Abstract

The article presents a new educational design for the subject drama pedagogy in light of the paradigm shift in contemporary theatre towards a postdramatic theatre (Lehmann, 2006). Going out from a historical perspective a basic concept of aesthetic doubling based on dramatic fiction is successively identified as constitutive of the classic subject drama pedagogy. The historical exposition is followed by a brief introduction to the postdramatic theatre by means of the concepts postdrama, theatReality and f(r)iction, which is seen as a hybridization of the classic notion of fiction. Recent examples of postdramatic theatre performances are given, and the outlines of a new educational design for drama and theatre pedagogy inspired by this form of theatre is demonstrated by explanation and examples from educational practice at the Master’s Programme of Theatre Pedagogy at Metropolitan University College Copenhagen. Finally, it is argued with additional reference to Lawrence Grossberg’s (1992) forms of authentic inauthenticity that drama and theatre pedagogy must turn postdramatic in its curricular basis in order to stay relevant for future generations of young people and other target groups.

Keywords: Dramatic curriculum, postdramatic theatre, postdrama

Prologue

This article presents a new educational design for the subject drama pedagogy in light of the paradigm shift in contemporary theatre towards a postdramatic theatre (Lehmann, 2006). Going out from a historical perspective a basic concept of aesthetic doubling based on dramatic fiction is successively identified as constitutive of the classic subject drama pedagogy. The historical exposition is followed by a brief introduction to the postdramatic theatre by means of the concepts postdrama, theatReality and f(r)iction, which is seen as a hybridization of the classic notion of fiction. Recent examples of postdramatic theatre performances are given, and the outlines of a new educational design for drama and theatre pedagogy inspired by this form of theatre is demonstrated by explanation and examples from educational practice at the Master’s Programme of Theatre Pedagogy at Metropolitan University College Copenhagen. Finally, it is argued with additional reference to Lawrence Grossberg’s (1992) forms of authentic inauthenticity that drama and theatre pedagogy must turn postdramatic in its curricular basis in order to stay relevant for future generations of young people and other target groups.

The discipline drama pedagogy, inspired by the reform pedagogical movement in the first half of the 20th century has been a constant battlefield for conflicting views on play, aesthetics, culture and the art form of the dramatic theatre. Thus, Brian Way (1967) and others partly inspired by, partly in opposition to creative dramatics (Ward, 1930) rejected a theatre oriented drama pedagogy. Instead of pursuing artistic mastery, child drama (Slade, 1973) should aim at the development of the whole person: creativity, self-confidence, social skills and a natural sense of aesthetic form through dramatic play. Half a decade later the scene had changed. David Hornbrook was relentless in his critique of the fact that drama finds “its way unto the curriculum less like a subject than a way of promoting social and mental health” (Hornbrook, 1998, p. 10). For Hornbrook (1998) drama is about

cultural induction. We share our knowledge and understanding with students so that they can develop a critical framework within which they can enjoy plays; we share our skills – as directors, actors, designers, playwrights – so that they can practice the art of drama for themselves. (p. 14)

Today the scene is changing again. A variety of forms of postdramatic theatre are gaining momentum – even in mainstream theatre productions – based on non-dramatic ‘states’, non-acting, hybridizised fictions, genres and textscapes, mediation and reorientation of audience-performer relations, de-hierarchization of theatrical means and functions and new, often nomadic and collective production forms (Lehmann, 2006). Such theatrical forms are, measured against the standards of the dramatic theatre, something else than merely ‘more-of-the-same-just-different’. They transform the notion of drama in depth, and by doing so also transform the notion of drama pedagogy.

Our experience after 15 years of practice as (post-graduate) educators of drama pedagogues at all levels of Danish educational and pedagogical institutions is that many drama pedagogues still approach their professional practice with notions firmly rooted in dramatic theatricality, and often it is something of a Copernican Revolution for them to come to experience their discipline from a postdramatic point of view. This article explains why – and how – such a reorientation of drama and theatre pedagogy is possible.

The Postdramatic Turn – what is it?

Hans-Thies Lehmann’s (2006) seminal study of the Postdramatic Theatre is interesting, not only because of its perspective on contemporary theatre, but also because of the way it provides this perspective. ‘Postdramatic’ is not necessarily equivalent to ‘postmodern’, and Lehmann does not explain the notion by any singular definition. Instead he shows us a “panorama ... that opens up under the name of postdramatic theatre. It is concerned with phenomena of a most heterogeneous kind” (Lehmann, 2006, p. 23) Still it has the “aesthetic consequence” that makes it “a new paradigm of postdramatic theatre.” (Lehmann, 2006, p. 24)

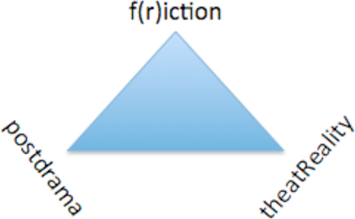

We would like to propose a model that explains the paradigm of postdramatic theatre through three basic principles with relevance for a new understanding of drama pedagogy, each engendering an almost infinite variety of inventions, innovations, variations, metamorphoses, disturbances and deconstructions:

Postdrama

As a prominent figure of the artistic avant-garde Bertolt Brecht worked hard to build his reputation as the Aristotle-antagonist of modern dramaturgy. Brecht disliked what he thought was simplified realism and absorbtion in emotional identification leading to momentary katharsis. However, seen from Lehmann’s postdramatic point of view Brecht’s epic theatre must be understood as a “completion of classical dramaturgy. Brecht’s theory contained a highly traditionalist thesis: the fable (story) remained the sine qua non for him.” (Lehmann, 2006, p. 33) Interrelation between a deep-structure (mythos/fabula) and a causally coherent surface-structure (sjuzhet) is not only constitutive of the ‘well-made’ Aristotelian drama but also of Brechtian epic theatre with its reliance on allegory and distancing effects. The postdramatic theatre parts ways with Aristotle, but it doesn’t always blankly reject any fabula-sjuzhet construct. Instead, it frequently subverts, deconstructs, mocks, simulates or fools around with it. Sometimes though, there will be no plot, perhaps not even action, which is the innermost meaning of the Aristotelian notion of ‘drama’.

TheatReality

Lehmann’s coining of the concept of the theatReal obviously echoes the well known idea of theatricality of the avant-garde movements at the beginning of the 20c. As Erika Fischer-Lichte (1995) points out the notion was on the one hand restricted

“to a particular art form which ... was defined by its very material as essentially different from the material of any other art form. On the other hand, the same movements claimed to close the gap between art and life and to fuse theatre and reality.” (p. 86)

Theatricalization revitalizes the old theatrum mundi metaphor, which demasks reality as profoundly phantasmatic. The theatReal, however works the other way around, or as Lehmann (2006) says with reference to postdramatic images of the body:

“The impulse of postdramatic theatre to realize intensified presence (‘epiphany’) of the human body [points] to the reality that exists only in the theatre, namely the theatrical reality (das TheatReale).” (p. 163)

The intensified presence is effected by a variety of means in postdramatic theatre ranging from non- acting and autobiographic presence to the presentation of documentary or scientific material on stage etc.

F(r)iction

By introducing the notion of f(r)iction we will – inspired by literary theorist Poul Behrendt (2010) – attempt at making our own contribution to a theory of postdramatic drama and theatre pedagogy. Classic drama pedagogy is axiomatically affiliated with the mode of fiction. What small children engaged in a free role play and secondary school students involved in an ambitious staging of Oedipus Rex have in common is that their enterprise relies on a fiction contract which transmutes their real bodies and selves into a doubled representation. Most forms of classic drama pedagogy owe their theories of ‘personal growth’ (Way, 1967; Slade, 1973), ‘gut level of understanding’ (Heathcote & Bolton, 1995) or ‘cultural induction’ (Hornbrook, 1998) to this aesthetic doubling whereby a real self is separated from a fictitious. The aesthetic doubling is the motor of reflection, development and learning in dramatic representation. But theatReal bodies don’t rest safely in a classic fiction contract. Instead, they are propelled by the tension or oscillation between a real presence and a fictitous framing. From this it follows without further ado that such representations should not be confused with realism. One could hypothesize here over the affinities to Hal Foster’s actual bodies and social sites in The Return of the Real, e.g. when he describes how photographic “superrealism derealizes the real with simulacral effects” (Foster, 1996, p. 142). Playing with the real puts the mode of fiction involved in the aethetic doubling in a state of enhanced suspension. We designate this hybridization of the mode of representation with the notion of f(r)iction, a term we have adopted from Behrendt (2010), who borrowed it from Swedish novelist P.O. Enqvist.

“Ni hao Nuuk” and “COSMOS+”

To exemplify we will shortly mention two recent postdramatic theatre productions. Their directors have both been teaching courses with material directly relating to the performances at the Master’s Programme of Theatre Pedagogy at the Metropolitan University College Copenhagen.

Ditte Maria Bjerg’s multimedia performance about Greenland, Ni hao Nuuk (Hello, Nuuk) produced by her own company Glōbäl Stórieš, stages the audience in a post-colonial expedition, wandering between stations that also function as art installations before the beginning of the show. The indoor exhibition-scenography consists of tents, exhibition cases with artifacts from Greenland, video monitors showing Danish and American entrepreneurs, administrators, troops and educators in Greenland, a gigantic cut out, wooden map of Greenland spread out on the floor with an adjacent model of the Kvane Mountain, both being used as stages during the show. The play has no plot line, but undfolds a series of situations relating to the economically and politically sensitive subject of uranium mining. We attend performance lectures by a dwarf actor playing the double roles of an Australian Ph.D., who works as a manipulative lobbyist for a Chinese mining company in Greenland, but also as a most charming panda bear given by the Chinese government as a gift to the people of Greenland.

At other times we listen to autobiographical stories told in the manner of traditional Greenlandic story tellers by a very pro Greenlandic actor, who is presented to the audience as one of Greenland’s globally oriented young people presently working at a major German theatre, and we meet his Danish collegue, who quite openly expresses an embarrassing ignorance about Greenlandic issues on behalf of the Danish audience present. A number of young Greenlandic students in Copenhagen play young Greenlanders in Copenhagen and engage in conversation with the audience about doubts and taboos about Greenland. The show constantly changes between theatrical fiction, storytelling, lecture performance, theatReal dialogue, art exhibition and a perfectly real souvenir shop and café.

The idea of the map of Greenland and the video sequences had been developed and explored by Ditte Maria Bjerg together with the students from the Master’s programme in a course that coincided with the production phase of the performance. This reversal of the order of sequence between production process and pedagogical work, where pedagogy is no longer seen as posterior Vermittlung but as a part of an artistic production strategy bears the mark of a postdramatic approach, both to theatre production and pedagogy.

Performance artist Kirsten Dehlholm and Hotel pro Forma belong to Hans-Thies Lehmann’s Panorama of postdramatic theatre and have for 30 years worked in the borderlands between the visual arts, theatre, technology and science. The Master’s Programme of Theatre Pedagogy is fortunate to have Kirsten Dehlholm as a regular guest teacher, where she generously shares her performance concepts, methods and not least her fascinating work discipline. With Kirsten Dehlholm art and pedagogy amalgamate in an almost magical way, because she knows the art of developing a pedagogical approach from an artistic material. So, Dehlholm does not ‘teach’ drama pedagogy, she performs it as art while working as a performance director with the students.

The performance COSMOS+ delivered the material for one of her courses. Hotel Pro Forma (2015):

Why did Hotel Pro Forma create the performance COSMOS+? Because we are fascinated by the phenomena in the universe. Because we want to create an experience for children and adults where science mingles with art in a large, international format. Because our ambition is that at least two boys and girls from tonight’s audience are inspired by the performance to decide to become scientists ... COSMOS+ explores the discoveries of natural science and the latest images ... With sensory series of images we interpret factual documentation of the phenomena of the universe. Children’s drawings, animated sequences and magic light are other effects used.

The course subsequently inspired students to create a public conference on Theatre Pedagogy and the Sciences, where performance workshops in math, physics and sexology etc. were given along with lecture-performances and plenary discussions. The workshop on sexology was later repeated with the teaching staff in a public school in Copenhagen as part of a course in inclusive pedagogy.

Towards a Postdramatic drama pedagogy

Not each and every trend in contemporary theatre is per se of equal interest in a drama pedagogical perspective, and when we so strongly advocate a postdramatic turn of our discipline we should also ask ourselves how we legitimize our enterprise.

Before doing so, we will present a classic model of reflection through drama and theatre. The model was introduced in a Danish context by Szaktowski (1985). The title not only alludes to the drama-for-understanding program of the Newcastle School, but also to Szatkowski’s own emancipatory perspective: “We have the possiblity of an emancipation, and this possibility is among other things retained and worked out in aesthetic expressions.” (Szatkowski, 1985, p. 137) Heathcote and Bolton incorporate elements of dramaturgy in dramatic play to effect ‘gut level understanding’ through identification and modification. For Hornbrook, the purpose is rather to embrace “the whole field of drama, allowing students to sample and engage with its diverse forms in ways which establish an appropriate balance between a knowledge of drama and the mastery of its practices.” (Hornbrook, 1998, p. 9) Heathcote and Bolton see drama as a tool for thematic learning, for Hornbrook themes are tools for learning about theatre as a form of cultural expression. Szatkowski, however, stresses the emancipatory potential in “collective processes of exploration whose main activity is the use of an improvised fiction that arises when two or more participants – in a shared space – produce ‘as if’-actions using their bodies and voices.” (Szatkowski, 1985, p. 142) In spite of the variety of goals and purposes here, Szatkowski’s model of reflection through drama points to a common fictional basis for understanding and learning in all of these programmes.

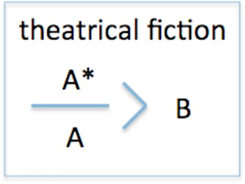

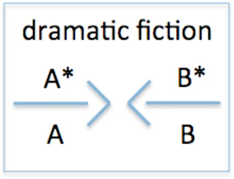

According to Szatkowski theatrical fiction as a minumum involves a performer A, who performs the role A* in front of a spectator B (figure 5). A model of dramatic fiction builds on the theatrical model, but stresses the collective aspect (figure 6).

This doesn’t make the spectator disappear. Instead spectating becomes a kind of participatory reflection:

“[The] moment when B gives life to his character, A in principle for a moment becomes an observant, a spectator the fiction. But as the person, who is performing the character A*, she will also be present in the fiction..” (Szatkowski, 1985, p. 143, our translation)

Whatever the learning goals and purposes are, the reflective basis lies in the dialectic mediation of real actors and fictive characters and real observers and fictive observers. The point of this model of aesthetic doubling is that it is not only A, but also the character portrayed: A* who observes, reflects and perchance learns.

This model cannot account for the reconfiguration of the modes of reality and fiction that occur in theatReal forms of representation. Firstly, the model is not descriptive of what takes place in postdramatic acting, secondly it also doesn’t provide an adequate explanation of the process of reflection involved in such processes. In. Hentschel (2008) succintly explains the notion of reflection involved in postdramatic theatre pedagogy:

“It is crucial that the actor is aware of the simultaneous existence of one and the other. In other words, it is not only about the perception of the double existence but about the perception of the difference between the two levels of reality in the first place.” (p. 6)

The level of meta-reflection described here is achieved in states of acting that go beyond simple ‘as-if’-acting. Hentschel (2008) reformulates Lehmann’s notion of theatReality, thereby stressing that the notion of reality should be understood “in the sense of a societal approach ... and not as an essentially or objectively described world of facts.” (p. 1) This reality results from the use of artifacts, props and projections etc., but also from the way in which the actor is present and uses his body and speech. Otakar Zich’s (1931) three level model of the actor, here referred to from Eigtved (2007), can be used to explain how this can happen. The first level is the actor as he appears on stage as a physical presence (age, sex etc.); the second level is the stage figure where the appearence of a person is created by the use of “technique and behaviour” (Eigtved, 2007, p. 42 (our translation)); and thirdly the character arises as the combined product of the two first. Using this model on the level of postdramatic aesthetic reflection, reality is not predicative of the actor as opposed to the ‘as if’-fictionality of the character. Instead, reality results from a mode of employment of the means of acting on the level of the stage figure, where the actor may eventually even portray himself as non-actor.

Social and cultural theorists have described trends, forms of everyday culture, asthetic practices, values and norms in many of the traditional target groups of drama pedagogy. In Scandinavia these are first and foremost children and young people, but other groups such as elderly people, people with disabilities, managers and communicators in private enterprises and organisations such as the LGBT community are now being targeted by drama pedagogues. All of these groups along with others have recently been worked with in student projects at the Master’s Programme. However, such a widening of the scope quickly becomes a challenge with regard to the didactic design of the education. In short, the answer is to device a curriculum based on carefully cohering macro-, meso- and micro levels (Jepperson & Meyer, 2011). As an example we will mention how we employ the training method known as Viewpoints (Bogart & Landau, 2005) because it scaffolds a multiplicity of learning objectives such as basic physical and movement training, acting technique, spatial awareness, principles of composition and dramaturgy, but also pedagogical aspects such as the development of a sense of one’s capabilities, limitations and zones of development as well as the ability to function in groups and contribute to collaborative creative processes. An additional force on the micro-level of the Viewpoints program is that it allows for high degrees of differentiation of teaching and learning levels, which is important in groups with students coming from different backgrounds in theatre, pedagogy and education. Finally, there is a high transfer potential in Viewpoints, and the practices are easily adaptable to different target groups and purposes.

The aesthetical, technical and pedagogical principles behind Viewpoints are converging well with higher level theories such as Cultural Studies (Grossberg, 1992) and modernization theories (Giddens, 1991; Ziehe, 1983). Such theories help us understand how different target groups reflect and relate to cultural and societal trends that shape everyday life. And indeed, they also indicate reasons for the postdramatic turn in drama pedagogy, not just a traditional drama pedagogy spiced up with avant garde distancing effects, but a relocation to the postdramatic paradigm. Phenomena such as cultural liberation, indvidualization, informalization and subjectivization (Ziehe, 1983) as well as narrative identity formation, reflexivity, doubt and ambivalence, risk awareness and personal meaninglessness (Giddens, 1991) all boil down to an anti-essentialistic morphology, which is in alignment with the postdramatic turn. Gossberg’s (1992) notion of authentic inauthenticity directs our attention to other aspects – also humourous – of such forms:

“The senibility of postmodernity defines a logic of “ironic nihilism” or “authentic inauthenticity” (not to be confused with inauthentic authenticity)It marks the collapse, or at least the irrelevance of the difference between the authentic and the inauthentic. It signals the abscence of alternative spaces: we are all in the same space, already coopted. There are real and important differences within the possibilites of authentic inauthenticity ... I want to distinguish four such variants (although there may be more): ironic, sentimental, hyperreal and grotesque inauthenticity.” (pp. 224, 227)

Dominating styles in contemporary youth cultures such as irony (emotionally investing oneself in the investment itself), sentimentalism (uplifting day-to-day trivialities to ‘freeze frame’ idyllism), hyperrealism (cynical rationalism) and grotesque (life as disproportionate alienation, destruction and horror) show that these cultures are characterized more by affect than by reason or ideology, and through such affective framings the peculiar mode of authentic inauthenticity is brought about. They describe what is going on in music culture and (reality) tv, but also in everyday behaviour of young people that tend to cause insecurity and worry among educators: distancing ways of relating, arrogant vulnerability, nervous coolness, pathetic superficiality and cynical truth-seeking.

Much postdramatic theatre and performance theatre share this celebration (a favourite word of Grossberg) of authentic inauthenticity whose forms could perhaps also be seen as genres of postdramatic theatre pedagogical production. A challenge for theatre pedagogues working with young people today is how to engage the participants fuelled by such energies and forms of expression within our – sometimes much too – well ordered pedagogical and educational institutions.

Luckily, there is not just one single but many answers to this challenge. In the following we will mention two examples from students projects from our Master’s Programme of Theatre Pedagogy.

Staging Life Stories – from C:NTACT to “My Performance”

The Master’s Programme not only involves directors and lighting designers etc. as lecturers, it is also based on a partnership with C:NTACT, a well known Danish theatre project standing with one leg in the field of youth culture and the other in a close cooperation with Betty Nansen Teatret. The students have internships in C:NTACT/Betty Nansen Teatret, and they recieve meticulous theoretical/practial training in the unique C:NTACT-method of staging life stories with non- professional actors, not least young people with an ethnic minority background. The productions, that are sometimes presented on a pro stage as well as in schools and other institutions, live up to high artistic standards. In some cases productions with a mixed cast of professional and non- professional actors are done in cooperation with Betty Nansen Teatret.

The experiences gained in such internships and training programmes along with other modules gradually enable the students to develop – and realize – more radically hybriditzised postdramatic projects, also sometimes based on performative life stories. One such project is My Performance, a performance theatre based, social intervention project with different groups of socially vulnerable citizens. The concept is developed by Katrine Friis and Charlotte Olling Rebsdorf as their master’s project. has also been granted funding for production in a large municipality in Jutland. From the project description:

“Background

What happens in the meeting between to strangers if their mouths are closed, their eyes are vigilant and ears are wide open? A life lived, someone’s life – fragments of dreams, joys, secrets, fear and music. Will that make people talk to each other? Will such meetings break down prejudices and help us get under the skin of others and ourselves? ....

The performance universe

The performance takes place in the everyday environment of the performers. Each performer has his/her own installation, which the spectators visit one after the other. Performer and spectator sit next to each other, both are wearing head-sets. No words between them, only the shared soundscape in the headsets and a box with objects covered with sand unite them. Sound recordings, video sequences, text bites on scraps of paper, and songs open up a space of intimacy, where secrets disclose themselves, favourite songs are choreographed, small joys of everyday life pop up, dreams are revealed and the face of anxiety appears. When all performers have finished the spectators visit a new installation, and a new meeting takes its beginning.” (Friis & Rebsdorf, 2015)

The elements of theatReality in this performance concept are quite obvious. No overall plot-line connects the meetings between performers and spectators. No performance event is simultaneously percieved by the audience, and the spectators are cast and staged just as much as the performers. Thus, the defining feature of the traditional theatrical event: that it involves a live meeting between actors and audience catalyzed by dramatic fiction is here transposed to a theatReal event.

As a theatre pedagogical project, My Performance could be understood as a form of applied performance theatre, or as a social pedagogical intervention mediated through performance and human specific theatre. Friis and Rebsdorf are fully aware of the fact that the majority of participants, some of which are potentially very socially vulnerable, are not likely to be familiar with the conventions of performance theatre. Here, the method of how to develop a personal narrative in a safe and respectful process developed at C:NTACT is given a postdramatic twist through the narrative use of artifacts instead of words only and cast spectators instead of a random audience.

In Real Life (IRL)

During her studies at the Master’s Programme Sine Sværdborg happened to see a performance at ZeBu, a children and young people’s theatre in Copenhagen. The production was based on a new theatre concept called The IRL Method (in real life). Enchanted by the performance, Sine on her own initiative started to develop a method whereby the IRL method could be transformed into a theatre pedagogical method. Sine obtained funding from ZeBu, where she now works as a project manager and theatre pedagogue. The development of the IRL theatre pedagogical method, which at the present moment has been practiced with hundreds of students and teachers from primary school to gymnasium level, also became the subject of Sine Sværdborg’s master’s thesis:

“The IRL (in real life)-method is a new way in which theatre can be seen. With IRL theatre is seen a system. The system consists of four ground rules, and it has no manuscript.

- The magic of now: No agreements are more important than the exchange in the moment.

- No fourth wall: The audience must be seen and heard – it is part of the theatre system.

- Reality is always different: Mistakes must not be hidden or corrected, but exploited.

- Conflict creates consciousness: The exchange occurs by pursuing the conflict. To work with IRL, you have to choose a basic theme from which you start. You set the rules for each course in accordance with its basic theme ...

The IRL method does not target a particular way of working with theatre. The IRL method is a way you can see theatre as a system under which it is possible to integrate most forms of classical and postmodern theatre, as long as you stick to the four dogmas. The IRL method is, in its systemic thinking, a way to reduce complexity. And IRL can, by working with aesthetic learning processes, be a way for the young people to learn about themselves. Also, it can be a way to develop young peoples identities and social and cultural understanding of themselves in a complex society.” (Sværdborg, 2012, p. 2)

IRL is not based on story telling and also not on performance theatre. Outwardly, it bears more resemblance to epic theatre and other forms of re-theatricalized theatre. Also, it is performed as a singular performance event in front of a classic crowd of spectators. Yet it is totally different. There is no a priori underlying dramaturgy, only a set of ‘dogma rules’ that willingly lends itself to any form of theatre. Further, there is no fixed method for working with the participants, only a few high level game rules that open up to magic as well as reality and consciousness. Magic is participation in a collaborative, performative realization of a thematic material, real are the possible autobiographical elements the actors bring into the play, but also the undeniable reality of what actually happens on stage and how it happens. This ‘what actually’ and ‘how’ make the aesthetic doubling more akin to the postdramatic form of reflection on the level of the scene figure. Something similar is at play in My Performance where authentic meetings based on f(r)iction enable in-depth autobiographical exploration and an inquiry of non-fictional aspects of our social environment.

Theatrical interactions such as these with real identites and other elements of theatReality cannot be grasped by the classic fiction contract and its corresponding notion of an aesthetic doubling. Instead they call for a postdramatic turn of the curricular basis of drama and theatre pedagogy – if they want to stay relevant for future generations of young people and other target groups.

Acknowledgements

The author(s) declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

Behrendt, P. (2010). Dobbeltkontrakten didaktisk anvendt – førstegangslæseren i kunst, kritik og klasserum. In J. Fogt, & T. Thurah (Eds.), Ny litteraturdidaktik. København: Gyldendal.

Bogart, A., & Landau, T. (2005). The Viewpoints Book. A Practical Guide to Viewpoints and Composition. New York, NY: Theatre Communications Group.

Conner, L. (2008). In and Out of the Dark: A Theory of Audience Behavior from Sophocles to Spoken Word. In Ivey, William & Tepper, Steven (Eds.). Engaging Art: The Next Great Transformation of America’s Cultural Life. New York, NY: Routledge

Fischer-Lichte, E. (1995). I — Theatricality Introduction: Theatricality: A Key Concept in Theatre and Cultural Studies. In Theatre Research International, 20, 85-89. DOI:

Foster, H. (1996). The Return of the Real: The Avant-garde at the End of the Century. Massachusetts: Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Friis, K., & Rebsdorf, C. O. (2015). Projektbeskrivelse. Min Forestilling – Performative møder mellem to verdener. Retrieved from www.zebu.nu/wp- content/uploads/2015/01/Projektbeskrivelse-min-forestilling.pdf.

Giddens, A. (1991). Modernity and Self-Identity. Self and Society in the Late Modern Age. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Grossberg, L. (1992). We Gotta Get Out of This Place: Popular Conservatism and Postmodern Culture. New York: Routledge.

Heathcote, D., & Bolton, G. (1995). Dorothy Heathcote’s Mantle of the Expert Approach to Education. Heinemann.

Hentschel, U. (2008). The So-Called Real. Playing With Reality in Theatre And Theatre Pedagogy. Speech given in Warschaw on October 4th, 2008. Retrieved from www.udkberlin.de/sites/theaterpaedagogik/content/e348/e111003/e111004/infoboxConten t111008/Theso-CalledReal_ger.pdf.

Hornbrook, D. (1998). Drama and education. In D. Hornbrook (Ed.), On the subject of drama. New York, NY: Routledge.

Hotel pro Forma (2015). Retrieved from www.hotelproforma.dk/projects/cosmos.

Jepperson, R., & Meyer, J. W. (2011). Multiple Levels of Analysis and the Limitations of Methodological Individualisms. In Sociological Theory 29:1. Washington: American Sociological Association. DOI:

Lehmann, H. T. (2006). Postdramatic Theatre. Oxon: Routledge. DOI:

Slade, P. (1973). Childdrama. London: University of London Press.

Szatkowski, J. (1985). Når kunst kan bruges – Om dramapædagogik og æstetik. In J. Szatkowski, & Chr. B. M. Jensen, (Eds.), Dramapædagogik i et nordisk perspektiv. Artikelsamling 2. Gråsten: Teaterforlaget Drama.

Ward, W. (1930). Creative Dramatics. New York, NY: D. Appleton & Co.

Way, B. (1967). Development through drama. London: Longmans.

Zich, O., & Sus, O. (1931). Estetika dramatického umění: teoretická dramaturgie (Vol. 14). Jal- reprint.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.