Abstract

The process of preparing candidates for year-end high-stakes examination is a daunting task for teachers. This paper reports on three teachers’ experience of teaching students to sit for the standardised national English exam and IGCSE English, both from two different curricula. The findings from the qualitative case study revealed that the initial workshops that they had attended did not adequately prepare them to teach the new course. However, after a prolonged period of teaching high-stake exam classes, they overcame the confusion and could differentiate the nuanced differences in the syllabus requirements, test formats and contents. The teachers’ initial experiences showed that they relied on the “takeaway” materials provided during the workshops but became more independent in sourcing for materials that could be used for either or both the courses simultaneously. They also transferred their existing knowledge from one course to the other and focused on what was important to answer exam questions. Their teaching approach and practices were aligned to the high-stakes exams. The findings underline the complexities of teachers’ lived experience in high-stakes exam environment, and how they juggle with both curricula needs. Therefore, guidelines and continuous support should be offered to ensure sustainability of quality teaching experience.

Keywords: Business ethics, business operations, pharmaceutical industry

Introduction

High-stake examination results are not only taken as the pinnacle of learners’ academic achievement but also as their schools’ accountability towards teaching and learning process. In the epicentre of school accountability is teachers’ shared responsibility (Ariffin et al., 2018; Dworkin & Tobe, 2014) towards their students’ success. Teachers are keenly aware that high-stake examination results have a direct bearing on the students’ future, and how they are trained to perform during the few days of the examinations may determine the failure or success of entering post-secondary, pre-university or entry into the job market.

In line with the increasing importance placed on global competitiveness, it is not surprising that some stakeholders, e.g. parents and administrators, have insisted that students are equipped with not only local standardised examination certificates but also with international ones. They perceive that students who are equipped with more than one certificate would have an added advantage against their peers who have only one. Consequently, this has increased the demand for international comparative exams (Lingard et al., 2014). The onus then lies mainly with the teachers teaching the exam classes to ensure that their students are prepared for both. While it is generally understood that teachers who need to prepare their students to sit for high-stake exams are under tremendous pressure due to societal expectations and the need to complete the syllabus, there is a blatant lack of studies that have reported on teachers’ lived-experience in a dual high-stake examination environment. In the Malaysian education system which adopts a standardised exam at all the public secondary and pre-university levels, very few studies have focused on teachers’ lived experiences despite teacher agency (Priestley et al., 2015) being acknowledged as a key factor for student success. One cannot deny that a successful lesson is often attributed to the teacher cognizing about the syllabus and acting on it within the constraints of space, time, students and other formalities.

Teachers who are given the responsibility of teaching high-stake exam classes need to keep tab of directives or changes in policies as not doing so may put their students at risk of performing poorly or failing. Inadvertently, the top-down decisions impose some restrictions on teachers’ way of thinking and acting on their teacher roles. Au (2011) asserts when top-down decisions are made, teachers lose their autonomy; subsequently this leads to narrowing of the curriculum and increase in didactic methods of teaching. This too had been Shohamy’s (1994) concern decades earlier when the researcher discussed how emphasis on tests created “strained feelings” among teachers. They turned to “teaching to the test”, referred to past tests to teach content and conducted drills with worksheets that looked like tests. Although they engage in teaching activities, past research revealed that class time is used to guide students ace the high-stake exam rather than to expand knowledge of the topics. If this is prevalent across high-stakes exam environment, it is then necessary to further unravel the lived-experience of those teachers who perform their duties under the duress of accountability towards students’ performance.

While related literature does inform to a certain extent the adverse effects of high-stake exam (e.g. see Au, 2011 for a comprehensive survey) on classroom teaching and learning, most studies provide quantitative data (e.g. Zakaria et al., 2013). This leaves a gap in knowledge on teachers’ lived-experience as compared to students’ learning outcomes or achievements (e.g. Goh et al., 2017; Lee & Reeves, 2012), and teacher anxiety (e.g. Gregory & Samantha, 2006; Suhirman et al., 2016) in high-stake environment. Worse, there is a dearth of studies of teachers’ experience specifically on how they deal with “routine tasks” of teaching and other tasks in dual examination system environment. The current study addresses the dual examination system environment as there is a need to understand what teachers did with instructions stemming from two different sources as part of their daily work.

Purpose of the Study

This study aimed to shed some light on the phenomenon that is often overlooked in the quest for exam results; teachers’ lived-experience in dealing with high pressure dual examination system environment.

Research Questions

The research question posed is: What are teachers’ lived experience of teaching in a dual high-stake examination environment?

Research Methodology

Instruments

The main data for this qualitative case study was obtained from semi-structured interviews with three teachers who were assigned to teach English for students who would be sitting for the IGCSE English as Second Language (henceforth IGCSE English) and SPM (SPM refers to the Malay acronym for Sijil Pelajaran Malaysia or the Malaysian Certificate of Education awarded at the end of high school. It is equivalent to the Cambridge O level.) English 1119 (henceforth SPM English) high-stakes examinations.

Participants

Teacher 1, Teacher 2 and Teacher 3 were senior teachers at the school and were trained formally in teaching English. As all teachers are screened and trained according to government regulations prior to postings at schools, it could be generalised that all government-employed teachers in service have knowledge of pedagogy and classroom teaching due to their training. What would set them apart is the localised experience that the school environment afforded them, which is the reason why the study purposively selected and focused on the three trained teachers who taught English in the school that had introduced a dual exam system due to new top-down policies.

At the point of investigation, the school (also the boundary of the case study), where the teachers taught had been instructed by the ministry to prepare their students for both high-stakes exams instead of the usual English paper for SPM. The new policy affected Four (15-year olds) and Four Five (16-years olds) classes as the teachers had to prepare them to sit for the IGCSE when they were in Form Four and, the SPM English a year later. However, the teaching and classroom instructions for both would have begun when they were in Form Four. This means that the teachers had to teach the Form Four students IGCSE English and Form Four English syllabus, and when the students moved on to Form Five, the SPM English.

Findings and Discussion

Awareness of SPM English and IGCSE English Subjects

The teachers interviewed revealed that they were aware that IGCSE and SPM English syllabi, examination formats and teaching contents were different. A comparison between the two examination formats and requirements had been analysed by Supramaniam and Nazer (2016) who indicated that both examined writing, reading, listening and speaking skills differently, and have varying formats and contents. This means teachers need to address two different specifications. Indeed, this could be a daunting task, as revealed in the following excerpts. The teachers were asked to describe them verbally. Teacher 1 shared:

Well, it’s rather complex to describe both, but I will try. The IGCSE English as 2nd language has Reading and Writing, and this paper has two types, core and extended papers. Extended papers is based on the core papers, but with more HOTS questions and the essay length is longer, between 150 – 200 words, compared to core – essay is between 100 – 150 words. IGCSE has Speaking test and Listening test, speaking test is based on one-time assessment compared to SPM, which I think you know the format. Two to four-time assessments which give more chances for students to improve. Listening is something like MUET listening test.

Teacher 1’s comments above showed her familiarity with both high-stake examination formats as she managed to describe both syllabi clearly. Furthermore, she was one of the pioneer teachers who was assigned to teach both IGSCE and SPM English and has been exposed to the contents in earlier workshops. On the other hand, Teacher 2 mentioned that he too was familiar with both syllabi but, did not verbalise the details when queried further during the interview. His response was a general one:

…that somehow there is a similar essay of IGCSE English as first language which is Continuous Writing, but with different marking scheme and total of marks.

He admitted that he was still ‘confused’ dealing with the SPM English and IGCSE English syllabi requirements. Although he was assigned to teach IGCSE English as a second language, he was sent to attend the IGCSE English as the first language course instead. When further probed on why he was sent for this course, he responded:

…when the dual system started, it wasn’t clear enough, what should be taught, but I learnt that students need to sit for Checkpoint in Form 2 which is in the first language, and I think that is why the two of us were sent to attend the IGCSE English as first language course and the rest for IGCSE English as a second language.

However, the initial confusion eventually dispersed after he continued teaching IGCSE English as a Second Language and SPM English. At the point of research, he had entered the second year of teaching in the dual system. He further commented:

After sometime, I am now quite familiar with the formats and the marking schemes for IGCSE English and for SPM English as I have taught SPM for many years and even had the experience of marking SPM English papers for a couple of years. There are some changes in the Continuous writing, for example, in the past years, there is no One Word Essay topic.

Besides Teacher 1 and Teacher 2, Teacher 3 was queried about her awareness of the dual high-stake examination formats. She shared the following:

The IGCSE English as a second language essay, even requires them to write not more than 200 words, the language should be precise and testing their critical thinking, besides they need to include some relevant idiomatic expressions and proverbs, if not they can’t get the highest band, band 6, even with clean and clear language.

It could be inferred from all the three teachers’ comments that they had gained some awareness of the differences between IGCSE and SPM English examination formats and syllabi contents from the workshops and courses they were asked to attend by the school administration. Although the initial phase was the most challenging since none of the teachers had any prior experience of teaching IGCSE English, they managed to figure how to manage both courses. As Teacher 1 disclosed, it was “a new exciting experience”. Although the workshops organised by the ministry provided information on the new course, there was no follow up or opportunity for further collegial interactions among the teachers. The one-off workshops are often designed for teachers to take-away information, ideas or technical know-hows (e.g. interactive whiteboard- Perinpasingam et al., 2019), and therefore these expand the teachers’ existing repertoire of knowledge, instead of actual practice that they need to deal with when they return to schools. The addition of new skills to existing repertoire is most unlikely to transform teachers’ practices as compared to teacher professional development ones (Ko et al., 2006; Stein et al., 1999). This means that teachers who are assigned to teach the new course in a more holistic way may continue their exam-oriented practices and neglect other non-academic activities like music, swimming and robotics that parents demand from education providers (Shen et al., 2018).

Teaching Resources for SPM English and IGCSE English Subjects

As the IGCSE was a new course, it was necessary to query the types of teaching materials that the teachers used within the dual high-stake examination systems and where they sourced these materials. Teacher 1 shared that although it was a common practice among English teachers to use the textbooks prescribed by the Ministry of Education (MoE) as the main source of teaching materials, surprisingly she and her colleagues did not do so:

We don’t actually use textbooks either for IGCSE or Form Five MoE Textbook, but only use the Literature Textbook for lessons on Poems and Form Five Novel.

She explained the reason why as thus:

It is rather lengthy to explain but in (our school) we are discouraged to use the MoE textbook except for literature components. May be to expose the students with the current issues and may be to challenge the teachers to prepare more holistic lessons plans with the current issues for the students to know, as well to be more creative and more knowledgeable by reading more I assume.

Hence the researcher queried where she obtained her teaching materials, to which she stated the following:

I also depend on the internet for my lessons plan and teaching resources as well as IGCSE books at the library and Photostatted the exercises. I also use the books which my colleagues bought, for example IGCSE books on writing summary and vocabulary.

Comparatively, Teacher 2 relied more on the materials obtained from the courses run by the ministry. He said:

..it was hard at first, as there were not much teaching materials to use, except the materials the teachers got from the courses they attended… It is easier to download past years SPM English questions papers and the marking schemes, but not for IGCSE, it is not available unless the school subscribed it online which is rather costly. So, I make full use of the ones we got from the courses.

However, after teaching for more than a year, Teacher 2 seemed more confident and resourceful. He shared:

Now it seems clearer what I should teach as we have a book for teachers, not only it provides the materials but comes with the comprehensive lesson plans, thought we have to adapt and adjust some activities, … Before this, as we didn’t have specific books to use to teach IGCSE ESL, I would borrow books from the library, browse the relevant topics and exercises and get them Photostatted. Usually, the Coordinators for each level would prepare teaching materials and exercises, but the class teachers respectively prepared their own lesson plans based on the materials provided.

Besides Teacher 1 and Teacher 2, Teacher 3 also commented on the teaching resources that she used for her IGCSE lessons for Form 4:

I use most of the materials that I got from the courses and workshops I attended. But still, I used whatever materials that I can get either from the library, internet or my colleagues who are teaching the same levels.

However, she added that recently they received their textbooks for the newly introduced IGSCE course:

For this year, we just got the student’s text book for IGCSE English as a second language, but we have decided that students will use the books only when we require them to use. The books are rather costly to be given to the students as we know the risk for them to lose or spoil the books. We have one good book for teachers, which is the IGCSE ESL Teacher’s Pack, which comes with suggested activities and lessons to be used together with the Students Workbook. However, we Photostatted the articles and exercises for the students, as the students’ workbooks are limited.

The teachers’ responses above showed that they used various resources to teach the dual high-stake examination courses such as textbooks provided by the MoE, materials obtained from the Internet, the library, the teacher pack given during the workshops, materials provided by the course coordinator, and materials bought or borrowed from other colleagues. Although there were some problems during the initial stages, the teachers were resourceful and used whatever resources that were available. However, Teacher 3’s response reflected that she was dependent on the IGCSE ESL Teacher’s Pack obtained from during the workshop. Moreover, the original books were expensive or limited, which forced them to make copies for their students. Overall, the three teachers’ responses showed that the main point of reference for the new course was the materials given to the teachers during the workshop by the ministry officials. This is not surprising that in the top-down policy change, teachers should be given training and the materials to help them carry out their lessons when they return to their respective schools. However, the efficacy of a one-time workshop instead of continuous support (e.g. professional development) is questionable (Ko et al., 2006; Perinpasingam et al., 2019). The following sections investigates further how these teachers used the “take-away” materials and utilised them for their classes.

Planning Content of Lessons for SPM English and IGCSE English

The teachers who were involved in teaching English in the dual high-stake IGSCE and SPM examinations contexts were interviewed to understand their experience when preparing to teach their students who had to sit for both examinations. For IGCSE, Teacher 1 shared the following:

For IGCSE English, I always try to use authentic materials, if possible, on foreign settings, something global. Though… sometimes the students may not even know what actually happens in our country. I will share some issues which happened in our country, for example, the issue on bauxite mining in Kuantan and any other current issues that I could remember and relate to.

Teacher 1’s comments showed that she used authentic materials from local (e.g. at the point of data collection, bauxite mining was an issue widely discussed in the media) and foreign contexts. She kept herself abreast with current news in order to discuss them with her students in the classroom. On the same note, Teacher 2 shared what he did for IGSCE:

As for IGCSE English, I would take them to the computer lab and assign them in a small group to browse and collect information about the global issues, such as World Diseases, Humans’ Trafficking, Lack of Food Supply and others, for them to present in the next class. They will not only learn about the issues, but many more... especially it helps them to learn new vocabularies and to expose their minds on the issues.

Like Teacher 1, he too exposed the students to current news, e.g. ‘World Diseases’, ‘Humans’ Trafficking’, ‘Lack of Food Supply’ which brought outside issues to the classroom.

Moreover, Teacher 2 added that he prepared different or extra handouts for advanced learners, as he had a heterogenous class with different levels of English competency and it was difficult to teach “a balanced skill of all areas of language learning”.

Similar to the other teachers, Teacher 3 too seemed to have a similar approach in preparing and teaching her Form 4 IGSCE class:

They need to know about some global issues, so I will ask them to present different themes or topics related present global issues, something common, like pollution or environmental effects, drugs abuse and trafficking, world diseases. This is because IGCSE questions, especially reading comprehension will normally use authentic articles on current issues that is why they need to know some common world issues... I also did some lessons with my students on idioms and proverbs, as for IGCSE English they need to include few idioms and, or proverbs to score better marks. The lessons are also good for English SPM, especially, for continuous essay.

However, Teacher 3’s comments also revealed that the motive to compel her students to learn about global issues like pollution, environmental effects, drugs abuse and trafficking and world diseases is because of the themes addressed in the IGCSE reading comprehension passage questions. When the other two teachers’ comments were re-examined, the main motives seemed to be to encourage the students ‘to learn about the issues’, ‘to learn new vocabularies and to expose their minds’ on current general issues. Teacher 1 referred to the bauxite mining issue in Malaysia. While these attempts could be interpreted as being culturally responsive (Richards et al., 2007) as authentic external issues were brought into the classroom, the teachers continued to relate to exams and the possibilities of those topics being questioned in the high-stake exams. Another example is Teacher 2’s disclosure that it was more challenging to address different levels of competencies in such a context although he tried to have additional materials for the more advanced ones. This is an example of teaching and learning aspects that is constricted in an exam-oriented environment (Au, 2011). In such environment, teachers’ creativity and strengths to make the lessons meaningful are restricted too (Frawley, 2014). To further unravel the influence, teachers were questioned further on both the exams and components.

Conforming Teaching Approach and Content to Exam Components

In the earlier section, queries on the teaching content revealed that the participants’ choice of topics were not only the need to expose students to the issues but also because they would most likely be questioned in the exams. For instance, idioms and proverbs were taught because students “need to include few idioms and, or proverbs to score better marks’ in IGCSE English, and “the lessons are also good for English SPM, especially, for continuous essay” (Teacher 3). The following findings further validate that teaching content and other classroom practices were often related to the high-stakes exams. For SPM English, Teacher 1 shared,

I have to choose some lessons, especially when they don’t have much time to practise various essays for Directed Writing and Continuous Writing. But basically, for SPM Directed Writing, I need to expose and remind them on the Formats, such as for formal letter, the recipient address, Salutation, tone of language should be use accordingly, and for Continuous Writing, normally I focus more for my students to practise more on writing narrative essay, rather than other types of essay, such as argumentative which is rather hard for most of them.

When comparing with the IGCSE English paper, she further explained:

Well, for IGCSE ESL, students don’t have to use much expressive words and less figurative words compared to SPM English for narrative writing.

Clearly for Teacher 1, the choice of essays to be taught to the students, i.e. “” and “” is because it is generally presumed that narrative essays were easier than argumentative essays to score better marks in writing. Similar exam-driven practices were also evident in Teacher 3’s comments who taught Form Five students who would be sitting for the year-end standardised national exam.

We have compilation books of SPM Past Years Questions for the students to practice, but usually, for Essay, I would emphasise more to teach my students good narrative essay, as this essay is easier compared to other types of essay, such as argumentative or descriptive. I would provide them with some examples of interesting essays, teach them to write various structures of sentences in every paragraph, to make it interesting… Students have to be careful as when to choose what kind or narration, as in SPM, the narration can be as “end the essay with a specific phrase or sentence” which requires students to prepare their plots better, they have to be smart enough to plan and write.

Like Teacher 1, Teacher 3 too chose to emphasise narrative essay as it was “easier compared to other types of essay, such as argumentative or descriptive”, meaning that students would be able to score better in this form of essay compared to the other two types. This is not surprising as instructors have different understanding of this genre and therefore do not adequately teach it to students (Wingate, 2012). As such, students may learn partial or incorrect concepts of argument which may result in poorly written essays. Clearly, the concern is not guiding students to develop their critical voice or developing a position in an academic debate, or to improve their skills in all essay types, but rather to select the ones that could be easily learned and excelled in to gain the most marks.

Teacher 2’s responses seem to validate the “teach for more marks” attitude:

I would always use some past years questions, so that my students would have much ideas of what the actually questions are, they don’t have much problem to write directed writing, as points are given. And even for students with problems to expand the points, I always ask them to expand the points given by asking questions based on the points, but, they may face some problems to write the narrative essays, especially either the inconsistency of tense, especially when narrating, I always tell them to write in Past Tense, as they were narrating…Students have to be taught to plan for the narrative essay, so that the story would be interesting to the examiners, for them to get better marks. For Continuous writing, dull story will not score good marks even with no or less mistakes in grammar. Therefore, I also ask them to memorise some good narrating sentences or phrases, but not the whole essay, they can use the story they have read but with some changes on the plots.

In could be summed from the teachers’ responses above that their teaching approaches and strategies were driven by the needs of the dual high-stake examinations instead of knowledge expansion. Placing much importance on essay writing seem quite natural as the continuous essays for SPM carries 50% of the total writing marks. Such high value placed on the essay genre seemed to reverberate to the classroom where teachers were compelled to emphasise on the easiest way for good results, how to ‘score good marks’, how to make it ‘interesting to the examiners’ and memorising ‘some good narrating sentences or phrases’.

Alternatively, more could be focused on the different genres of essays and how learners could communicate their ideas to others within the scaffolds of the communicative syllabi. However, as much as the teachers would like to teach for knowledge, as Teacher 1 had in discussing issues that affected the nation (e.g. bauxite mining), they had to ensure that the students were prepared for the different papers for both exams. Table 1 below shows a summary of the contents of SPM English Language (English 1119) and IGCSE English as a Second Language examination (Supramaniam & Nazer, 2016).

The summary of content in Table 1.0 above shows that one of the differences in the syllabuses is the literature component which is not assessed in the IGCSE English paper but is a component in the SPM papers. This means the English teachers need to teach literature for SPM which include novels and poems that would be covered in Form Four and Form Five classes. Teacher 1 shared her experience of preparing her students for the literature component:

… well, sometimes I have to integrate the syllabus, as MoE does include literature components, especially Poems for Form 4 syllabus, which will come out in SPM Exam in Form 5… I don’t think we have much time to teach the Form 4 Poems when they are in Form 5, as there are few more Form 5 poems to teach… I need to do some lessons on Directed Writing, such as writing reports, letters of complaint, informal letter, speech and summary. SPM English summary is rather complex than IGCSE.

Clearly the teacher juggles between what had to be covered for the literature component and the communicative component of the upper secondary classes in preparation for the high-stakes exam. Much of the communicative components that are taught for the SPM English would also allow the students to answer the IGCSE papers. The emphasis on the SPM paper is again seen in the teaching of the oral skills as marks for oral assessment are counted in the overall SPM results but not for IGCSE.

Teacher 2 explained his experience as thus:

I have to consider to do SPM English Oral Tests, make them read the Form 5 Novel, and expose them to SPM Format of Paper 1 and Paper 2….as the for ULBS for students in Form 4, I might conduct at least one ULBS, to cater for MoE’s ULBS…SPM essays are not only about correct and grammatical sentences, they need to write at least 350 words essay interestingly and creatively, and apply HOTS (Higher Order Thinking Skills). But mostly, I don’t really have time to ask my students to practise other types of essays except narrative essays.

Teacher 3 response is similarly focused on selective teaching.

Yet, I still need to cover some lessons based on MoE, especially the poems, so that they are not burdened with more lessons on the poems as when they are in Form 5 … Even for IGCSE syllabus, when the students are in Form 4, I have to be very selective what to teach and what is less important to exclude. But I will sometime use Past questions papers just to make them aware of the formats and what they should do. This will at least give them more ideas of the sections that they need to improve and focus.

Clearly all the teachers showed their concerns in completing the ministry’s SPM English syllabus especially the poems. Teacher 2 explained that despite the well-prepared Scheme of Work, he finally used drilling method and practised the past years and “cloned questions” papers. It was also evident that they were more concerned in completing the SPM syllabus which had varied items tested.). Unless they students were exposed to the literature components, they would not be able to answer the question paper. For IGSCE, the literature components were not integrated with the English paper and students were not dependent on the literary texts. Hence this explained the teachers’ greater concern for dealing with the more challenging SPM examination.

The participants’ responses seem to echo Au (2011) comprehensive review that teachers often drilled their students with multiple past years exam papers and tips to equip them with the necessary skills to obtain better scores. They neglect communicative approaches (Cimbricz, 2002) and other topics which are not tested (Au, 2011) which leads to narrowing of the curriculum (Berliner, 2011). In the current environment that involves the national education and IGCSE, it is highly appropriate to frame is as a case of “narrowing of the curricula”.

Conclusion

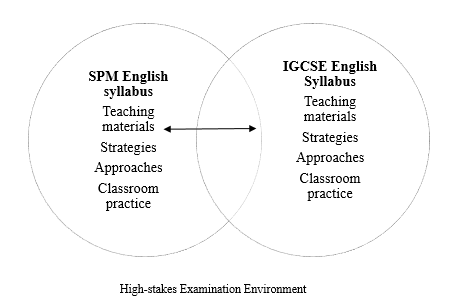

The findings reported in this paper shed some light on the complexities involved in teaching a dual high-stakes exam environment, specifically the IGCSE English and SPM English courses. Although the limitations to the study was the small number of teachers at one site, unravelling their experience was important to understand the journey of meeting curricula needs and preparing students for stellar results. Reiterating the gap in literature on teachers’ experience of dealing with teaching the two courses, the findings showed that they were experts in teaching the national English syllabus but when the new course was introduced, they had to negotiate their existing practices and knowledge with the demands of the second course. All three experienced some confusion at the early stage when the new course was introduced but after a prolonged period of teaching, they transferred some of the existing repertoire to teaching the new course. The emerging themes from the study reflected that they dealt with teaching resources, course content and pedagogical practices within the overlapping boundaries of the two courses, which is represented in Figure 1 below:

The two circles in Figure 1 represent the high-stake exam environment in which the teaching and learning occur although the course syllabi clearly provide instruction for teaching. Each course has its own prescribed content. However, in a dual system, the teachers found a common ground with both courses and taught what was applicable for both, e.g. essay topics, idioms and proverbs. This strategy seems rational as there are many components of the target language that are general and could be easily transferred. Hence the transfer of pedagogical knowledge is represented by the arrow in the overlapping area in Figure 1. However, the syllabi of both courses demand that specific skills are taught, for instance summary writing itself could be either a general one or focused; as such problems may arise when the nuanced differences are not addressed in class.

The onus is on teachers teaching the exam classes to carry out the top-down policy requirements in a way that would prepare them for life-long learning. As the study has shown, facing constraints and pressure seems to contribute to their lived experience but after a prolonged period of time, teachers negotiate their existing practices to adapt to the new courses or change in policies; however, the negotiation of knowledge and practice should focus towards equipping their students with communication skills that go beyond exam contexts. In a way, they could discover what other value-added skills and experience they could offer their learners within the boundaries of the high-stake exams.

On the other hand, policy makers must consider the implications of standardised tests and exams, and while these may not be avoided completely, they could explore alternatives to align policies and top-down instructions through continuous teacher development programmes and intermittent needs analysis. The latter could inform policymakers of teachers’ readiness and other issues like teacher-wellbeing and quality of life at the workplace. During the initial stages, it is important to provide continuous support rather than one off workshops. Besides providing information, workshops could incorporate hands on training sessions for experiential learning which could alleviate much anxiety. Such workshops also provide opportunities to create networks and support systems that could be extended at school or district levels. Often, the benefits that would emerge from such collaborations may spill over to shared value, quality of teaching and material development. While high-stakes exams may not be totally discarded due to their coveted value in society and practicality, the process of learning and providence of quality teaching must not be overlooked.

References

Ariffin, T. F. T., Bush, T., & Nordin, H. (2018). Framing the roles and responsibilities of excellent teachers: Evidence from Malaysia. Teaching and Teacher Education, 73, 14-23.

Au, W. (2011). Teaching under the new Taylorism: High‐stakes testing and the standardization of the 21st century curriculum. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 43(1), 25-45.

Berliner, D. (2011). Rational responses to high stakes testing: The case of curriculum narrowing and the harm that follows. Cambridge Journal of Education, 41(3), 287-302.

Cimbricz, S. (2002). State-mandated testing and teachers' beliefs and practice. Education policy analysis archives, 10(2), 1-21.

Dworkin, A. G., & Tobe, P. F. (2014). The effects of standards based school accountability on teacher burnout and trust relationships: A longitudinal analysis. In D. Van Maele, P. B. Forsyth, & M. Van Houtte (Eds.), Trust and school life: The role of trust for learning, teaching, leading, and bridging (pp. 121–143). Springer Science + Business Media.

Education Performance and Delivery Unit. (2011). Ministry of Education Malaysia. https://www.padu.edu.my/about-the-blueprint/

Frawley, E. (2014). No time for the 'Airy fairy': Teacher perspectives on creative writing in high stakes environments. English in Australia, 49(1), 17-26. https://search.informit.com.au/documentSummary;dn=381501270146252; res=IELAPA

Goh, P. S. C., Yusuf, Q., & Wong, K. T. (2017). Lived Experience: Perceptions of Competency of Novice Teachers. International Journal of Instruction, 10(1), 21-36. http://www.e-iji.net/dosyalar/iji_2017_1_2.pdf

Gregory, J. C., & Samantha, S. B. (2006). Addressing test anxiety in a high-stakes environment. Corwin.

Ko, B., Wallhead, T., & Ward, P. (2006). Professional development workshops: What do teachers learn and use. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 25(4), 397-412.

Lee, J., & Reeves, T. (2012). Revisiting the impact of NCLB high-stakes school accountability, capacity, and resources: State NAEP 1990–2009 reading and math achievement gaps and trends. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 34(2), 209-231.

Lingard, B., Sellar, S., & Savage, G. C. (2014). Re-articulating social justice as equity in schooling policy: The effects of testing and data infrastructures. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 35(5), 710-730.

Malaysia Education Blueprint 2013-2025. (2013). http://www.moe.gov.my/index.php/ en/dasar/pelan-pembangunan-pendidikan-malaysia2013-2025

Perinpasingam, T., Chin, H. L., & Supramaniam, K. (2019). Needs Analysis of Teacher's use of the Interactive White Board. In P. Alagappar, M. T. W. Yee, & S. N. Mohd Nur (Eds.), Approaches Through Blended Learning for Teaching and Learning (pp. 133-142). UPM Press.

Priestley, M., Biesta, G., & Robinson, S. (2015). Teacher agency: An ecological approach. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Richards, H. V., Brown, A. F., & Forde, T. B. (2007). Addressing diversity in schools: Culturally responsive pedagogy. Teaching Exceptional Children, 39(3), 64-68.

Shen, H. J., Basri, R., & Asimiran, S. (2018). Relationship between Job Stress and Job Satisfaction among Teachers in Private and International School in Malaysia. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 8(12), 275-286.

Shohamy, E. (1994). The use of language tests for power and control. In J. Alatis (Ed.), Educational linguistics, crosscultural communication, and global interdependence (pp. 57–72). Georgetown University Press.

Stein, M. K., Smith, M. S., & Silver, E. (1999). The development of professional developers: Learning to assist teachers in new settings in new ways. Harvard Educational Review, 69(3), 237-270.

Suhirman, L., Admowardoyo, H., & Husain, J. (2016). Perception of EFL Teachers’ Satisfaction on Pedagogical Process. International Journal of English Linguistics, 6(5), 170-179.

Supramaniam, K., & Nazer, A. (2016). Two rabbits in a hat: Comparison of SPM English language and IGCSE English as second language high-stakes test. Proceedings of the National Conference of Research on Language Education (pp. 218-226). Melaka, Malaysia.

Zakaria, N. A., Samad, A. A., & Omar, Z. (2013). Pressure to improve scores in standardized English examinations and their effects on classroom practices. International Journal of English Language Education, 2(1), 45-56.

Wingate, U. (2012). ‘Argument!’ helping students understand what essay writing is about. Journal of English for academic purposes, 11(2), 145-154.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.