.

Whilst we are mindful of critics of so-called deficit models of ‘therapeutic education’ such as Eccelstone et al. (2005) and Gillies (2011), or those who urge caution in applying such techniques in practice (Mayer and Cobb, 2000), emotion coaching is nonetheless offered as a valuable tool for practitioners in their work with children and young people. The evidence suggests that emotion coaching can be used to generate a community-wide, consistent approach to supporting young children's behaviour. It provides a contextual model for promoting empathetic responses and thought constructions that support behavioural self-management in young children. It promotes nurturing and emotionally supportive relationships which can provide optimal contexts for the promotion of resilience and sustainable futures. Some challenges to implementation were identified, the most common of which is lack of sufficient time to apply the processes of emotion coaching in some contexts, particularly when competing with the demands of large numbers of children in a classroom and a busy curriculum. Nonetheless, emotion coaching provides professionals with a relational model to support their work and teaches more empathic ways to manage behaviour and engender resilience and confidence, rather than relying only on traditional behaviourist principles of sanctions and rewards.

Further research is needed to verify our findings, including RCTs. Since the bulk of the data from this project was drawn largely from school contexts and education staff, further investigation is needed within other community settings such as early years and youth centres, as well as with other professionals such as health visitors, social workers and youth workers. A wider cross- cultural and socio-economic evidence base is also needed. Nonetheless, the evidence of the transferability of emotion coaching to these wider contexts has revealed promising results (Rose et al, forthcoming; Gilbert et al, 2014; Rose et al, 2012).

Acknowledgements

This project was funded by the Sharing Knowledge, Shaping Practice Partnership Fund at Bath Spa University and two Wiltshire Council Local Area Boards. Our thanks go to the funding bodies and to all the participants in the project for their willingness, time and effort in implementing emotion coaching techniques into their work with children and young people.

References

Ahn, H., & Stifter, C. (2006). Childcare teachers’ response to children’s emotional expression, Early Education and Development, 17.2, 253-270. DOI:

Boyd, J., Barnett, W., Bodrova, E., Leong, D., Gomby, D., Robin, K., & Hustedt, J. (2005). Promoting Children’s Social and Emotional Development through Preschool, NIEER Policy Report, New Brunswick, New Jersey: National Institute for Early Education Research, Rutgers University.

Brackett, M., Palomera, R., Mojsa-kaja, J., Reyes, M., & Salovey, P. (2010) Emotion regulation ability, burnout and job satisfaction amongst secondary-school teachers, Psychology in Schools, 47.4, 406- 417. DOI:

British Psychological Society (2011). British Psychological Society Code of Ethics. Leicester: British Psychological Society.

BSU (2011). Research Ethics Regulations. Bath: School of Education Research Ethics Committee, Bath: Bath Spa University.

Chang, M. (2009). An appraisal perspective of teacher burnout: examining the emotional work of teachers, Educational Psychology Review, 21,193-218. DOI:

Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis. London: Sage.

Chen, F. M., Hsiao, S. L., & Chun, H. L. (2011) .The role of emotion in parent-child relationships: Children’s emotionality, maternal meta-emotion, and children’s attachment security. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 21, 403-410. DOI:

Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2007). Research Methods in Education. Abingdon: Routledge. Coolican, H. (2009) Research Methods and Statistics in Psychology. London: Hodder. DOI:

Cornelius-White, J. (2007). Learner-centered teacher–student relationships are effective: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 77, 113–143. DOI:

Creswell, J. (2002). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. 2nd ed. London: Sage.

Cunningham, J. N., Kliewer, W., & Garnder, P. W. (2009). Emotion socialization, child emotion understanding and regulation, and adjustment in urban African American families: Differential associations across child gender. Development and Psychopathology, 21, 261-283. DOI:

Davis, H.A. (2003). Conceptualizing the role and influence of student–teacher relationships on children’s social and cognitive development. Educational Psychologist, 38(4), 207–234. DOI:

Day, C., Kington, A., Stobart, G., & Sammons, P. (2006). The personal and professional selves of teachers: stable and unstable identities, British Educational Research Journal, 32.4, 601–616. DOI:

Denscombe, M. (2010). The good research guide for small scale social research projects. 4th ed. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

DfE (2011a). Parenting Early Intervention Programme Evaluation Research Report 121. London: DfE.

DfE (2011b) The Education Act. London: DfE.

DfE (2012a) Ensuring Good Behaviour in Schools: A Summary for Heads, Governing Bodies, Teachers, Parents and Pupils. London: DfE.

DfE (2012b) Teachers’ Standards. London: DfE.

DfES (2004) Every Child Matters: Change for Children. London: DfES.

Dunsmore, J. C., Booker, J. A., & Ollendick, T. H. (2012). Parental emotion coaching and child emotion regulation as protective factors for children with oppositional defiant disorder. Social Development, 22, 444–466. DOI:

Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., & Schellinger, K. B. (2011). The Impact of Enhancing Students’ Social and Emotional Learning: A Meta-Analysis of School-Based Universal Interventions, Child Development, 82:1, 405–432. DOI:

Ecclestone, K., Hayes, D., & Furedi, F. (2005). Knowing me, knowing you: the rise of therapeutic professionalism in the education of adults. Studies in the Education of Adults. 37.2, 182-200. DOI:

Ellis, B. H., Alisic, E., Reiss, A., Dishion, T., & Fisher, P. A. (2014). Emotion Regulation Among Preschoolers on a Continuum of Risk: The Role of Maternal Emotion Coaching. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 23, 965–974. DOI:

Elliot, J. (1991). Action Research for Educational Change. Buckingham: Open UP.

Ferguson, G., & Takane, Y. (1989) Statistical Analysis in Psychology and Education, McGraw-Hill, New York.

Freiler, T. (2008). Learning through the body. In New directions for Adult and Continuing Education: no. 119, ed. S. Merriam, 37-48. San Francisco: Jossey- Bass, Wiley Co. DOI:

Fullan, M. (2007). The New Meaning of Educational Change. London: Routledge.

Gilbert, L. (forthcoming). The transference of Emotion Coaching into Community and Educational Settings, the Practitioners’ Perspective Unpublished Doctoral Thesis. Bath: Bath Spa University.

Gilbert, L., Rose, J., & McGuire-Sniekus, R. (2014). In Thomas, M. (ed) Promoting children’s well-being and sustainable citizenship through emotion coaching A Child’s World: Working together for a better future. Aberystwyth: Aberystwyth Press.

Gillies, V. (2011). Social and emotional pedagogies: critiquing the new orthodoxy of emotion in classroom behaviour management. British Journal of Sociology of Education. 32 (2) 185-202. DOI:

Goswami, U. (2011). Cognitive neuroscience and learning and development. In Moyles, J., Georgeson, J. and Payler, J. (eds.) Beginning Teaching Beginning Learning in Early Years and Primary Education. Maidenhead: Open UP.

Gottman, J., Katz, L & Hooven, C. (1996), Parental meta-emotion philosophy and the emotional life of families: Theoretical models and preliminary data, Journal of Family Psychology, 10.3, 243-268. DOI:

Gottman, J., Katz, L., & Hooven, C. (1997). Meta- Emotion –how families communicate emotionally, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Graziano, P. A., Reavis, R. D., Keane, S. P., & Calkins, S. D. (2007). Emotion Regulation and Children's Early Academic Success. Journal of School Psychology, 45.1, 3-19. DOI:

Gross, J. (2013). Emotion regulation: taking stock and moving forward. American Psychological Association, 13.3, 359-365. DOI:

Havighurst, S. S., Wilson, K. R., Harley, A. E., Prior, M. R., & Kehoe, C. (2010). Tuning into Kids: Improving emotion socialization practices in parents of preschool children—findings from a community trial. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 51, 1342-1350. DOI:

Heckman, J., Stixrud, J., & Urzua, S. (2006). The effects of cognitive and non-cognitive abilities on labor market outcomes and social behaviour, Journal of Labor Economic, 24, 3, 411-482. DOI:

Havighurst, S. S., Wilson, K. R., Harley, A. E., Kehoe, C., Efron, D., & Prior, M. R. (2013). ‘‘Tuning into Kids’’: Reducing Young Children’s Behavior Problems Using an Emotion Coaching Parenting Program. Journal of Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 44.2, 247-264. DOI:

Hutchings, J., Martin-Forbes, Pm, Daley, D., & Williams M. E. (2013). A randomized controlled trial of the impact of a teacher classroom management program on the classroom behaviour of children with and without behavior problems. Journal of School Psychology, 51, 571–585. DOI:

Immordino-Yang, M., & Damasio, A. (2007). We feel, therefore we learn: The relevance of affective and social neuroscience to education. Mind, Brain and Education Journal, 1.1, 3-10. DOI:

Jakhelln, R. (2010). Early career teachers’ emotional experiences and development, a Norwegian case study. Professional Development in Education, 37.2, 275-290. DOI:

Johnson, B., & Christensen, L. B. (2012). Educational Research: Quantitative, Qualitative and Mixed Approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA.: Sage.

Katz, L. F., & Hunter, E. C. (2007). Maternal meta-emotion philosophy and adolescent depressive symptomatology. Social Development, 16, 343–360. DOI:

Katz, L. F., & Windecker-Nelson, B. (2004). Parental meta-emotion philosophy in families with conduct- problem children: Links with peer relations. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 32.4, 385-98. DOI:

Katz, L. F., Hunter, E., & Klowden, A. (2008). Intimate partner violence and children’s reaction to peer provocation; The moderating role of emotion coaching. Journal of Family Psychology, 22.4, 614-21. DOI:

Katz, L. F., Maliken, A. C., & Stettler, N. M. (2012). Parental meta-emotion philosophy: A review of research and theoretical framework. Child Development Perspectives, 6.4, 417-422. DOI:

Landry, S. H., Smith, K. E., Swank, P. R., Assel, M. A., & Vellet, S. (2001). Does early responsive parenting have a special importance for children’s development or is consistency across early childhood necessary?. Developmental Psychology, 37.3, 387-403. DOI:

Lagace-Seguin, D. G., & Coplan, R. J. (2005). Maternal emotional styles and child social adjustment: Assessment, correlates, outcomes and goodness of fit in early childhood, Social Development, 14.4, 613- 636. DOI:

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic Inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. DOI:

Linnenbrink-Garcia, L., & Pekrun, R. (2011) Students’ emotions and academic engagement: Introduction to the special issue. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 36, 1–3. DOI:

MacCann, C., Fogarty, G. J., Zeidner, M., & Roberts, R. D. (2010). Coping mediates the relationship between emotional intelligence (EI) and academic achievement. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 36.1, 60–70. DOI:

Mayer, J., & Cobb, C. (2000). Educational Policy on Emotional Intelligence: Does It Make Sense? Educational Psychology Review, 12.2, 163-183. DOI:

McGuire-Sniekus, R., Rose, J., & Gilbert, L. (forthcoming) A new scale to assess meta-emotion philosophy for the use of emotion coaching in professional context. European Journal of Psychology of Education.

Murphy, J., Havighurst, S., & Kehoe, C. (forthcoming) ‘Trauma-focused Tuning in to Kids’, Journal of Traumatic Stress.

Nias, J. (1996). Thinking about feeling, the emotions in teaching, Cambridge Journal of Education, 26.3, 293– 306. DOI:

Ogden, J. (2012). Health Psychology. Maidenhead: Open UP.

OFSTED (2013) Not yet good enough: personal, social, health and economic education in schools [online]. Available at: http://www.ofsted.gov.uk/resources/not-yet-good-enough-personal-social-health-and- economic-education-schools (accessed 21/01/ 2014).

Riessman, C. (2008). Narrative Methods for the Human Sciences. London: Sage.

Riley, P. (2010). Attachment Theory and the Teacher Student relationships. London: Routledge. DOI:

Rose, J., Gilbert, L., & Smith, H. (2012). Emotion coaching: a new approach to support and promote sustainable emotional and behavioural well-being through the adoption of emotion coaching techniques into community-wide professional and parental practice. Conference paper EECERA, Portugal.

Rose, J. Gilbert, L., & McGuire-Sniekus, R. (forthcoming) Supporting children and young people’s awareness of their emotional and behavioural self-regulation through emotion coaching. Journal of Pastoral Care and Education.

Shortt, J. W., Stoolmiller, M, Smith-Shine, J. N., Eddy, J. M., & Sheeber, L. (2010). Maternal emotion coaching, adolescent anger regulation, and siblings’ externalizing symptons. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 51.7, 799-808. DOI:

Shaughnessy, J. (2012). The challenge for English schools in responding to current debates on behaviour and violence, Pastoral Care in Education: An International Journal of Personal, Social and Emotional Development, 30(2), 87-97. DOI:

Siegel, D. J. (2010). Mindsight: The New Science of Personal Transformation. New York: Bantam/Random House.

Siegel, D. J. (2012). The Developing Mind: How Relationships and the Brain Interact to Shape Who We Are. London: Guildford Press.

Shipman, K. L., Schneider, R., Fitzgerald, M. M., Sims, C., Swisher, L., & Edwards, A. (2007). Maternal emotion socialization in maltreating and non-maltreating families: Implications for children's ER. Social Development, 16, 268-285. DOI:

Skinner, B. F. (1968). The Technology of Teaching. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques.Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Sutton, R., Mudrey-Camino, R., & Knight, C. (2009). Teachers’ emotion regulation and classroom management, Theory into Practice, 48,130-137. DOI:

Tucker, C. M., Zayco, R. A., Herman, K. C., Reinke, W. M., Trujillo, M., & Carraway, K. (2002). Teacher and child variables as predictors of academic engagement among low-income African American children. Psychology in the Schools, 39, 477–488. DOI:

van der Hoeven Kraft, K, J., Srogi, L., Husman, J., Semken, S., & Fuhrman, M. (2011). Engaging Students to Learn Through the Affective Domain: A new Framework for Teaching in the Geosciences. Journal of Geoscience Education, 59, 71-8. DOI:

Weare, K., & Gray, G. (2003). What Works in Developing Children’s Emotional and Social Competence and Wellbeing? Nottingham: DfES.

Webster-Stratton, C., & Reid, M. J. (2004) Strengthening Social and Emotional Competence in Young Children - The Foundation for Early School Readiness and Success. Infants and Young Children, 17.2, 96-113. DOI:

Wilson, K. R., Havighurst, S. S., & Harley, A. E. (2012). Tuning into Kids: An effectiveness trial of a parenting program targeting emotion socialization of preschoolers. Journal of Family Psychology, 26.1, 56-65. DOI:

Wilson, B. J., Berg, J. L., Surawski, M. E., & King, K. K. (2013). Autism and externalizing behaviours: Buffering effects of parental emotion coaching. Research in Austism Spectrum Disorders, 7, 767-776. DOI:

Yano, K. (2013). The science of human interaction and teaching, Mind, Brain and Education, 7(1), 19-29. DOI:

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.