Examination Reform at the Sibelius Academy From 1974-1980: Implementation and Communication of Organizational Change

Abstract

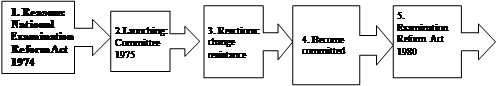

This is a qualitative case study and the historical overview of the first part of examination reform process at the Sibelius Academy from 1974-1980. The purpose of the study is to discover how the act and the decision made to reform the examinations were implemented at the Sibelius Academy. The research problem was to determine the process that the examination reform followed. How was the examination reform implemented at the Sibelius Academy? How was the reform communicated? What were the reactions of the people involved when they heard of the reform? Data was gathered through interviews with 11 participants. The research method was qualitative content analyses of the interview material combined with the reflections of the writers who were former Sibelius Academy students. In the Findings, five phases of the reform process are introduced through qualitative interview material. These phases are reasons, launching, reactions, becoming committed and examination reform. This reform was going to lead the way developing the Sibelius Academy towards a status of a university in the future.

Keywords: Organizational change, academic institution, examination reform, higher music education

Introduction

In the 1970s, examination reform spread across schools and universities in Europe. Even higher education in Finland would be irreversibly affected by this thorough reform. For arts academies in Finland, it was going to be an even more meaningful reform than for the other universities in the field of traditional sciences. The examination reform itself would last for years. The official decisions at the university level would be made due to the Examination Reform Act enacted by the Government of Finland on 19 December 1974. This paper will discuss the process of examination reform at the Sibelius Academy, an academic institution of higher music education in Finland. It will concentrate on the period before the reform. The first steps in implementing the reform were crucial for the future. The status of the Sibelius Academy would change and provide new opportunities in the field of music instruction. The process would involve new structures and new ways for administrators and academics to think and act.

The Sibelius Academy, founded in 1882 by a private initiative, is today the largest music academy with university status in the Nordic countries. Since the beginning of 2013, it is a part of the University of the Arts Helsinki. The examination reform in the 1970s was one of the most important events in the history of the Sibelius Academy. The outlook for organizing higher education had changed. The mission for higher education was also shifting. The economic resources compared with the increasing number of students, academic unemployment and the demands of the society created distrust towards traditional free academic studies.

Sibelius Academy as an academic institution is built on artistic values but at the same time depended on financial aspects as well. According to Daigle and Rouleau (2010), arts organizations are built on multiple tensions between artistic and managerial values. Arts organizations consist of individuals and groups with different interests and ways of perceiving and evaluating the artistic processes. Agreements between arts and management can be achieved despite their contradictory natures (Chiapello, 1998). Because educational and financial policies affecting music education come from both governmental and other entities whether or not music education is connected with them, some of their effects are apparent and easily measurable while some others are not. Jones (2009) writes about concepts of “hard” and “soft” policies to illustrate the situation of administrative practices concerning the music educational field.

The knowledge of how to handle these agreements and processes is minor and according to Maitlis and Lawrence (2003) there is very little scientific research and understanding of the processes required to sustain them over time. The aim of this study is to increase this knowledge and find answers to questions about the processes that ensure the survival of the organization during the reform.

Problem Statement and purpose of the study

The purpose of the study is to discover how the decision made to reform the examinations was implemented at the Sibelius Academy. Interviewees provided information on the status before the Act came into effect and the effects of the structural and cultural changes that followed.

Research Questions

The research problem was to determine what the process of examination reform was at the Sibelius Academy from 1974 to 1980. How was the examination reform implemented at the Sibelius Academy? How was the reform communicated? What were the reactions of the people involved when they heard of the reform at the Sibelius Academy?

Research Methods

This is a qualitative case study. The data collection of the research consists of eleven expert interviews. Nine of them were made personally with the interviewees, one by telephone and one by email. A method of semi-structured interviews has been used. The interviews have been structured and content analysed. According to Saunders, a case study is a development of one or a small number of cases in relation to each other (Saunders et al., 2000, p. 76). The strength with case studies is that different kinds of material and documents can be used, not only interviews. In addition, even direct observation and participation by the researcher are possible (Yin 1994, pp. 33-34). Thus, the researcher, as a former student of the Sibelius Academy, was able to construct an overall picture of the meaning and characteristics of the processes and events within the study.

Findings

The results show that there were different phases during the examination reform process at the Sibelius Academy. In the following, these phases are introduced through the qualitative data of experiences and knowledge of the participants (committee members, teachers, administrators, administrative assistants and students) of the Sibelius Academy from 1974 to 1980.

Reasons

The first phase of the study of the reform consists of the questions on why an examination reform was needed and the reasons for the reform. The examination reform had had its official beginning due to the Examination Reform Act enacted by the Government of Finland on 19 December 1974. Most of people at the Sibelius Academy were aware of it and had even been informed about it. However, our research question is, what did they know about the reasons for the reform? Students and administrators affected describe the situation as follows:

There was presumably a wish that the Sibelius Academy would be taken over by the state with its assets and liabilities; it was obviously an economic matter that one wished to become state-owned and it was also a matter of higher education politics in the 1970s – Sibelius Academy was not the only one, it was the penultimate; Åbo Akademi was the last one. (Student)

Åbo Akademi is a Swedish language university in Finland and it was the last independent university of the reform process. It was a common trend. Private academies had vanished. (Student)

There were two affairs to be executed at the same time: the nationalization [of private academies] and examination reform. It was pointed out that the time was up for a private academy. So these two affairs were considered together, so that without examination reform, a school couldn’t be a state-owned institution. (Administrative assistant)

There were no alternatives, it was a political decision and to the state you will come when you follow the line.

(Administrator)

The interviewees were sure of the pattern: the path was to be followed and it would inevitably lead to the reformation at the end. Furthermore, another administrator comments:

Well, concerning the examination reform, we were forced to make the changes; there was no chance to refuse to conform; we would have become a conservatoire, not an academy. We were forced to take part in the examination reform. (Administrator)

In the conservatoires the vocational education is also given but at an academy level the vocational music education is on higher university level. The Act given by the Government of Finland to reform the degree system of the universities in Finland was a starting point for the renewal. The other motivation behind the reform was that arts colleges should achieve in all ways a position equivalent to what the scientific universities already possessed. Arts colleges had been categorized on a lower vocational education level; they were not covered by the existing legislation of developing universities or the Finnish Higher Education Evaluation Council. The Council Members represented universities, universities of applied sciences, students and people in the private sector. Decisions made by the Council were prepared and implemented by the Secretariat, led by the Secretary General. The administration was not the same, and economic resources and appreciation were lower than for the scientific universities respectively.

Launching

The second phase of the reform process can be called launching. The first step towards the examination reform at the Sibelius Academy was taken on 15 February 1975 by the rector by suggesting to the board that the demands of the reform be investigated. At the meeting, the board appointed a committee to prepare for the reform at the Sibelius Academy. In 1977, the reform became official. The role of communication seemed to be one of the most important parts of the launch. The interviewees were asked: When and how did you become aware of the reform?

At that time, in the 1970s, I was studying at the Sibelius Academy. The reform was always on the table. (Student)

The Sibelius Academy published internal information sheets calledand. This was the way to inform the students and personnel at that time on a weekly and monthly basis. The course of the process was described in the document,. A special issue ofwas published with a report on the reform. A questionnaire was used to get feedback from teachers.

I began to wonder where did [the information] come from and if it was a command from upstairs, the committee appointed by the rector. He appointed it after having heard of the reform . . . On the other hand, a professor’s daughter who was involved with the reform on the national level was my student in the 1970s at the Academy and we were friends a long time afterwards. This was perhaps the other channel [by which I learned of the reform], via a student on the one hand, and via the rector on the other. These were my channels of information.

(Teacher, committee member)

Those who were involved with the administration of the reform received information directly from the rector.

One interviewee was working in the administration of the Sibelius Academy in the 1970s. He noted:

The work with the examination reform was introduced at some point in [about]1976 or so, and it had nothing to do with the nationalization of the Sibelius Academy, but at that time 1975-76 or a bit earlier, they began with the science universities and with us we appointed a committee for examination reform that worked for several years and developed models . . . they came from DDR (former Eastern Germany). (Administrator)

We also asked the Interviewees how the reform was introduced and communicated to the personnel. We wanted to know of what the reform would consist and what it would require.

We had meetings together. We received all the information, of course, and the publication Äänenkuljettaja came out every week and if only you read it. Not everyone did, and neither did the students, which is odd; most of the people were passive. One would imagine that the students would be interested in their own exam matters that were presented in Äänenkuljettaja. Overall, arts students showed minor interest in administrative and structural matters, which is surprising. It was all over and you couldn’t miss the information.

He points out that internally the reform was communicated in a satisfactory manner. There were several ways to inform those involved and the information was readily available. One administrative assistant was active with the reform and was one of those delivering information. He describes the situation as follows:

Researcher: Do you think that the personnel were being informed in real time?

Administrative assistant: Well, I was one of those doing the informing. -Was the information open? -Hmm, well, it was as open as it could be; I wouldn’t say that we tried to keep something secret, but, of course, delivering information is always difficult, if you have a goal. Maybe the rector gave an inaccurate picture of the whole situation from the beginning to the end. However, if he had acted differently, we may not have had the result we wished for.

Researcher: Do you mean that the Rector took the teachers’ side?

Administrative assistant: Yes, yes. He said that nothing would be changed, that we would rearrange some matters if it is demanded. So, it was psychologically smart. Yes, altogether, I think it was the only way to get [the reform] through, in spite of the beginning. If it were done today, everything would be done in a totally different way. (Administrative assistant)

This interviewee thinks that the means of communication impacted the way that they were able to get the reform through with the personnel. Another interviewee confirms that the goal was well intended. The teachers were given the possibility to receive information and with their own suggestions to influence the reform. She points out that this met with opposition by the personnel.

Researcher: How did you communicate, give the information about the reform?

Administrator: Well, we tried to keep the personnel as up-to-date as possible and we organized an event where we informed everyone and this was something that was met with resistance that you should sit in a meeting and have suggestions of your own. But I think this was handled well.

Researcher: Altogether, did you get some positive feedback?

Administrator: No, no, on the contrary. Although they got a chance to influence reform Yes, yes, they received notices of the meetings, but this wasn’t good perhaps because the participation of the reform was not real or practical. (Administrator)

All in all, the personnel at the Sibelius Academy were not so interested in the reform. During the launching, the personnel received information, but were interested in neither receiving it nor working on it to influence the reform.

Reactions

At the beginning of the reform process there were many kind of reactions and most of them were not positive ones. Participants were worried and a little bit afraid of what was coming through the reform. One of the interviewees teaching at the Sibelius Academy in the 1970s said:(Teacher) The researchers also asked other questions to explore the various responses that teachers and administrators had to the examination reform.

Researcher: What about resistance to change? Was there any resistance to change?

Teacher: We talked about this during the meetings. What if it will be in a same way as they have it at the faculties of the medicine that you go through a system, courses and a program without practicing your skills enough for the future work.. They are all on a bit different level at the beginning although they all are capable to learn and each of them will mature individually… and what I would like to point out is that they have not reached a proper level of matureness in the school or in a music school, and later in a higher education they should learn many other things than becoming technically perfect. (Teacher)

The teachers were afraid that they and their students would have to take examinations on a timetable that wouldn’t be natural and that they would not be able to determine themselves, if the timetable for studies would be determined by others in the system. Further, the Teacher thinks that you should respect the students as persons and make sure that they can mature at their own individual tempo. To study is not only to study at the academy. Student life is important for a young person to be able to grow up and become an adult. Students mentioned the confrontation between arts and structural thinking that became dominant. The Sibelius Academy had a tradition that promoted artists and practitioners. For this tradition, formal examinations felt strange.

Furthermore, there are professional musicians who have studied at the Sibelius Academy, but they have never accomplished their studies. One teacher stated that arts per se have little to do with formal degrees. He described the new profile with studies so that you put an emphasis on all-round education, and agreed that the time was right for doing so.

Well, we have outstanding musicians, the best ones in Finland, who for twelve years have been at the Academy and developed themselves and given concerts. There are many people who have not accomplished their studies at the Academy--one should not name anyone--but who have nevertheless made a career . . . I only mean that this can be the result when we talk about an artistic academy so it is arts that matter and this has at the end not so much to do with examinations and degrees. Nowadays one tries to train as smart and inventive a musician as possible, who has an all-round education; these days more of such people are needed. (Teacher)

A former teacher and committee member is of the same opinion. He thinks that apprentice learning had reached its peak, a phase that as such did not have a future.

There was a school of thought which considered this way of thinking still relevant and that it was not necessary to bring in new, unfamiliar elements into this system. The other school of thought held that the Sibelius Academy should educate musicians with a high-level, well-rounded education. Earlier it was not thought that such an education was necessary for musicians who were simply practising their profession. You can always wonder afterwards and someone may take offense–isn’t this after all a paradox--that you have the best possible artistic manpower as instructors and couldn’t you just go on with the apprentice learning? You don’t need so broad an education as a professional musician. Then there was this other viewpoint with the prejudice that for a professional musician it would be enough to have a certain skill. The youth at that time asserted that the Academy should not train just one skill, but rather develop a human being as a whole, as in all the other universities. This was the case. (Teacher, who was a Committee member)

The interviewee reports that the personnel were alarmed; the incident raised fear. It was fear of the bureaucracy, and this bureaucracy could appear in different ways. He continues:

It is natural; people don’t think, Oh so nice, a change! They may be afraid or feel threatened.

Researcher: What were they afraid of?

Interviewee: Firstly, because the nationalization was acute at the same time—it was fear of bureaucracy.

It was something that was difficult to define and could mean several things. There is an image of someone who has his or her desk in order: a bureaucrat . . . and when his or her table was a mess, he or she was still a bureaucrat. Both of these images meant that we were working with papers and words and they became the most important part of our work and we produced more and more A4-papers and we thought it meant something important. However, this was demanded by others; outsiders demanded this. However, on the other hand, someone outside the academy demanded all this. Therefore, we also considered it internally whether all this was a necessity.

(Teacher, who was a Committee member)

The interviewee describes that the need for “word and paper” came from outside. Bureaucracy was needed to satisfy the administrative needs outside the Academy. At the same time, he points out that someone at the Sibelius Academy over emphasized this need in two ways: quantity and significance. At the Academy, it was soon clear that there was an outer need to mediate information to the state administration and this fact created and motivated this need internally within the Sibelius Academy.

Become committed

How did one meet the resistance to change, motivate different actors and make them feel as an integral part of the change? A person working with the reform in the 1970s stated:. (Administrator)

Another interviewee who describes reasons for resistance confirms what we had earlier learned. We discussed resistance to change and doctoral degrees and noted that the other universities did not accept the fact immediately as that this would mean that the Sibelius Academy had the same status that they already had. Another administrator reports:.

(Administrative person, Committee member)

The examination reform acted as an inspiration for one of the interviewees. He composed a work that describes the sequence of events and the reactions it raised in a thoughtful manner. (Administrative person, Committee member)

Motivating actors ahead of a change is done through communication, but there are even other ways to motivate.

The question was put separately to avoid preconceptions from my side.

Researcher: Were the teachers motivated ahead of the reform? In what way?

Teacher: Well, one tried to brainwash a bit with objective information for the most part. It sounded like, ‘My friends, we know how capable you are; you have been like that earlier and you still are like that, and now we have to change some labels so that it would appear a bit better and we are going to present such and such an idea. It looks nice, doesn’t it? It was a bit the way a businessperson would persuade someone.

The command was actually the fact you just said that we cannot let the Academy go bankrupt and halve all the salaries, or can we? That doesn’t sound good or (laughs) . . . and it went through; there was no trouble. (Teacher)

The interviewee describes that one was motivated through communication. One expressed oneself in a way that gave a perception that the reform only was a cosmetic thing, a change of clothes, a renaming of some things, but it would not touch the very heart of the operative work. At the same time, there was an understanding given that the reform was the only way to find solutions to problems the Academy was facing.

A teacher at that time describes how one appealed to all the actors at the Academy over the future of the Sibelius Academy.

It was very much in the limelight everywhere that the whole Academy had to come along. Absolutely. Everyone was made to feel that is was in the Academy’s best interest, and in the students’ interest. The future of everyone seemed to depend on it, but we understood that it was a matter of money, Students were taking too long in their studies and, the state wanted to have better control, because it is the state that picks up the bill. (Teacher)

A former student also emphasised communication as a motivating factor. The employees were offered information at the meetings and that also gave them an opportunity to influence change.

At that time, the way of thinking wasn’t at all so democratic; one made a decision that seemed to be necessary and one didn’t think that it was necessary to ask teachers’ opinions all the time. Besides, the time was totally right for change; it was clear that a private academy like SA did not realistically have a future. Once they were aware of this fact, people became committed. (Student)

In other words, it was clearly communicated that these reforms were necessary in order to secure the future of the Sibelius Academy. The reform was the only solution; one wanted to assure the personnel and the students of the necessity of the reform. A teacher described this point in much detail:

You can imagine that the situation was a new one. The rector was personally very vigorously engaged with the case and he had an understanding of both points of view; he understood that he had the responsibility to develop the Sibelius Academy, but he also understood the pride of the artist, that this had to be enough. So, it became a compromise, so to speak, that the Sibelius Academy had to be developed as an academy because the arts are not less worthy than the sciences and it is not about academic marks or degrees or bachelor’s, master’s, licentiate, or doctor’s degrees; it was not about their contents, but the level of education. For example, within the sciences a student has the possibility to go through these steps so a student should have the same possibility within the arts to go forward. It doesn’t mean that if you have written a doctoral thesis that you would be a scientist or scientifically-orientated person, but the substance of an artistic work has to be of the same quality as that of a scientific work. These were the starting points; they originated from learning situations in the arts, its special weight, and its teaching methods. (Teacher)

As the history demonstrated, the activity became regulated with acts so that each university would have an act of its own. It would be seen that this had been the right analysis, at the end of the 1990s a common act became law and the universities once and for all have the same status; it was a struggle for rights for the Sibelius Academy. The formal side of this is the right to struggle for permission terms and rights in working life, but if you consider the social psychological situation, so it was so that the time was wrong for such discussion in the future, that two big changes would be ahead. (Teacher, who was a Committee member)

The interviewee considers the context of the examination reform for the Sibelius Academy as a matter of principle and equality. He considers the rector at that time as being a person responsible for the future development of the Sibelius Academy. According to one interviewee the situation within higher education policy was mature for reform. At the same time, the rector was aware of an artist’s pride. A natural question was how the traditional university world with universities of sciences and an emphasis on research on one hand, and the artistic and the practical exercise of arts on the other, would relate to each other. The substance in an artistic piece of work should be of the same quality as the quality of a scientific one. The fact, that one would apply the new terminology and the structures, but at the same time, hold on to the old artistic tradition was not seen very possible in practice. This reform would be a link in a long tradition beginning in the 1960s, going on to the twenty-first century and continuing to the future.

Examination Reform Act 1980

The nationalization (1979) and the examination reform (1980) which occurred practically at the same time at the Sibelius Academy were not dependent on each other. In this research material, five phases of the reform process were found (see Figure 1).

Conclusions and discussion

This historical overview shows that an organizational culture can only completely be experienced by insiders and demands empathy others in order to be appreciated by outsiders (Hofstede et al., 1990). Many researchers (e.g., Pettigrew, Woodman & Cameron, 2001) discuss six interconnected analytical issues when studying organizational change, where the organizational change study literature is not developed enough. We like to put a special emphasis on the first two: the examination of multiple contexts and levels of analysis in studying organizational change, and, secondly, the inclusion of time, history, process, and action (Pettigrew et al., 2001).

This qualitative case study of the examination reform process aims to discover how the decision, which was made to reform the examinations in higher education, was put into practice at the Sibelius Academy. The research problem was to determine the process of the examination reform at the Sibelius Academy from 1974 to 1980. As results, five phases of the reform process were introduced through qualitative interview material. These phases are reasons, launching, reactions, becoming committed, and examination reform. These phases describe how the examination reform was implemented at the Sibelius Academy. Communication was essential in the reform process. The reactions of the people involved with the process were strong when they heard about the reform at the Sibelius Academy. The way the reform was launched and how people were made committed were crucial in the communicative interaction.

In the reform process, the primary task is to organize in order to survive and tackle the challenges in the environment. The Sibelius Academy had to simultaneously meet the organizational and economic requirements set both internally and externally. The design of this artistic organization, thus, needed a consensus of both a great degree of passion and a great deal of logic (Rajala et al., 2012).

Cultural perspectives on organizations emphasize the maintenance of strong organizational cultures as a strategy linked to higher performance and thus point to the conclusion that strategic management in successful organizations usually involves anticipatory adaptation rather than radical change (Peters et al., 1982). According to Johansen (2009), an idea comprising education politics and higher music education as two self-referential but intercommunicative systems has been proposed to avoid the marginalization of those two fields. During the period from 1974-1980 the organizational change at the Sibelius Academy was historical. The authors state that processes during that period and the actions taken were crucial for the survival and the development of higher music education in Finland.

Acknowledgements

The author(s) declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

Chiapello, E. (1998). Artistes versus managers: le management culturel face á la critique artiste. Paris: Editions Métailié.

Daigle, P., & Rouleau, L. (2010). Strategic Plans of Arts Organizations: A Tool of Compromise Between Artistic and Managerial Values. Strategic Management, 12(3), 13-28.

Hofstede, G., Neuijen, B., Ohayv, D. D., & Sanders, G. (1990). Measuring Organizational Cultures: A Qualitative and Quantitative Study across Twenty Cases. Administrative Science Quarterly, 35, 286-316.

Johansen, G. (2009). An Education Politics of the Particular: Promises and Opportunities for the Quality of Higher Music Education. Arts Education Policy Review, 110(4), 33-37.

Jones, P. M. (2009). Hard and Soft Policies in Music Education: Building the Capacity of Teachers to Understand, Study, and Influence Them. Arts Education Policy Review, 110(4), 27-31.

Kos, R. P. Jr. (2010). Developing Capacity for Change: A Policy Analysis for the Music Education Profession. Arts Education Policy Review, 111, 97-104.

Maitlis, S., & Lawrence, T. (2003). Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark: Understanding Failure in Organizational Strategizing. Journal of Management Studies, 40, 109-139.

Peters, T. J., & Waterman, R. H. (1982). In Search of Excellence. New York: Harper & Row.

Pettigrew, A. M., Woodman, R. W., & Cameron, K. S. (2001). Studying organizational change and development: Challenges for future research. Academy of Management Journal, 44(4), 697-713.

Rajala, I., Ruokonen, I., &Ruismäki, H. (2012): Organizational culture and organizational change at Arts universities. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 45, 540-547.

Saunders, M., Lewis, P. R., & Thorndike, A. (2000). Research Methods for Business students. London: Pittman Publishing.

Yin, R. (1994). Case Study Research: Design and Methods. London: Sage Publications.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.