Abstract

One of the most important cultural changes in the 20th century was the rise of identity as a fundamental value. Therefore, it is also important to know how musicians identify themselves in music. The purpose of the study was to ascertain how students training as music teachers (school music pedagogy and interpretation pedagogy) at Estonian Academy of Music and Theatre (EAMT) determine their musical identity and to compare relevant components. How do musical aptitude, home and school environments and personality influence the formation of musical identity? Is the musical aptitude of music and interpretation pedagogy students similar or different? The research was carried out using mixed methods. The data were collected in different ways by using the questionnaire of musical background, the scale of musical identity, Gordon’s test of musical aptitude and personality test Short Five. The research sample consisted of 20 MA students of EAMT. The results revealed that the students of teacher training programme identify their musical identity primarily through educational factors. The only difference in identity building of the mentioned student groups was observed when considering personal and musical aspects. Music pedagogy students prioritize musical factors over personal factors, but interpretation pedagogy students attach equal importance to musical and personal aspects. The results showed that music teacher training programmes create considerably favourable environment for the development of educational factors of future teachers’ musical identity and do not take so much notice of the musical components of musical identity.

Keywords:

Introduction

Music plays a bigger part in the everyday lives of more people than at any time in the past. The rapid development of technology has given people diverse choices how to experience music (as listener, “consumer”, composer, arranger, performer). Music is an important channel of communication that gives opportunities to share emotions, intentions and meanings even if the spoken languages are different (Hargreaves, Miell, & MacDonald, 2002). Making music is mainly a social activity: it is something we do along with and for others. Therefore, one of the primary functions of music is to construct and develop individual’s sense of identity and the concept of musical identity enables us to look at the widespread and varied interactions between an individual and music.

The purpose of this research is to identify how students training as music teachers (school music pedagogy and interpretation pedagogy) at EAMT determine their musical identity and to compare relevant components.

Theoretical background

An interest in human beings and their inner world increased in the 1970s and the problems of identity became more evident. Freedom, changes, multiplicity of options – all those describe the current society of Estonia, therefore, problems of identity are still relevant (Valk, 2003). The significance of music in individual’s everyday life is continuously growing and that is why it is important to study musical identity.

Individuals deal with their identity and identification of themselves all the time without even noticing it. Therefore, identity is so inherent to every individual that it is not necessary to acknowledge it in every situation. The essence of human psychology is complex. There are many different theories of identity that observe the identification of individuals. In this study identity is seen as a firm, constant and associated conception at certain time (Valk, 2003). On the other hand, multiplicity and uncertainty of identity characterise society, and therefore, if necessary, individuals may identify themselves differently (Erikson, 1968). Identification includes demeanours inherent in individuals and is used in communicating with others. Individuals play a crucial part in identifying themselves because the identity is affected by individual’s unique nature and experiences and also by social relationships and belonging to social groups. Therefore, identity is realized only when individuals are facing new situations and knowledge. Old experiences are reviewed and after interpreting those, new identity is created. Since everyone wants to be recognized as an individual and as a person, and wants to belong in a specific group, it is possible to distinguish between personal and social identity that at the same time influence and depend on each other (Baumeister, 2011; James, 1952; Mead, 1934; Valk, 2003).

Music plays a great part in our daily life. In everyday life the role of music is to create an identity, shape the surroundings and influence the state of mind of a human (Rüütel & Kask, 2004). Individuals use music to develop and organize the relations between each other, and their musical preferences show to which social group they belong. Music defines belonging to a specific sociocultural environment; it is a part of lifestyle and one of the most important expressions of lifestyle. Music is listened while engaging with other activities, for relaxation, and music is also used for transferring emotions, therefore, it is possible to talk about musical identity. Individuals define themselves in music using culturally and socially defined roles, while being a performer or simply a listener. Professional musicians use music mainly to develop their personal identity. Musical identity is the perception of individual’s musical self and it is in constant change (Talbot, 2013). The main influencers of musical identity are social and cultural environments that surround an individual. School and home environments that influence individual’s motivation and musical ability, play a great part in the development of musical identity. The role of favourable surroundings is important already at an early age because the higher musical ability of a child by the ages of nine gives the child better potential to feel her or himself musically gifted. Therefore, it gives the child steadier and stronger musical identity (Gordon, 1989; 2001).

Higher education offers an environment where future teachers acquire all their basic knowledge about teaching. The development from a student into a teacher is a process of many years and teacher-training programme is the launcher of it. University is the place where many pedagogical, subject-related and psychological attitudes, values and skills are developed. Many researchers (Cooper & He, 2012; Krzywacki, 2005) outline that one of the most important tasks of teacher-training programmes is to support the future students and to create the necessary environment for their versatile development. Therefore, teacher-training programmes should pay attention to the secure environment that would give potential teachers a model to imitate (Korthagen, 2004).

The teacher-training programme at EAMT is offered by two institutes: the Institute of School Music that educates future school music teachers and the Institute of Interpretation Pedagogy that trains instrument teachers for music schools and music classes. The curricula of music and interpretation pedagogy are versatile. The institutions offer different musical, didactic, psychological and other subjects. Although the curriculum of interpretation pedagogy has musically more active subjects, the students who enter the master programme of music pedagogy need to have a bachelor’s degree in music. As an outcome, both curricula bring out not only musical and pedagogical knowledge but also didactic and social competence (Estonian Academy of Music and Theatre homepage, 2014).

Research Questions

All the above refers to the research questions:

1. How do future students identify themselves musically?

2. How do home and school environments influence the formation of musical identity?

3. Is the musical aptitude of music and interpretation pedagogy students similar or different?

3.1. Is there a connection between early instrument learning and musical potential?

4. What are the connections between future teachers’ musical identity and personality?

Research Methods and Process

Survey research was carried out using mixed methods. The data were collected in different ways by using: a) the questionnaire of musical background, b) the scale of musical identity, c) Gordon’s test of musical aptitude (Gordon, 1989), d) personality test Short Five (Konstabel, Lönnqvist, Walkowitz, Konstabel, & Verkasalo, 2012). The scale of musical identity consisted of 40 statements that were equally divided into four categories: musical, educational, personal and social components.

The questionnaire of musical background, the scale of musical identity and personality test S5 were filled in by the respondents on the Internet. The participants completed the tests when they had an opportunity. Gordon’s test of musical aptitude was carried out in Estonian Academy of Music and Theatre. The tests on the web were assembled into a table and the results of musical aptitude were added. To find correlations between the tests and the questions, the data was analysed using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. T-test was used for comparative analysis between music and interpretation pedagogy students but unfortunately statistically significant differences were not found.

The sample consisted of 20 EAMT master degree students: 10 school music pedagogy and 10 interpretation pedagogy students.

Result

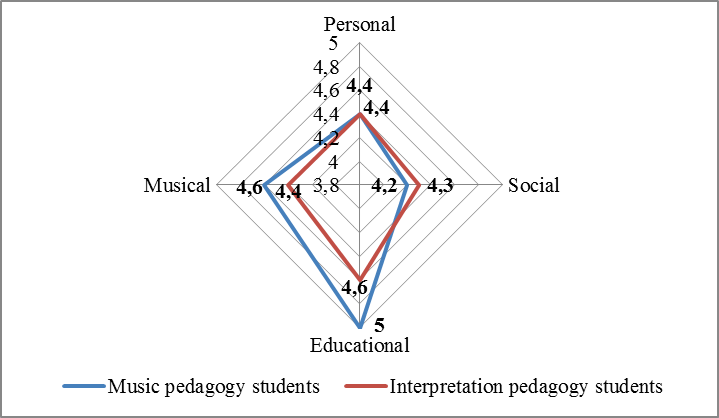

According to the results, the musical identity of music pedagogy students was to some extent predictable. Figure 1 describes the mean results of musical identity scale.

Music pedagogy students prioritize educational factors over musical components. The difference between personal and social components was not so clearly revealed. The musical identification of interpretation pedagogy students was rather surprising. It was expected that future instrument teachers acknowledge mostly musical components, but the results revealed that they also prioritize educational factors of musical identity. The most surprising finding was that interpretation pedagogy students attach equal importance to musical and personal aspects. Instrument teachers least identify themselves through social factors. It can be concluded that according to the results, the musical identity of music pedagogy students is slightly stronger than the musical identity of interpretation pedagogy students.

An analysis of the home and learning environments of the respondents revealed that while their home environment has been beneficial to the development of their musical identity, there were no statistically significant connections between home environment and the aspects of musical identity scale. Therefore, the results of this study do not confirm direct influence of home environment on the musical identity of future teachers. The results showed that music pedagogy students and interpretation pedagogy students have both had a similar home environment. Parents’ musical education showed the biggest differences between the two groups. There was also a positive weak correlation (p = .045) between the home environment and parents’ musical education of interpretation pedagogy students.

Music and interpretation pedagogy students most prioritize educational factors in their musical identity and both groups acknowledge positive model in learning environment while choosing their profession. This suggests that learning environment has influenced the musical identity of future teachers. The results of music pedagogy students showed a weak positive correlation (p = .038) between musical aptitude and educational aspects of musical identity scale.

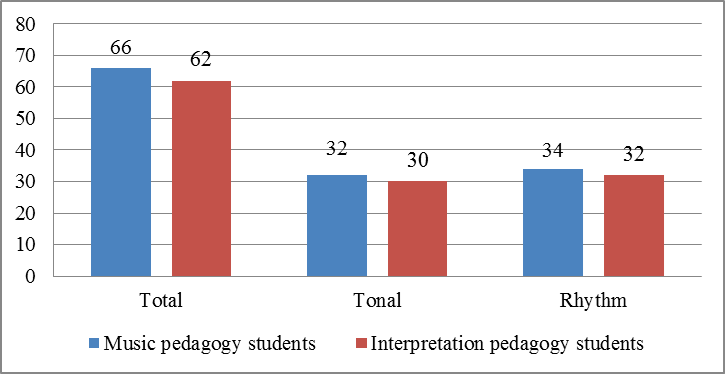

The musical aptitude of music and interpretation students is rather similar because the differences between the scores were small (Figure 2).

The results show that the musical aptitude of music pedagogy students is slightly higher than interpretation pedagogy students. Although rather small differences were observed between the scores, music pedagogy students have higher mean scores in every parameter (total, tonal, rhythm). The results of musical aptitude test also show that there are some musically very gifted students among the future music teachers. Therefore, the results of music and interpretation pedagogy students would be quite the same if there were not some musically outstanding students among music pedagogy students.

According to the results of musical aptitude and early instrument learning it was revealed that music pedagogy students have higher scores in Gordon’s test (Figure 2) and they have also started learning their first instrument earlier (on average, at the age of 5.5 years) than interpretation pedagogy students (on average, at the age of 8.2 years). Unfortunately, there were no correlations, and therefore this data could not be used to confirm the influence between early instrument learning and musical potential.

This study also researched if there are any connections between musical identity and personality. The analysis between the parts of personality test (neuroticism, extraversion, openness to experience, conscientiousness, agreeableness) and the aspects of musical identity scale revealed positive correlations only in two cases: between musical components and agreeableness (p = .029) and between social aspects and extraversion (p = .022). The results of the personality test do not show remarkable differences between the two groups. It was also expected because both professions are similar and require similar characteristics. The biggest differences between music and interpretation pedagogy students occurred at an equal extent in extraversion and in conscientiousness. The connections in two groups apart appeared only once – the results of interpretation pedagogy students showed a positive weak correlation (p = .042) between musical components and agreeableness. It can be concluded that according to this study the connection between musical identity and personality is rather weak.

Discussion and conclusions

The results of this study show clearly that the musical identity of both, music and interpretation pedagogy students, is mainly based on educational factors. Therefore, it is possible to speculate – curricula that support the development of pedagogical basic skills have helped to form quite strong pedagogical identification in future teachers. It is also possible to assume that the Estonian society primarily prioritizes pedagogical competence of music and instrument teachers over their musical skills. In particular, this opinion shows the attitude towards school music teachers who mostly are acknowledged as teachers not as musicians.

The results also revealed a strong connection between personal and social components of musical identity and it is evident because it is not possible to look at personal and social identity apart from each other. The institutions that offer teacher-training programmes should therefore take notice of different teaching methods (seminars, teamwork etc.) that would help to develop the social skills and thereby personal attitudes of their students.

The analysis of student’s home environment showed that almost all future teachers were surrounded by singing and instrument playing in their childhood. Therefore, the positive musical environment in childhood gave the respondents the best conditions for pleasant contact with music. Since 18 homes out of 20 had musical instruments, it can be speculated that because of the instruments the respondents had also good conditions for developing their musical identity. One of the influencer of musical identity is learning environment. The results of musical identity scale showed that musical identity is influenced mostly by educational factors. Educational aspects are closely connected with school and teaching, therefore, it can be said that learning environment has to some extent affected future teachers’ musical identity. The results revealed that the musical components of musical identity are connected with the respondents’ social and personal identity. Accordingly, music education in Estonia encourages the development of the components of musical identity and helps to shape the personal and social identity. The analysis of students’ home and learning environments showed that the students have had favourable surroundings for versatile development and expression. Home musical environment in childhood has presumably given future teachers different experiences as listeners and performers. Learning environments have certainly enriched students with experiences that have offered opportunities to perform and introduced the profession of a teacher.

Teacher-training programmes could not be certain that the music education offered also ensures the effective development of educational aspects of students’ musical identity. The results showed that the future teachers determine their musical identity primarily through educational factors. Therefore, teacher-training programmes do create a considerably favourable environment for students’ pedagogical development. One of the most important identification aspects of music students is music. The results of this study revealed that students consider musical aspects of their musical identity second most important. Therefore, institutions that offer music-teaching programmes at master level should never forget the importance of music, and the curricula of music and interpretation pedagogy need to have balance between musical and pedagogical subjects.

Acknowledgements

The author(s) declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

Baumeister, R. F. (2011). Self and identity: a brief overview of what they are, what they do, and how they work. Annals Of The New York Academy of Science, 1234(1), 48-55. DOI:

Cooper, J. E., & He, Y. (2012). Journey of "Becoming": Secondary Teacher Candidates' Concerns and Struggles. Issues in Teacher Education, 21(1), 89-108.

Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. New York: Norton. Estonian Academy of Music and Theatre homepage. Retrieved on January 13, 2014, from http://ema.edu.ee/index.php?main=280

Gordon, E. E. (1989). Manual for the advanced measures of music audition. Chicago: GIA Publications.

Gordon, E. E. (2001). Music Aptitude and Related Tests: An Introduction. Chicago: GIA Publications.

Hargreaves, D. J., Miell, D., & MacDonald, R. A. R. (2002). What are musical identities, and why are they important? In R. A. R. MacDonald, et al. (Eds.). Musical Identities (pp. 1-20). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

James, W. (1952). The Principles of Psychology. Chicago: Encyclopaedia Britannica.

Konstabel, K., Lönnqvist, J.-E., Walkowitz, G., Konstabel, K. & Verkasalo, M. (2012). Measuring Personality Traits Using Comprehensive Single Items. European Journal of Personality, 26, 13-29. DOI:

Korthagen, F. A. J. (2004). In search of the essence of a good teacher: towards a more holistic approach in teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 20, 77-97. DOI:

Krzywacki, H. (2009). Becoming a teacher: emerging teacher identity in mathematics teacher education. Retrieved on January 7, 2014, from http://www.doria.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/50274/becoming.pdf?sequence=1

Rüütel, E., & Kask, D. (2004). Muusikateraapia [Music Therapy]. In. J. Ross & K. Maimets (Eds.). Mõeldes muusikast: sissevaateid muusikateadusesse (pp. 268-295). Tallinn: Varrak.

Talbot, B. C. (2013). The Music Identity Project. Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education, 12(2), 60-74. Retrieved on January 2, 2014, from http://act.maydaygroup.org/articles/Talbot12_2.pdf

Valk, A. (2003). Identiteet. [Identity]. In J. Allik, A. Realo & K. Konstabel (Eds.), Isiksusepsühholoogia (pp. 227-250). Tartu: Tartu Ülikooli Kirjastus.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.