Abstract

This present study investigates in-service EFL Vietnamese teachers’ responses to the government language proficiency requirements imposed on them. The study adopts a language proficiency self-assessment survey and semi-structured interviews with respectively 350 and 44 participants. The data analysis generates a matrix of interrelated challenges underlying the teachers’ dilemma in the participant’s English proficiency development. The interwoven challenges demand for a holistic approach with better collaboration among different forces across levels to draft meaningful and long term supporting plans in this context. The analysis also shows the participants all longed for a more appropriate support framework to improve their English language proficiency while acknowledging they are competent to execute their teaching practices.

Keywords: On-native, language proficiency, EFL teachers, language policy

Introduction

English rose to the status of the most popular foreign language in Vietnam as early as 1990s. However, it was not until 2003 that English was officially included as an optional subject to be taught in primary education. In 2008, English was officially institutionalized in the primary education system with the projection that by 2018, 100% of students should be taught English (Vietnamese Government, 2008). In 2008, the nation-wide project 2020 was approved as the government’s and MOET’s latest attempt to promote English learning (Vietnamese Government, 2008). The planned outcome was to have students graduating from primary (6-10 years old), lower secondary (11-15 years old) and upper secondary (15-18 years old) schools reaching levels A1, A2, and B1 respectively of the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment (CEFR). For undergraduate education, the target was set at level B1, B2, and C1 for graduates from, respectively, institutions not specializing in foreign languages, college (2 year) and university (4 year) programs with a specialization in foreign languages.

Problem Statement

The rising need for English language learning reveals severe problems, including teachers’ low language proficiency and inappropriate training. Limited studies at primary school level by scholars such as Nguyen (2011) and Le and Do (2012) revealed that teachers were not sufficiently prepared to teach English at the elementary level due to their weaknesses in pedagogical skills, vocabulary knowledge and pronunciation. These weaknesses were attributed to low-quality pre-service training, the lack of an environment for language use and practice, and isolation from the professional community. They called for intensive retraining of current in-service primary teachers regarding both language competence and language teaching methodology. Teachers need to be equipped with background knowledge of theories and methods of teaching English to young learners while priority should be put on the improvement of teachers’ pronunciation and fluency. Attempts should also be made to establish communities of practice (Wenger, 1998) to promote teachers’ self-engagement in the continuous development of knowledge and skills.

Discussing the teaching of English in Vietnam in general, Le (2007) specified the lack of well- trained teachers as one of the three inherent problems accounting for the low quality of foreign language education in Vietnam. Indeed, questions have been raised concerning the ability of in- service teachers and the quality of pre-service teacher training programs. The media reported the shocking results of a nation-wide teachers’ language proficiency assessment test in which, even in big cities like Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh, only a fifth of those tested qualified for the CEFR’s B2 level of language proficiency. In one particular province, Ben Tre, only one teacher out of 700 tested passed this threshold level. Officials from MOET and project 2020 reported that 80 000 in- service teachers needed further training as 97%, 93%, and 98% of teachers at primary, lower secondary, and upper secondary respectively were underqualified (Nguyen & Dudzik, 2013). Criticisms were made, and plans were carried out to “standardize” teachers’ language proficiency. However, what is missing from all these discouraging statistics and nationwide supporting programs is an account of teachers’ own perception of their language proficiency and the kind of training and support they need. Do these teachers perceive that they need to improve their language proficiency? How they maintain and develop it? What are the challenges they face? What kind of training and support do they expect? All these questions were left unanswered. As the teachers are at the center of this language policy, it is crucial that their voices are heard so their needs can be catered for.

The issue of non-native English speaking teachers’ (NNESTs) language proficiency development is often emphasized in the literature. Farrell and Richards (2007) dedicated a whole chapter to the issue of language proficiency as the fundamental component of language teachers’ professional competence. It even has been stated that NNESTs’ most important professional duty is to make improvements to their English (Medgyes, 2001). Alarmingly, the literature has plenty of evidence concerning NNESTs’ alarmingly low levels of proficiency. Nunan (2003) found that the English proficiency of many teachers in several EFL contexts (China, Hong Kong, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, Taiwan, and Vietnam) was insufficient to provide learners with rich input needed for successful language acquisition. Butler (2004) and Tang (2007) found that teachers in Korea, Taiwan, Japan, and China perceived their proficiency levels to be lower than the minimum levels they considered necessary to teach English. Researchers like Nunan (2003), Butler (2004) and Tang (2007) all argued for an urgent improvement of NNSTs’ language proficiency. While native-like pronunciation or intonation might not be necessary, NNESTs need a sufficient mastery of English to be effective, self-confident, and satisfied professionals (Crystal, 1998; Davies, 1991). In order for such mastery to be achieved, it is of utmost importance that language practice and learning are considered part of a continuing process throughout the NNEST’s career (Braine, 2010; Medgyes, 1994, 2001). Once language learning is accepted as never complete, NNESTs should be considered lifelong learners with all the difficulties, anxiety and needs typical of language learners.

Unfortunately, the current literature suggests that in-service foreign language teacher education programs do not offer many opportunities for language teachers to maintain or improve their language skills. The language proficiency development of these NNESTs is often taken for granted. Undergraduate and postgraduate TESOL programs often do not formally teach speaking and listening since they tend to assume that their teacher trainees already have a satisfactory proficiency level (Pasternak & Bailey, 2004, p. 166). Medgyes (1999) commented that language training is ignored in many TESOL programs and gave the example of his own Center for English Teacher Training at the Evotvos Lorand University in Budapest. Medgyes is not the only one who has emphasized the importance of language training for language teachers. Further researchers have documented in-service teachers’ difficulties in maintaining their language proficiency when confined to teaching lower-level classes for a long period of time, and teachers’ discontent with their teacher training programs (e.g. Cooper, 2004; Fraga-Canadas, 2010; Schulz, 2000).

To sum up, studies concerning NNESTs’ language proficiency often reveal teachers’ less-than- desirable levels of language proficiency and their wish to improve their current levels but fail to document the actual strategies employed and the difficulties encountered. Therefore, this study seeks to investigate the participants’ (Vietnamese teachers of English) perceptions of their own language proficiency and attitudes towards language proficiency development including the difficulties they encounter during this process.

Research Questions

The research questions therefore are as follows:

(1) What are the participants’ perceptions of their own language proficiency?

(2) What are the challenges to participants’ language proficiency development?

Purpose of The Study

The present paper investigates in-service language teachers’ responses to the Vietnamese Ministry of Education and Training, MOET’s established language proficiency standard during a training course organized as part of national project 2020 to improve the quality of English language teaching and learning. To the end, the paper first presents a comparison of Vietnamese NNESTs’ perceived language proficiency (LP) with their perceived required language proficiency (RLP) to teach effectively at their working level. It then focuses on one case to demonstrate a matrix of challenges to teachers’ professional development in Vietnam. The paper responds to a real-life situation and emphasizes the need to consider teachers’ voices when developing and implementing high-stake policy.

Research Methods

The present study employed a language proficiency self-assessment survey and semi-structured interviews in Vietnamese with in-service teachers. It compared the language teachers’ perceived language proficiency (LP) and perceived level of language proficiency required for their job (RLP). The survey was based on the self-assessment grid from the CEFR which MOET had adopted. The 6 levels (from A1 to C2) of the CEFR were converted to a 6 point scale (Level A1 was given 1 point, A2 2 points and so on). It was also possible for the participants to rate their proficiency between levels (e.g., between B1 and B2 at 3.5 or between B2 and C1 at 4.5). The data were not used as indicative of participants’ actual language proficiency but only provided information to test the hypothesis that there a gap existed between the self-assessed and the perceived required level of English proficiency. It was hypothesized that such a gap might fuel language learning as it would reveal participants’ perceived strengths and weaknesses in language proficiency. This hypothesis is based on the results of a similar study conducted with primary teachers in other Asian contexts (Butler, 2004). Another aim, achieved through the interviews, was to investigate participants’ difficulties during language maintenance and improvement.

350 teachers completed the self-assessed language proficiency survey. These in-service teachers were working in four Northern provinces in Vietnam. They were recruited for the survey on a voluntary basis during their participation in a training course at four training locations. This course was organized by MOET as part of the national project 2020. The purpose of the course was to improve teachers’ language proficiency and prepare for a standardization test.

Semi-structured interviews were then conducted in Vietnamese with 44 participants recruited on a voluntary basis. Five of the 44 participants then participated in several in-depth and repeated interviews over a 10 week period. The interview questions concerned the teachers’ teaching contexts (institution, workload, colleagues, students, professional development activities), attitudes towards and strategies related to language proficiency maintenance, personal and professional difficulties which hindered language proficiency development, attitudes towards MOET’s training courses and standardized levels of language proficiency, opinions regarding the practicality of the courses and suggestions for improvement of pre- and in-service teacher training courses. Participants’ responses were then analysed for common themes with regards to the research aims. The results of this analysis are presented below.

Findings

Participants’ perceptions of their own language proficiency

The survey results revealed that Vietnamese school teachers rated their language proficiency (on all skills) higher than that which, in their opinion, was required for their job. The average self- rated LP was 2.73 (less than B1 or 3 points), higher than their average perceived RLP of 2.35. This was much lower than the B2 (or 4 points) standard set by MOET. In fact, the perceived RLP was consistently low across all skills with the lowest (Listening) being 2.15 (just around than A2 at 2 points). The following table summarizes the results of the survey.

The results are in stark contrast with those reported in similar contexts by Butler (2004). Butler (2004) surveyed teachers in Korea, Taiwan and Japan to compare their perceived oral proficiency, reading comprehension, and writing ability with the perceived level of proficiency required for successful English teaching at primary level. She found that teachers in all three countries self- assessed their English language proficiency substantially lower than the required level (LPs were lower than RLPs) and argued that such gaps constitute teachers’ motivation for language improvement. The results of this current study in the Vietnamese context also found a gap between LPs and RLPs, but LPs were higher than RLPs in all five categories of language proficiency.

While the gap between LPs and RLPs suggest teachers’ confidence to teach, this should not be interpreted as meaning teachers lack motivation for language proficiency improvement. In fact, the interview revealed teachers’ thirst for knowledge and longing for support to improve language proficiency. The following section will discuss the participants’ attitudes towards their language proficiency, strategies to maintain and develop it and their need of support and training.

Participants’ attitudes towards language proficiency development

Participants’ dissatisfaction with their low level of language proficiency

Despite the participants’ general confidence that their language proficiency was enough for their job, many participants voiced discontent at their low level of language proficiency as expressed in the following quotes:

For my job, [my language proficiency] satisfies the requirements. For myself, no [it doesn’t satisfy me] as I always want to improve.

If not for this course, I was quite satisfied [with my language proficiency] as I am a key figure in the whole district. Yet after [joining] this course, I realize that Oh my [language proficiency] is just of middling level. Well, [it is] truly is.

I think I am good enough to teach my students… Satisfied? In fact I am really not satisfied [with my language proficiency]. I have just changed from teaching French to teaching English. You know, it is hard.

It is worth pointing out that in Vietnam, for many primary teachers, maintaining their language proficiency let alone improving it after graduating from teacher training program is already a huge challenge. This is especially true if the teachers have been required to teach at low level for a long time. Teachers in Vietnam often work at one school, and teach at one level for a long time, even for their whole career as there is no policy of teacher rotation. Job-hopping is generally not encouraged, especially as teaching is long considered a stable and secure job. Participants often use the metaphors of “getting lost” or “rusting away” to describe the weakening of their language proficiency after teaching at primary level for some years.

Strategies to develop language proficiency

The interviewed teachers employed different strategies to develop language proficiency which can be categorized in two major groups, namely individual and social strategies. The individual strategies consist of practicing reading and listening skills via the Internet or 3G mobile network or via watching TV and radio programs, using more traditional learning aids such as books and sample tests and highly individual methods of language practice including reciting monologues while commuting to work or in front of a mirror. Interestingly, although Web 2.0 technologies have allowed and encouraged collaboration and interaction among internet users, none of the participants mentioned such interactive features. They seem to make use of the Internet only as a source of materials rather than a virtual environment which could facilitate language use. Frequently cited websites such as http://www.britishcouncil.vn/ and http://www.tienganh123.com/ were highly appreciated for their resources rather than as a means to connect with colleagues or experts in ELT. From the data, it is not clear whether this is due to the participants’ lack of awareness of such features or their unwillingness to employ them. Still the result is teachers’ isolation from the professional community as reported by Le & Do (2012).

The social strategies comprise practicing the language via teaching, participating in professional development activities such as teaching competitions, classroom observation and teacher group discussion, and doing part-time language-related jobs or pursuing further education for degrees or certificates related to language teaching. Some social strategies were officially required by the school while others were initiated by the teachers themselves. Interestingly, most participants admitted that compulsory strategies (participating in teaching competitions, classroom observation and teacher group discussion) only generated limited help for their language proficiency development despite being highly time-consuming. The participants, therefore, turned to other strategies namely practicing using the language via teaching, doing part-time jobs which required using English, and pursuing further education taught in English.

What is worth noticing is participants’ heavy dependency on individual strategies to maintain and develop language proficiency. In order to create professional communities both online and off- line which are friendlier and more approachable to more teachers it is essential that changes be made to promote the use of social strategies and improve their effectiveness.

The need for support and training programs

Despite the participants’ seeming confidence that they are qualified to teach, the semi-structured interview data reveal their thirst for knowledge and long-term supporting programs. Participants often expressed their happiness at getting a chance to join the training course. The following quotes illustrate such positive feelings:

…studying here is like having meals every day. I feel it [knowledge] gradually permeate me. There are many things which have confused me during my 10 years’ experience of teaching, but I have no one to ask, no source from which to seek answers. The internet can only provide partial and unverifiable solutions.

I myself really want to improve. After this training course, I really like studying. I always want to study.

For me, as my life is stable and secure now, I really want to study to improve my English. I mean grammatical knowledge alone is not enough. I want to be able to speak English well and listen well. I want to study further. Yet few opportunities are available.

The participants’ thirst for knowledge and yearning for support explain their enthusiasm to join the training course. This kind of training with a focus on language proficiency is the first of its kind as it was organized after the teachers’ poor performance on the standard test as reported earlier. Previously, training was often organized with a focus on language teaching methodology. Yet even such training was infrequent and unreachable for most teachers as documented in the literature (see Grassick, 2006; Hayes, 2008; Moon, 2009; Nguyen, 2011).

So far the data have revealed a paradox experienced by most of the participants. On the one hand, the participants were confident that they were qualified to teach English at primary level despite their low language proficiency. This could be explained by their perception of teaching English at primary and secondary school as simple and mainly composed of introducing simple vocabulary and structures. On the other hand, despite such confidence, the participants expressed their unease and dissatisfaction with their own language proficiency which were revealed in their thirst for knowledge and longing for support. This explains the fact that despite the inappropriate content of the training course which mostly could not be applied in their daily teaching, the participants still enjoyed it as a chance to revise what they had learned during their undergraduate study, to get introduced to CEFR’s B2 level materials, and to practice the language.

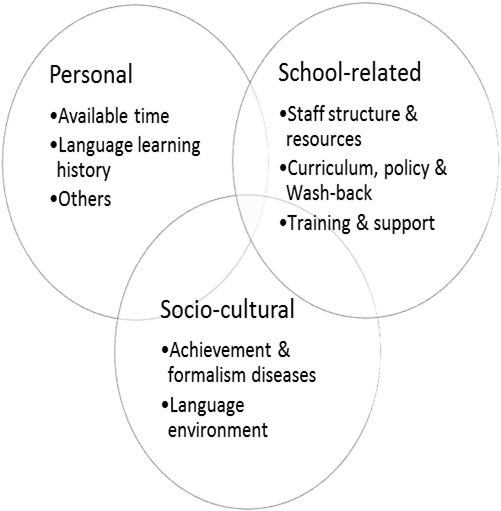

What is more important than such contradiction is the participants’ overwhelming sense of helplessness while confronted by the various challenges to their language proficiency maintenance and improvement. It is this matrix of interrelated difficulties which inhibits teachers’ language proficiency maintenance and improvement. These problems could be broadly categorized, as in the following figure, into three categories, namely personal, school-related and sociocultural challenges. It is of utmost important to understand and resolve these problems in order to provide adequate training and support.

While these three categories and their interplay will be exemplified in much greater detail in another paper, it is important to highlight that the borderline between these categories is blurry as they are inextricably interwoven and overlap. The following part will briefly present one case (out of the five in-depth interviews) to illustrate these interactions and overlap.

Case: Na – from a reluctant to passionate English teacher

Formally trained as a translator, Na had no plan to work as an English teacher. After graduation, she worked for one year at a foreign owned company. After eight years of learning English, this was the first time she used English in real life with foreigners. A year later, in 1999, got married and moved to Hanoi where she worked casually at a private secondary school. She was not happy with the job switch, mainly due to financial-related reasons and her lack of training in language education. Teaching, for her, was a low paid but stable job with much free time. In late 2000, Na applied for a permanent teaching position (long-term contract-based position) at a public school. The stability of the job, and the school’s convenient location were the main reasons for her application. She faced the process with a relaxing attitude and unexpectedly won the position. She considered the success as an epiphany and committed more time and efforts to teaching. Five years later, she was the first English teacher in her school with a Master degree. She felt the pressure but also honour and inspirations to keep pushing ahead. In 2011, Na won a government scholarship for doctoral study in Australia. However, she turned down the offer due to family reasons. Now she described herself as a professional English teacher and was preparing to offer new courses to tutor IELTS and TOEFL students.

narrative partly illustrates the difficulties permeating all three circles of challenges. At personal level, in the beginning of her career, Na was struggling financially to make ends meet. She was not happy with the job switch, mainly due to financial-related reasons. In her own words,

… my salary was much higher. Now, I have to make do with a scanty amount, even not enough for me to go out regularly to maintain relationship with my colleagues. I was very disappointed.

Consequently, Na had to have a second job. She started an on-line business selling clothes which was quite successful. However, managing the business was time-consuming and it took away her time for professional development. Financial difficulty is common in the Vietnamese context, as a result of inappropriate governmental policy. Typically, a newly graduated teacher earn less than US100$ monthly, far from enough to cover their daily expenses, especially in expensive area like Hanoi. Other interviewed teachers also reported the same problem. One desperate teacher similarly complained:

I cannot hang out with friends, and colleagues. Everything is too expensive. I have to save money for my family. I cannot join any professional network, community group, and even lose contact with old friends. It is very depressing.

Hence, an inadequate salary policy at the socio-cultural level can negatively influence the building and maintaining of professional community at the school-related level, and teachers’ limited time for professional development at the personal level. As the proverb goes, a hungry belly has no ears, it is unsurprising that poorly paid teachers need to divert their attention and dedication to feed their empty stomach.

Another example is the powerful influence of wash-back effects at the school-related level on teachers’ language learning history at the personal level and achievement disease at the socio- cultural level.s language learning history, similar with those of many other interviewed participants, was highly characterized with strong emphasis on grammar and reading. This is the consequence of deeply-rooted high-stake exams. As paper-based tests, designed to test only grammatical knowledge, are still popular as clearly manifested in the lack of listening and speaking components in many examinations, including the high-stake university entrance and graduation examinations, was forced to drill students the same way she was drilled for these tests and neglect the development of communicative competence. At the higher level, socio-cultural level, this challenge manifested itself as a negative phenomenon known as ‘excessive craves for achievement”. In the educational context, it refers to the phenomenon whereby every school and teacher is under pressure to ‘embellish’ achievement records (of individuals and schools) in order to fulfil students’, parents’, MOET’s, and society’s expectations: these official documents are therefore often very far from reality but marks and results in competitions are still important.

At the socio-cultural level, the enormous challenge to English learning is the lack of an environment for practicing and using English. This is due to the nature of the Vietnamese social context. Na did not have a chance to practise the language she was learning, not until she got the job at a foreign based company. As English is a foreign language in Vietnam, naturally, both learners and teachers have no immediate English-language needs and therefore, lack motivation to learn English. What is arguably worse is the current lack of communities of practice as revealed through the interview data. was almost alone on her language proficiency maintenance and development. Although there were 10 other language teachers in her schools, they were of different age groups and had different interests. There were group meetings every month, yet these were mainly to help completing school paper-work, developing test materials, or discussing teaching and class management difficulties. There were few language proficiency related activities. Training and support are not often available for new or individual teacher. Only low levels of support can be provided in terms of materials, and libraries. These difficulties have also been reported in similar studies conducted by Le and Do (2012) and Nguyen (2011). In addition, while most of the participants have access to the Internet, they all seem to be unaware of Web 2.0 interactive and cooperative features. In context like rural areas with limited facilities and human resources, perhaps introducing and promoting participations in virtual communities of practices would be a meaningful solution before more contextualized and long-lasting communities could be established.

Conclusion

Before drawing the conclusion, it is important to acknowledge that this study is descriptive in nature and did not intend to make any decisive conclusions. Despite such limit, this study has revealed the participants’ less than satisfactory responses to new policy. It is strongly believed that there is no reason to suspect that the study’s results do not reflect the wider situation in Vietnam. Perhaps the most important finding of the study is the teachers’ discontent with their low language proficiency despite their negative reaction to educational change. This tension, on the one hand, discloses the participants’ willingness to learn and improve themselves and longing for support and training programs. On the other hand, it exposes the perception of most participants that the goals of teaching English at school levels were still mainly teaching vocabulary and grammatical structures. Such perceptions required a more in-depth investigation and need to be changed for a better quality of language teaching and learning.

The many factors underlying this tension have been categorized into three overlapping circles namely personal, school-related and sociocultural challenges. Due to the complicated interplay among different factors, a purely quantitative approach to the topic leaves much to desire. This paper suggests that a qualitative perspective would contribute meaningfully to understanding different interconnected factors challenging teachers’ willingness and dedication regarding language proficiency development. The close interdependence of the three circles of challenges demands a holistic solution to the daunting task of maintaining and improving EFL teachers’ language proficiency in this context.

Particular to the context of Vietnam, the study has important implications with regard to NFL2020’s current intensive test-preparation courses to improve teachers’ English proficiency. As an attempt to improve the quality of language teaching and learning, it needs to do more than drilling teachers to pass the B2 standard test could never cure the complex problems regarding teachers’ low language proficiency. A training course whose focus is on MOET’s attempt, therefore, could only function as a bandage solution at best, tending to soothe the surface cut without touching the deep root of the problem. In order to make a meaningful contribution to solving the matrix of challenges teachers are facing in order to improve their language proficiency, it is necessary to employ a more holistic approach with better collaboration among different forces at different levels. There must be macro-changes including reforming the traditional grammar- based testing system, eliminating achievement and formalism diseases, promoting a supportive environment for language use and practice, renewing pre-service teacher training, and conducting more frequent and more practical training and supporting programs for in-service teachers. In addition, it is important to realize that teachers are different individuals with different difficulties. A one-size fit all approach would be less effective. Questionnaire or oral interview can be used to seek such valuable information which would contribute greatly to designing and offering adequate programs suitable for these teachers. As argued by Wedell (2009), education reforms need to begin with the beginning. The teachers, the main protagonists, should not be left ignored during the process. Rather, their voices need to be heard so that their needs can be catered for in long-term and meaningful supporting programs.

Acknowledgements

The author(s) declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

Braine, G. (2010). Nonnative speaker English teachers: research, pedagogy, and professional growth. New York: Routledge.

Butler, Y. G. (2004). What level of English Proficiency do elementary school teachers need to attain to teach EFL? Case studies from Korea, Taiwan, and Japan. TESOL Quartely, 38(2), 245-278.

Cooper, T. C. (2004). How foreign language teachers in Georgia evaluate their professional preparation: A call for action. Foreign Language Annals, 37(1), 37-48.

Crystal, D. (1998). English as a global language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Davies, A. (1991). The native speaker in applied linguistics. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Farrell, T. S. C. (2007). Reflective language teaching: From research to practice. New York: Continuum.

Fraga-Canadas, C. P. (2010). Beyond the classroom: maintaining and improving teachers' language proficiency. Foreign Language Annals, 43(3), 395-421.

Grassick, L. (2006). Primary Innovations: Summary Report. Vietnam: British Council.

Hayes, D. (2008). Primary English Language Teaching in Vietnam: A research study. Report for British Council/ Ministry of Education. Vietnam: British Council.

Le, C. V. (1999). Language and Vietnamese pedagogical contexts Paper presented at the The Fourth International Conference on Language and Development, Hanoi, Vietnam. Retrieved from http://www.languages.ait.ac.th/hanoi_proceedings/canh.htm

Le, C. V. (2007). A historical review of English language education in Vietnam. In Y. H. Choi & B. Spolsky (Eds.), English education in Asia: History and policies (pp. 167-180). Seoul: Asia TEFF.

Le, C. V., & Do, C. T. M. (2012). Teacher preparation for primary school English education: A case of Vietnam. In B. Spolsky & Y.-i. Moon (Eds.), Primary school English-language education in Asia: From policy to practice (pp. 106-128). New York: Routledge.

Medgyes, P. (1994). The non-native teacher. London: Macmillan.

Medgyes, P. (1999). Language training in teacher education. In G. Braine (Ed.), Non-native educators in English language teaching (pp. 177-195). Mahwah, New Jersey, London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Medgyes, P. (2001). When the teacher is a non-native speaker. In M. Celce-Murcia (Ed.), Teaching English as a second or foreign language (pp. 415-427). Boston: Heinle and Heinle.

Moon, J. (2009). The teacher factor in early foreign language learning programmes: The case of Vietnam. In N. Marianne (Ed.), The age factor in early foreign language learning (pp. 311-336). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Nguyen, H. N., & Dudzik, D. L. (2013). Vietnam's English Teacher Competencies Framework: Policies, Context, Basis and Design. Paper presented at the Teacher Competency Frameworks: Developing Excellence in Teaching, Kuala Lumpur.

Nguyen, H. T. M. (2011). Primary English language education policy in Vietnam: insights from implementation. Current Issues in Language Planning, 12(2), 225-249.

Nunan, D. (2003). The impact of English as a global language on educational policies and practices in Asian Pacific region. TESOL Quartely, 37(4), 589-613.

Pasternak, M., & Bailey, K. M. (2004). Preparing nonnative and native English-speaking teachers: Issues of professionalism and proficiency. In L. D. Kamhi-Stein (Ed.), Learning and teaching from experience: Perspectives on nonnative English speaking professionals (pp. 155-175). Michigan: The University of Michigan Press.

Schulz, R. A. (2000). Foreign language teacher development: MLJ perspectives 1916-1999. Modern Language Journal, 84(4), 495-522.

Tang, T. (2007). Investigating NNS English teachers' self-assessed language proficiency in an EFL context. Unpublished MA Thesis, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec.

Vietnamese Government. (2008). The government: No.1400/QĐ-TTg Decision on the approval of the project entitled "Teaching and Learning Foreign Languages in the National Education System, Period 2008-2020".

Wedell, M. (2009). Planning for educational change: Putting people and their contexts first. New York, NY: Continuum.

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning and identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.