A Meta-Theoretical Approach into the Determinants of Internal Psychological Resources for Entrepreneurs

Abstract

This study, which was conducted in the context of a Small Island Developing state economy, adopts exploratory, meta-theoretical, and inter-disciplinary stances to examine determinants of internal psychological resources for entrepreneurs. It contributes to existing literature and methodology through its innovative interdisciplinary theoretical framework and the use of Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) in the field of entrepreneurship. Questionnaires were randomly distributed among 711 entrepreneurs, of which 539 were deemed useful for analytical purposes. EFA was used to identify factors that determine fundamental internal psychological resources for entrepreneurs. The Kaiser-Meyer Olkin coefficient of 0.85 justified the sample size for the use of EFA. The highly significant Barlett’s test (p<0.0001) showed the presence of adequately correlated items to form clusters. A coefficient of 0.00033 on the inverse of correlation matrix ruled out the possibility of multicollinearity issues among the six key EFA constructs of internal psychological resources for entrepreneurs. Inner Strength which originates from the field of medicine is surprisingly revealed as the leading internal psychological resource valued by entrepreneurs, followed by Entrepreneurial Aspirations, Entrepreneurial Alertness, Entrepreneurial Orientation, Self-leadership, and Risk Orientation. Two other concepts (Psychological capital and Sense of Coherence) which were initially included in the theoretical framework were eliminated during the EFA because the Scree plot did not support their retention and contributed to multicollinearity issues. This study has several practical and policy implications which will enable governments and entrepreneurs to contribute more effectively and more accurately to the entrepreneurial process.

Keywords: Exploratory Factory Analysis, Inner Strength, Entrepreneurial Aspirations, Entrepreneurial Alertness, Self-leadership

Introduction

This study is an exploratory and meta-theoretical endeavour in nature, incorporating concepts from the field of positive psychology such as Inner Strength, Self-Leadership, and Epistemic Motivation constructs and postulates these as potential determinants of internal psychological resources. Psychological resources of an individual are related to the performance of individual positive organisational behaviour and organisational scholarship. Although psychological resources have been termed as psychological capital (Han et al., 2012), this paper treats both concepts as distinct following the studies conducted by Luthans et al. (2007). There is a need to study the factors that affect psychological resources. Positive dimensions of psychological resources may be associated with perceived employee empowerment, low-stress levels, alternative job search behaviours (Han et al., 2012) reduced levels of voluntary and involuntary absenteeism (Costello & Osborne, 2005) reduced labour turnover intention, reduced deviant behaviour and cynicism, higher levels of positive emotions, increased organisational citizenship and engagement (Costello & Osborne, 2005) increased job satisfaction, greater organisational commitment, trust, and improved job performance (Costello & Osborne, 2005).

This study uses exploratory factor analysis (EFA) to identify the factors affecting inner psychological resources. The use of EFA is justified here because a complex model which reports high levels of variation has been assessed to be of low theoretical value (Costello & Osborne, 2005). Factor analysis is a multivariate method that aims to achieve parsimony in measured variables (Costello & Osborne, 2005; Preacher et al., 2013; Rummel, 1967). Parsimony is achieved through the statistical determination of commonalities within and across the measured variables. These commonalities relate to the nature of the factors and are detected in terms of patterns within the observed correlations (Fabrigar et al., 1999). A high degree of commonalities across the different variables may possibly hint towards correlation which may explain the determinants of psychological resources. The principle of parsimony guides towards having the optimal number of predictors that can explain psychological resources.

There is another school of thought about the external determinants of entrepreneurial behaviour (Frederick et al., 2019). However, these are outside the scope of the current research. The focus here is to examine the commonalities among the internal psychological resources for entrepreneurs. Thus, this paper starts with a review of the relevant academic literature, theories, and determinants of internal psychological resources, followed by an extensive justification of the methodology used. Subsequent sections critically examine all findings and present theoretical, methodological, practical, and policy implications. Suggestions for further research in the field of entrepreneurship are also provided.

Problem Statement

The rate of entrepreneurial failure is known to be high in most economies (Lafuente et al., 2019). Hence, most governments provide support for Small and Medium Enterprises; but; these initiatives mostly focus on external capital resources (Buffart et al., 2020). This is inadequate as entrepreneurs require an enhanced level of particular commitment and resilience to mitigate the risk of failure (Luthar et al., 2000). Additionally, entrepreneurs have special characteristics which require not only economic but also psychological support. Psychological resources are vital for entrepreneurial success. In short, the economic perspective alone does not provide a complete and comprehensive view on entrepreneurial success. This study responds to this problem by aspiring to understand the internal psychological resources of entrepreneurs from the humanistic psychological perspective.

Research Questions

This study outstrips what is already known within the field of entrepreneurship and basically answers these questions:

- Can an interdisciplinary stance be adopted to explain the key determinants of internal psychological resources for entrepreneurs?

- Can internal psychological resources be categorized into latent constructs and examined accordingly?

Purpose of Study

The selection of these theories was guided by the domain of positive psychology. The literature review of different theories revealed potential conceptual intersection. These theories were previously studied in isolation and some researchers had recommended their use in the field of business and management (Dingley & Roux, 2014). So, this study attempts to coalesce them by first sorting out concepts from theories that are relevant in the field of entrepreneurship and examining them accordingly. The motivation to pursue this investigation was to:

- assess the psychological resources across disciplines that share commonalities in the entrepreneurial field.

- examine the factors which determine the internal psychological resources in the context of entrepreneurs in Mauritius.

- critically examine the impacts of the determinants on internal psychological resources.

- inform policymaking on developing internal psychological resources for entrepreneurs in Mauritius and other countries with similar economic and cultural characteristics through recommendations and suggestions for future research.

Literature Review

This study takes a meta-theoretical perspective. A meta-theory shapes an ontological association of constructs and interactions relevant over a number of areas of research (Milton & Kazmierczak, 2006). This research covers concepts from theories such as Psychological Capital Theory, Self Determination Theory, Entrepreneurial Orientation Theory, Alertness Theory, Resource-Based Theory of the Firm, Theory of Lay Epistemics, Passion Theory, Salutogenic Theory, Grit Theory, Cognitive Consistency Theory and Goal-Setting Theory of Motivation. The chosen theories or part of these were deemed to be most appropriate in explaining the activation of internal psychological resources to form a psychological perspective. A clear illustration is provided in Table 1 where reference is made to few leading studies in the field.

The concept of ‘Inner Strength’ within the Salutogenesis Theory is grounded in psychology, sociology and the medical field. This theory relates to resistance resources that sustain individuals during difficult periods and motivates them to strive. It postulates that individuals have resources to be able to face negative life experiences. Inner strength focuses on the strength, capacities, and internal resources of individuals instead of the negative impacts of frailty (Smith et al., 2019). The concept of Inner Strength has been stated to hold promises in other fields of knowledge as the elements of Inner Strength comprise characteristics such as connectedness, firmness, flexibility, creativity, and hardiness which are applicable to the field of entrepreneurship (Dingley et al., 2000). Inner strength enables an individual to be firm and steady to face adversities and difficulties; transcend spiritual dimensions; and be able to determine one’s life trajectory, shoulder responsibility, and be able overcome adversities (Antonovsky, 1979; Lundman et al., 2010). Obviously, a successful entrepreneur needs these qualities, which justifies the need to connect inner strength to the field of entrepreneurship.

Another dimension of the Salutogenetic Theory related to entrepreneurship is ‘Sense of Coherence’. Antonovsky (1979) defined ‘Sense of Coherence’ as the extent to which an individual is confident in the predictability of his/her external and internal environments, availability of resources and the possibility of meeting demands, challenges, investments and engagement which means that the probability of things working out is high. This definition initially consisted of comprehensibility and manageability but later, a new dimension of ‘meaningfulness’ was added to this definition (Antonovsky, 1987). Comprehensibility has been described as the cognitive dimension; referring to the degree of rationality, order, coherence, and logic behind external and internal events. Meaningfulness refers to the motivational aspects of an individual’s life and relates to emotionality attached to events. Manageability is the behavioural aspect of an individual (Antonovsky, 1987)

The Cognitive Consistency Theory relates to the state of inconsistency that the mental systems struggle to avoid by developing various mechanisms to move away from a dissonant to a harmonious state. The Lay Epistemic Theory highlights the need for cognitive closure which is goal-oriented. Epistemic motivation involves the eagerness to participate in deep thinking (Scholten et al., 2007) and is autonomously constructed to make educated assumptions about the world (de Dreu et al., 2008). Epistemic motivation originally consisted of the need for cognition and the need for closure (Atak et al., 2017). The need for cognition deals with how individuals differ in terms of cognitive motivation, information processing (Dickhäuser et al., 2009), their ability to remember complex information, and make precise judgments after careful deliberation of available information tasks (Cacioppo et al., 1984). On the other hand, the need for closure may be defined as the refusal to overanalyse situations or business prospects in order to avoid confusion resulting in faster decision making (Kruglanski, 2004) and acting on predictable situations. However, the entrepreneur has to be sufficiently motivated and tolerant of risks before he/she can initiate the entrepreneurial process. Here, ambiguity which refers to the uncertainty or discomfort associated with a specific context, threat, or stimulus, comes into play.

Self-leadership relates to internally-driven, self-regulated behaviour (Manz, 1986; Brockner & Higgins, 2001). Over the last 30 years, studies on entrepreneurship have increasingly focussed on internal regulation (Boekaerts et al., 2000; Brockner & Higgins, 2001; Kanfer et al., 2008) thus, creating a prerequisite for a critical review of self-leadership in entrepreneurial studies. These studies also highlight the importance of the leader given that his/her actions eventually control external forces (Manz, 1986). Although the concept of self-leadership was primarily developed based on the idea that individual workers lead themselves, this concept was later extended to accommodate collective groups of workers (Campion et al., 1993; Cummings, 1978; Hackman, 1987) who were considered as being able to control their performance internally. Self-leadership, therefore, occurs at all organizational levels and may be analysed both at the individual and collective group levels.

Psychological capital is regarded as an advantage to the individual whereby his/her inner resources are deemed to be strengthened. It is a positive psychological state comprising four positive psychological resources which are optimism, self-efficacy, resilience, and hope. Individuals who display high self-efficacy demonstrate greater confidence that they can monitor the end-results of their actions, in tackling challenges (Bandura, 1982; 1989). Highly optimistic individuals develop positive expectations and anticipations that drive them (Seligman, 2006) enabling such individuals to confront difficult challenges. Individuals that have a high level of hope also demonstrate specific goal-directedness and the ability to adopt alternatives to achieve their objectives (Luthans et al., 2006).

Entrepreneurial Orientation (EO) has been established as influential concept in the literature (Martin & Javalgi, 2016). EO has been described at the firm level as the policies and procedures that support the entrepreneurial stance in response to emerging new business opportunities (Ngoma et al., 2017; Wales, 2016). EO at the firm level relate to the firm-level procedures, decision-making practices, and the strategic orientation which relates to risk-taking, innovativeness, proactiveness, competitiveness, and autonomy (Dess & Lumpkin, 2005; Gao et al., 2018; Kantur, 2016). Covin et al. (2020) posited that business units neglect the fact that as an orientation, EO may manifest at other levels of analysis. The significance of EO from the individual entrepreneurial orientation has been reported (Fatima & Bilal, 2019; Kraus et al., 2019; Martins & Perez, 2020; Santos et al., 2020) which applies to both individuals and organisations and is important for new or existing enterprises (Bolton & Lane, 2012). Accordingly, EO comprises innovativeness, proactiveness, and risk-taking propensity.

Entrepreneurs operate in competitive environments which affects their strategic stance and performance (Gatignon & Robertson, 1993). It may be argued that entrepreneurs address the environmental challenges through schemas. A schema is developed based on the signals emitted by the business environments which the entrepreneur interprets to determine the fate of his/her enterprise. Different individuals build different schemata for emerging opportunities. These lead to what is called a ‘hunch’ or what may be described as a chronic alertness schema or the heuristic driving awareness (Gaglio & Katz, 2001). The alertness theory may be used to explain this hunch and according to Kirzner (2009) there is a need to stress on spontaneity once opportunities or signals of change are perceived. However, identifying these is not enough; these must be interpreted correctly in order to achieve the desired end (Gaglio & Katz, 2001). There is also a need to respond to various economic, regulatory, technological, and social changes; thereby, referred to as entrepreneurial alertness.

The Goal-Setting Theory of Motivation is a popular and well-developed theory that emphasises the key relationship between goals and performance (Tosi et al., 1991). The level and type of motivation are posited to influence the individual’s orientation to proceed on the entrepreneurial process (Locke, 2000). Here, the entrepreneur’s aspiration is taken into consideration. Aspiration refers to the goal content that an individual activates to respond and satisfy his needs (Kasser & Ryan, 1993). The entrepreneurs’ aspirations were studied through specific elements that relate to perceived performance (Deci & Ryan, 2000). Entrepreneurial aspirations have been conceptualised as the drive behind entrepreneurial behaviour and are supported by the theory of planned behaviour (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1977), entrepreneurial mindset and intent (Thompson, 2009). Penrose (1959) argued that the entrepreneurs perceive and imagine the outcomes of their venture which then mould their subjective business performance.

Research Methods

Research design

The meta-theoretical base of the proposed conceptual model was designed based on the conceptual relationship of the concepts to internal psychological resources. A quantitative approach was used whereby a questionnaire was designed based on existing instruments from literature. The questionnaire contained Likert-type items, ranging from 3 to 7 options. These were distributed among entrepreneurs irrespective of the size of their business, sector, gender, and age. However potential respondents were identified based on the age of the business. This was used to filter out the established businesses and start-ups. The limit was set to 5 years of operation to ensure that the venture was stable and could be used as an indicator of adequate entrepreneurial experience.

Initially, a pilot study was conducted among 25 respondents. The objectives of conducting a pilot align with the fact that the instruments selected were from literature in different contexts. The pilot was undertaken to ensure the contextual validity of the instruments. Language and ease of comprehension were tested. The final questionnaire was modified according to the feedback obtained during the pilot study. Data were collected randomly across the island of Mauritius. Various options for gathering data were used. Some questionnaires, for instance, were administered online through the google survey. Following Roopnah and Sanmukhiya (2018) other questionnaires were administered on a face-to-face basis, after which the researcher had informal chats with the respondents to probe further on the topic under study. A few questionnaires were dispatched to the sample entrepreneurs’ workplace, and these were collected at a later stage. In line with the study conducted by Sanmukhiya (2019) data was gathered from only those who volunteered to participate in the survey with the condition that they could terminate their participation in the survey at any time.

The ease and time taken to complete the initial questionnaires were monitored to ensure that the respondents had read the questions before answering them. Respondents took about 40 minutes to fill in the questionnaires on average. Questionnaires containing missing information, filled within a maximum of 25 minutes or too many ‘neutral’ answers were eliminated from data analysis. These indicated that some respondents filled in the questionnaires just for sake of filling them without properly addressing each item. Other respondents did not reveal their opinions on the items being measured either because they chose not to do so or because they could not make up their minds or because they could not understand the question. Such data were deemed unfit to be used for policymaking. Around 750 questionnaires were distributed but only 539 questionnaires were deemed fit for analysis. The final questionnaire carried 80 items but during the analysis, only 53 items were retained because of a greater percentage of blank and neutral answers on the remaining items.

Characteristics of participants

The sampled entrepreneurs came from all walks of life, all types of ownership, and different industries to provide a national representation of Mauritian entrepreneurs. The majority of businesses included in the sample were founded between five to ten years and categorized as small enterprises where most of the entrepreneurs were women, Hindus, had studied up to secondary level and aged between 30 to 40 years. These characteristics of the respondents align with the demographic profile of the Mauritian population.

Data Analysis Procedure

Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was used for data analysis. EFA is a method that reduces a large number of items on the questionnaire to a reasonable set of items grouped to explain a particular phenomenon. This study thus centres around factor reduction aimed to detect fundamental concepts that predict internal psychological resources of entrepreneurs. EFA also generates a hierarchy of factors based on the proportion of variances that they explain or the extent to which they influence internal psychological resources. The Statistical Software for Social Sciences (SPSS) was used for all analyses.

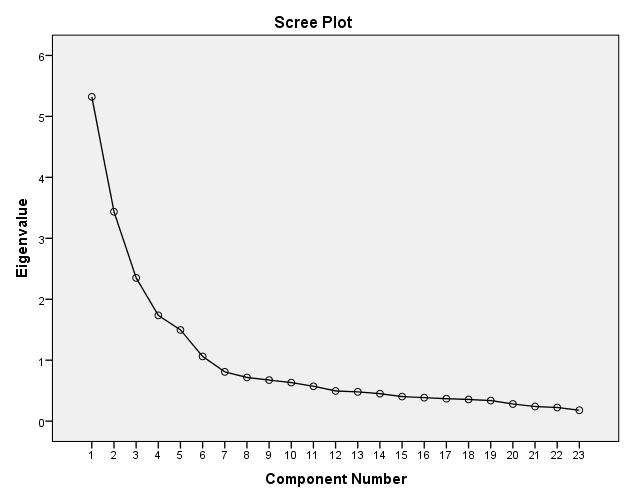

The scree plot is a visual representation of the factor distribution. Any sample size exceeding 200 cases dictates the need to refer to the scree plot as an alternative (Cattell, 1966; Ledesma et al., 2015). This study’s sample size being 539 created the need for the scree plot to be utilised to extract the relevant factors. Field (2009) stated that the eigenvalue and the scree plot can be used in conjunction to assess the relevance of factors. In this study, both criteria were satisfied. The scree plot was used and all eigenvalues exceeding 1 were retained. A close examination of the scree plot in Figure 1 reveals that it tails off after 7 components so only the first six components were retained. Theoretically, retaining the six components also made sense as it facilitated informing policy despite the fact that all the items under the concepts of psychological capital and sense of coherence were eliminated. The EFA was repeated until the pattern matrix did not contain any missing loading value. Following Field (2009) and Sanmukhiya (2018), anything under the value of 0.4 were not considered during the extraction procedure.

Eventually, the six components were labelled as follows: Inner Strength, Entrepreneurial Aspirations, Entrepreneurial Alertness, Individual Entrepreneurial Orientation, Self-Leadership, and Risk Tolerance. These six components together explained around 67% of the total variances in internal psychological resources. Each component has a Cronbach Alpha exceeding the value of 0.7 (except for risk orientation) and inter-item correlation coefficients above 0.3. The Cronbach Alpha for the construct ‘risk orientation’ is above 0.6 which is acceptable for exploratory research. These support the internal consistency of each item and the reliability within each component. Table 2 provides the summary statistics of the analysis. The selection of the oblique rotation is justified on the psychological ground which states that human reactions are inter-linked as situations are interrelated. Also, some of the coefficients on the component correlation matrix exceed 0.32. This rationale aligns with Sanmukhiya (2018)’s study where the Promax rotation was utilised because it is more appropriate to the sample size of the data.

Findings and Discussion

The concept ‘Inner Strength’ emerged as the most influential factor on internal psychological resources. Inner Strength is a concept that is related to positive psychology and the medical field of Salutogenic orientation to health. According to the EFA conducted for this research, Inner Strength is the most influential factor within the ‘internal psychological resources’ paradigm for entrepreneurs. Inner Strength emerged as the leading construct; thus, establishing its importance and relevance in the literature for entrepreneurship. Originally related to positive health science, the sub-dimensions of Inner strength which are connectedness, firmness, flexibility, creativity, and hardiness can be attributed to entrepreneurial traits (see Table 3). Entrepreneurs, by their very nature, must possess the inner strength to be open to life and its possibilities; to be excited to learn and try new things; to see challenges as opportunities and are bold to face challenges. Table 3 shows the components of Inner Strength.

The second construct, ‘Entrepreneurial Aspirations’, emerges from the Goal Setting Theory. The items initially on the scale are narrowed down to five items during the EFA as illustrated in Table 4. Aspirations are multifaceted as individuals aspire to satisfy their physiological and psychological needs (Kasser & Ryan, 1993). Entrepreneurial Aspirations encompass economic, social, psychological, and physiological domains. Aspirations relate to individuals’ goals although an ‘aspiration’ itself differs from ‘goal’ as it is more elusive than the latter. Goals are more precise and are milestones in the achievement of generic aspirations. Goals being specific can be attained, whilst aspirations being more abstract may not fully accomplished. In this paper, aspirations reflect the importance of growth in sales, profit, and finance as well as the ability to increase sales faster than rivals and the ability of the entrepreneur to reduce his/her debts.

The EFA results suggest that ‘Entrepreneurial Alertness’ is the third most influential internal psychological resource that an entrepreneur should possess. Entrepreneurial alertness (see Table 5) is considered to be a key element highlighted in this study. Here ‘alertness’ emphasises the role of strategic management by properly acknowledging and recognising opportunities, allocating the necessary internal and external organizational resources, and the ability to respond to changing environments.

In the current study, the term ‘entrepreneurial alertness’ is used to describe the business mindset of entrepreneurs. They should be able to withstand stress, predict customers’ tastes and meet customers’ demands by adapting their marketing activities and simultaneously responding to the rapidly changing technological and hostile business environment. This may be termed as Perceived Industry Dynamism as it can be argued that successful entrepreneurs are those individuals who are dynamic and whose resilience enables them to perceive and adapt to changes in environments (Luthans et al., 2006). Table 5 below shows the components related to Entrepreneurial Alertness

This study aligns with Zhao et al (2020)’s argument that Entrepreneurial Alertness facilitates business innovation. Hence, Entrepreneurial Alertness precedes the concept of ‘Entrepreneurial Orientation’. Entrepreneurial Orientation (see Table 6) emerged as the fourth construct comprising the internal psychological resources of entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurial Orientation can be applied at the firm or individual level (Martins & Perez, 2020). In small ventures, the firm has been studied to be an extension of the entrepreneur (Markman & Baron, 2003). In line with the findings of (Vallerand & Verner-Filion, 2013), this study acknowledges the existence of harmonious and obsessive passion although it does not seek to distinguish between them. Here Entrepreneurial Orientation may be examined as the passion imbued in an entrepreneur’s actions, the ability to overcome setbacks, the impatience to return to one’s business when one is called away to attend to something else and the passion of engaging in the process to gather the required human, financial and social resources to generate more business. This concurs with Rauch and Frese (2007) who noted a positive relationship between passion and entrepreneurial behaviour.

Self-leadership (see Table 7) was reported to be the fifth important characteristic that an entrepreneur requires under his/her umbrella of internal psychological resources. When faced with problems, leaders sometimes talk to themselves and mentally evaluate the accuracy of their assumptions and beliefs. This was supported by D'Intino et al. (2007) who content that self-leadership drives performance. Self-leadership has been studied in the field of entrepreneurship. The process of self-influence to set self-direction and motivation to achieve goals is related to the entrepreneurial process. The entrepreneur’s behaviour is determined by his or her cognitive and emotive aspects (Ebbers, 2014; Grégoire et al., 2011). This study reveals that self-leadership is an important factor in the nature of the entrepreneurs studied which concurs with D’Intino et al. (2007). However, in terms of importance, it has been rated lower on the scale of importance compared to other dimensions which took precedence over self-leadership.

The final component of entrepreneurial psychological resources is ‘Risk Orientation’ (see table 8). Risk orientation for the purpose of this study however, refers to prudence, which is also an important psychological resource whereby entrepreneurs exhibit a greater willingness than employees to take higher but calculated risks and to avoid extreme risks. Besides, it is argued that entrepreneurs are individuals who are competent in managing their risk exposure (Stewart & Roth, 2001). The results in this study suggest that entrepreneurs displayed discomfort when associated with life events that they could not explain or control. They were also averse to unpredictable situations and outcomes. This final component of the EFA in this paper aligns with the existing literature. Kreiser et al. (2010) reported that individuals indicating a great need for achievement were ambitious and more willing to engage in taking calculated business-related risks. It is reported that entrepreneurs modulate their risk as per their assessment of the success potential of a venture (Macko & Tyszka, 2009). Entrepreneurs relate their risk propensity to the potential performance and success they can derive from their efforts.

Conclusions and Implications

This study incorporates different theoretical domains for a comprehensive understanding of the internal drivers of psychological resources for entrepreneurs. The main finding of this meta-theoretical study is that inner strength is of utmost relevance to entrepreneurship while risk orientation was perceived to be of least value by entrepreneurs. Inner strength may have emerged as the dominant dimension supporting entrepreneurial behaviour as it focuses on the entrepreneur’s capacity to face and overcome challenges, which are part and parcel of the business environment. Associated with inner strength is entrepreneurial confidence which also emerged as another important dimension driving entrepreneurial behaviour. Confidence is the foundation for anyone involved in business as setting up and sustaining a business is grounded in taking calculated risks. Although it was perceived as the least important driver for entrepreneurial behaviour, taking calculated risks is closely associated with the dimension of risk orientation as a component of entrepreneurial psychological resources. In order to be a successful entrepreneur, one would need to be constantly alert for opportunities and threats which is related to the dimension of Entrepreneurial Alertness. Business is a dynamic phenomenon requiring entrepreneurs to maintain an awareness of their proximate environments in order to plan and execute their business strategies. Hence, Entrepreneurial Alertness is dependent on Entrepreneurial Orientation which is the ability to identify, pursue and successfully exploit emerging business opportunities. All these dimensions however, cannot be activated without personal passion and perseverance. As such, self -leadership is a highly-valued dimension as entrepreneurs need to align their cognitive, conative and behavioural capabilities to attain the requisite entrepreneurial goals. Entrepreneurs must, before anything else, practice self-leadership; they must be able to set and abide by personal goals and strategies to achieve those goals.

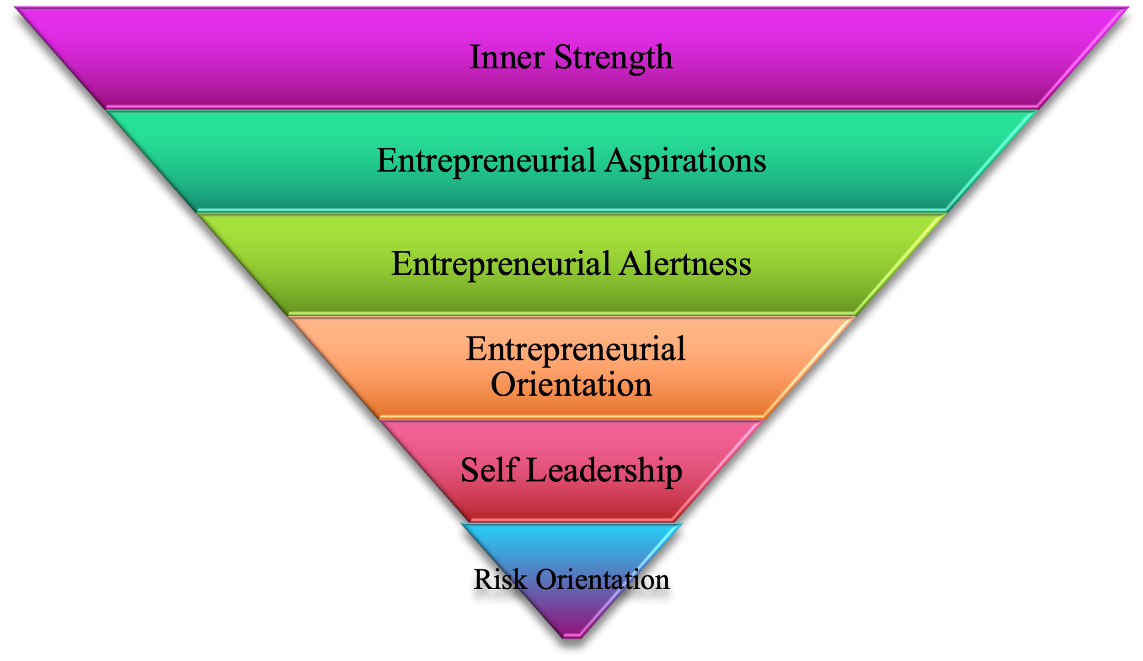

This paper contributes to existing literature by providing empirical evidence on entrepreneurship, more specifically on internal psychological resources for entrepreneurs. Important theoretical contributions include the addition of specific sub-concepts such as Inner Strength, Entrepreneurial Aspirations, Entrepreneurial Alertness, Entrepreneurial Orientation, Self-leadership, and Risk Orientation within the theoretical framework of internal entrepreneurial psychological resources. These sub-concepts are ranked in order of their importance according to the findings of this study (see Figure 2). This study also highlights the relevance of incorporation of multi-disciplinary concepts, for example, the Salutogenetic Theory from the medical field transformed into ‘Inner Strength’ as an internal psychological resource in the case of entrepreneurs.

An important methodological contribution has also been made to the field of entrepreneurship. The EFA was found to be an important tool to explain factors that determine internal psychological resources for entrepreneurs and the oblique rotation was used to ensure that the interdependence of determinants is not overlooked during the EFA procedure. This procedure has generated stable, reliable, and valid results. Thus, the use of EFA may be encouraged during research on entrepreneurship.

This study also has key practical implications for both potential and existing entrepreneurs. The novel, clear and concise framework provided in this paper eliminates ambiguity for entrepreneurs and researchers when reviewing the extensive literature and empirical evidence on entrepreneurship. The most influential factors in their order of importance that drive the internal psychological resources paradigm for entrepreneurs has been clearly delineated in this study.

This study reveals that, on a policy level, governments need to invest more in entrepreneurial development programmes focusing on internal psychological resources of the entrepreneur. This can be done through relevant training to enhance the psychological resources of the entrepreneurs. It has been reported that policies to support entrepreneurship are not effective (Hart, 2009). Thus, investing resources to enhance the internal psychological resources of entrepreneurs may have a better bearing on developing effective entrepreneurs as these resources have a direct bearing on the capabilities, such as inner strength, alertness, confidence and self-leadership, to achieve their aspirations. This study was done in the context of a Small Island Developing States (SIDS) economy. However, the proposed framework can be further studied in a different context to assess its predictive potency. The concept of inner strength can also be further examined in different contexts to assess cross-theoretical validity. All in all, this study’s findings and proposed framework has great potential value to researchers and policy makers who are dedicated to enhancing entrepreneurship.

Acknowledgements

The author(s) declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

Abelson, R. P., Aronson, E., McGuire, W. J., Newcomb, T. M., Rosenberg, M. J., & Tannenbaum, P. H. (1968). Theories of cognitive consistency: a sourcebook. Rand-McNally.

Ahunov, M., & Yusupov, N. (2017). Risk attitudes and entrepreneurial motivations: Evidence from transition economies. Economics Letters, 160, 7–11.

Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1977). Attitude-Behavior Relations: A Theoretical Analysis and Review of Empirical Research. Psychological Bulletin, 84(5), 888–918.

Al-Jubari, I., Mosbah, A., & Talib, Z. (2019). Do Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation Relate to Entrepreneurial Intention Differently? A Self-Determination Theory Perspective. Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal, 25(2)

Antonovsky, A. (1979). Health, stress and coping. Jossey-Bass.

Antonovsky, A. (1987). Unraveling the mystery of health: How people manage stress and stay well. Jossey-Bass.

Atak, H., Syed, M., & Çok, F. (2017). Examination of psychometric properties of the need for closure scale-short form among Turkish college students. Noropsikiyatri Arsivi, 54(2), 175–182.

Baluku, M. M., Kikooma, J. F., Bantu, E., & Otto, K. (2018). Psychological capital and entrepreneurial outcomes: the moderating role of social competences of owners of micro-enterprises in East Africa. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, 8(1).

Bandura, A. (1982). Self-Efficacy Mechanism in Human Agency. American Psychologist, 37(2), 122–147.

Bandura, A. (1989). Human Agency in Social Cognitive Theory: The Nature and Locus of Human Agency. Am Psychol, 44(9), 1175-84.

Barbosa, S. D., & Fayolle, A. (2007). Where is the Risk? Availability, Anchoring, and Framing Effects on Entrepreneurial Risk Taking. Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research, 27(6), 1-15. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228314758

Barney, J. (1991). Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99-120. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F014920639101700108

Boekaerts, M., Pintrich, P., & Zeidner, M. (2000). Self-Regulation: An Introductory Overview. In P. Boekaerts, P. Pntrich, & M. Zeidner (Eds.), Handbook of Self-Regulation (pp. 1-9). Elsevier Science and Technology.

Bolton, D. L., & Lane, M. D. (2012). Individual entrepreneurial orientation: Development of a measurement instrument. Education and Training, 54(2-3), 219-233.

Brockhaus, R. H. (1980). Risk Taking Propensity of Entrepreneurs. The Academy of Management Journal, 23(3), 509-520. https://about.jstor.org/terms

Brockner, J., & Higgins, E. T. (2001). Regulatory focus theory: Implications for the study of emotions at work. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 86(1), 35-66.

Browning, M. (2018). Self-Leadership: Why It Matters. In International Journal of Business and Social Science, 9(2). www.ijbssnet.com

Buffart, M., Croidieu, G., Kim, P. H., & Bowman, R. (2020). Even winners need to learn: How government entrepreneurship programs can support innovative ventures. Research Policy.

Cacioppo, J. T., Petty, R. E., & Kao, C. F. (1984). The Efficient Assessment of Need for Cognition. Journal of Personality Assessment, 48(3), 306–307.

Campion, M. A., Medsker, G. J., & Higgs, C. A. (1993). Relations between work group characteristics and effectiveness: implications for designing effective work groups. Personnel Psychology, 46(4), 823-850.

Carland, J. W., Hoy, F., Boulton, W. R., & Carland, J. A. C. (1984). Differentiating Entrepreneurs from Small Business Owners: A Conceptualization. Academy of Management Review, 9(2), 354-359.

Cattell, R. B. (1966). The scree test for the number of factors. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 1(2), 245–276.

Chintamanee, S. (2018). E-Government in Mauritius: A Principal Component Analysis. The European Proceedings of Social & Behavioural Sciences, 1019–1035.

Costello, A. B., & Osborne, J. W. (2005). Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: Four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Practical Assessment, Research and Evaluation, 10(7).

Covin, J. G., & Lumpkin, G. T. (2011). Entrepreneurial orientation theory and research: Reflections on a needed construct. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 35(5), 855-872.

Covin, J. G., Rigtering, J. P. C., Hughes, M., Kraus, S., Cheng, C. F., & Bouncken, R. B. (2020). Individual and team entrepreneurial orientation: Scale development and configurations for success. Journal of Business Research, 112, 1–12.

Cummings, T. G. (1978). Self-Regulating Work Groups: A Socio-Technical Synthesis. The Academy of Management Review, 3(3), 625–634.

de Dreu, C. K. W., Nijstad, B. A., & van Knippenberg, D. (2008). Motivated information processing in group judgment and decision making. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 12(1), 22-49.

de Jong, P., & Özcan, E. (2016). Tolerance of ambiguity in relationship to creativity and its implications for design practice. In Celebration & Contemplation: Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on Design and Emotion. 27-30 September 2016, Amsterdam.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2012). Self-determination theory. In P. A. van Lange, A. W. Kruglanski, & E. T. Higgin (Eds.), Handbook of theories of social psychology (pp. 416-436, Vol 1). Sage.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “What” and “Why” of Goal Pursuits: Human Needs and the Self-Determination of Behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268.

Dess, G. G., & Lumpkin, G. T. (2005). Research Edge: The Role of Entrepreneurial Orientation in Stimulating Effective Corporate Entrepreneurship. The Academy of Management Executive, 19(1), 147-156.

Dickhäuser, O., Reinhard, M. A., Diener, C., & Bertrams, A. (2009). How need for cognition affects the processing of achievement-related information. Learning and Individual Differences, 19(2), 283-287.

Dingley, C. E., Roux, G., & Bush, H. A. (2000). Inner strength: A concept analysis. Journal of Theory Construction & Testing, 4(2), 30-35.

Dingley, C., & Roux, G. (2014). The role of inner strength in quality of life and self-management in women survivors of cancer. Research in Nursing and Health, 37(1), 32–41.

D’Intino, R. S., Goldsby, M. G., Houghton, J. D., & Neck, C. P. (2007). Self-Leadership: A Process for Entrepreneurial Success. Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies, 13(4), 105-120. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/

Duckworth, A. L., Peterson, C., Matthews, M. D., & Kelly, D. R. (2007). Grit: Perseverance and Passion for Long-Term Goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(6), 1087-1101.

Ebbers, J. J. (2014). Networking Behavior and Contracting Relationships Among Entrepreneurs in Business Incubators. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 38(5), 1159-1181.

Fabrigar, L. R., Wegener, D. T., MacCallum, R. C., & Strahan, E. J. (1999). Evaluating the Use of Exploratory Factor Analysis in Psychological Research. Psychological Methods, 4, 272-299.

Fatima, T., & Bilal, A. R. (2019). Achieving SME performance through individual entrepreneurial orientation: An active social networking perspective. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 12(3), 399-411.

Field, A. (2009). Discovering Statistics Using SPSS (and sex and drugs and rock’n’ all) (3rd ed.). Sage Publishing.

Flensborg-Madsen, T., Ventegodt, S., & Merrick, J. (2005). Sense of Coherence and Physical Health. A Review of Previous Findings. The Scientific World JOURNAL, 5, 665-673.

Frederick, H., O’Connor, A., & Kuratko, D. F. (2019). Entrepreneurship: theory/process/practice (5th Asia-Pacific). Centage.

Gaglio, C. M., & Katz, J. A. (2001). The Psychological Basis of Opportunity Identification: Entrepreneurial Alertness. Small Business Economics, 16(2), 95–111.

Gao, Y., Ge, B., Lang, X., & Xu, X. (2018). Impacts of proactive orientation and entrepreneurial strategy on entrepreneurial performance: An empirical research. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 135, 178–187.

Gartner, W. B., & Shane, S. A. (1995). MEASURING ENTREPRENEURSHIP OVER TIME*. In Journal of Business Venturing, 10(4), 283-301.

Gatignon, H., & Robertson, T. S. (1993). The Impact of Risk and Competition on Choice of Innovations. Marketing Letters, 4(3), 191-204. https://about.jstor.org/terms

Grégoire, D. A., Corbett, A. C., & Mcmullen, J. S. (2011). The Cognitive Perspective in Entrepreneurship: An Agenda for Future Research. In Journal of Management, 48(6), 1443-1477).

Hackman, J. R. (1987). The design of work teams. In J. L. Lorsch (Ed.), Handbook of organizational behaviour (pp. 315–342). Prentice Hall.

Han, Y., Brooks, I., Kakabadse, N. K., Peng, Z., & Zhu, Y. (2012). A grounded investigation of Chinese employees’ psychological capital. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 27(7), 669–695.

Hart, D. (2009). The emergence of entrepreneurship policy. Cambridge University Press.

Hunt, S. D., & Morgan, R. M. (1995). The Comparative Advantage Theory of Competition. In Source: Journal of Marketing, 59(2), 1-15.

Kanfer, R., Chen, G., & Pritchard, R. D. (2008). Work motivation: Past, present, and future. Routledge.

Kantur, D. (2016). Strategic entrepreneurship: mediating the entrepreneurial orientation-performance link. Management Decision, 54(1), 24-43.

Kasser, T., & Ryan, R. M. (1993). A Dark Side of the American Dream: Correlates of Financial Success as a Central Life Aspiration. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65(2), 410-422.

Kirzner, I. M. (2009). The Alert and Creative Entrepreneur: A Clarification. Small Business Economics, 32(2), 145-152.

Koestner, R. (2008). Reaching one’s personal goals: A motivational perspective focused on autonomy. In Canadian Psychology, 49(1), 60-67.

Kraus, S., Breier, M., Jones, P., & Hughes, M. (2019). Individual entrepreneurial orientation and intrapreneurship in the public sector. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 15(4), 1247-1268.

Kreiser, P. M., Marino, L. D., Dickson, P., & Weaver, K. M. (2010). Cultural influences on entrepreneurial orientation: The impact of national culture on risk taking and proactiveness in SMEs. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 34(5), 959-983.

Kruglanski, A.W. (1989). The Psychology of Being “Right”: The Problem of Accuracy in Social Perception and Cognition. Psychological Bulletin, 106(3), 395-409. https://

Kruglanski, A.W., Orehek, E., Dechesne, M., & Pierro, A. (2010). Lay Epistemic Theory: The Motivational, Cognitive, and Social Aspects of Knowledge Formation. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 4(10), 939-950.

Kruglanski, A.W. (2004). The Psychology of closed-mindedness. Psychology Press.

Lafuente, E., Vaillant, Y., Vendrell-Herrero, F., & Gomes, E. (2019). Bouncing Back from Failure: Entrepreneurial Resilience and the Internationalisation of Subsequent Ventures Created by Serial Entrepreneurs. Applied Psychology, 68(4), 658–694.

Ledesma, R. D., Valero-Mora, P., & Macbeth, G. (2015). The Scree Test and the Number of Factors: a Dynamic Graphics Approach. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 18, E11.

Lee, J. H., & Venkataraman, S. (2006). Aspirations, market offerings, and the pursuit of entrepreneurial opportunities. Journal of Business Venturing, 21(1), 107–123.

Lian, J. W., & Yen, D. C. (2017). Understanding the relationships between online entrepreneurs’ personal innovativeness, risk taking, and satisfaction: Comparison of pure-play and click-and-mortar. Journal of Organizational Computing and Electronic Commerce, 27(2), 135–151.

Locke, E. A. (2000). Motivation, Cognition, and Action: An Analysis of Studies of Task Goals and Knowledge. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 49(3), 408-429. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/

Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (2002). Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation: A 35-year odyssey. American Psychologist, 57(9), 705–717.

Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (2013). New developments in goal setting and task performance. Routledge.

Lundman, B., Aléx, L., Jonsén, E., Norberg, A., Nygren, B., Santamäki Fischer, R., & Strandberg, G. (2010). Inner strength-A theoretical analysis of salutogenic concepts. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 47(2), 251–260.

Luthans, F., Avey, J. B., Avolio, B. J., & Peterson, S. J. (2010). The development and resulting performance impact of positive psychological capital. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 21(1), 41–67.

Luthans, F., Avolio, B. J., Avey, J. B., & Norman, S. M. (2007). Positive psychological capital: measurement and relationship with performance. Personnel Psychology; Autumn, 60(3), 541-572.

Luthans, F., Vogelgesang, G. R., & Lester, P. B. (2006). Developing the Psychological Capital of Resiliency Part of the Business Administration, Management, and Operations Commons, Management Sciences and Quantitative Methods Commons, and the Strategic Management Policy Commons. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/managementfacpub

Luthar, S. S., Cicchetti, D., & Becker, B. (2000). The construct of resilience: a critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child development, 71(3), 543-562.

Luthans, F., & Youssef-Morgan, C. M. (2017). Psychological capital: An evidence-based positive approach. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 4, 339-366.

MacKo, A., & Tyszka, T. (2009). Entrepreneurship and risk taking. In Applied Psychology, 58(3), 469–487.

Manz, C. C. (1986). Self-Leadership: Toward an Expanded Theory of Self-Influence Processes in Organizations. The Academy of Management Review, 11(3), 585-600.

Markman, G. D., & Baron, R. A. (2003). Person-entrepreneurship fit: Why some people are more successful as entrepreneurs than others. Human Resource Management Review, 13(2), 281–301.

Martin, S. L., & Javalgi, R. R. G. (2016). Entrepreneurial orientation, marketing capabilities and performance: The Moderating role of Competitive Intensity on Latin American International New Ventures. Journal of Business Research, 69(6), 2040–2051.

Martins, I., & Perez, J. P. (2020). Testing mediating effects of individual entrepreneurial orientation on the relation between close environmental factors and entrepreneurial intention. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour and Research, 26(4), 771–791.

Miettola, J., & Viljanen, A. M. (2014). A salutogenic approach to prevention of metabolic syndrome: A mixed methods population study. Scandinavian Journal of Primary Health Care, 32(4), 217–225.

Milton, S. K., & Kazmierczak, E. (2006). Ontology as Meta-Theory: A Perspective. Scandinavian Journal of Information Systems, 18(1), 85–94.

Mitonga-Monga, J., & Mayer, C. H. (2020). Sense of coherence, burnout, and work engagement: The moderating effect of coping in the Democratic Republic of Congo. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(11), 1–16.

Ngoma, M., Ernest, A., Nangoli, S., & Christopher, K. (2017). Internationalisation of SMEs: does entrepreneurial orientation matter? World Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Sustainable Development, 13(2), 96–113.

Norton, W. I., & Moore, W. T. (2002). Entrepreneurial risk: Have we been asking the wrong question? In Small Business Economics, 18(4), 281–287.

Penrose, E. T. (1959). The Theory of the Growth of the Firm. Blackwell.

Preacher, K. J., Zhang, G., Kim, C., & Mels, G. (2013). Choosing the Optimal Number of Factors in Exploratory Factor Analysis: A Model Selection Perspective. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 48(1), 28–56.

Rauch, A., & Frese, M. (2007). Let’s put the person back into entrepreneurship research: A meta-analysis on the relationship between business owners’ personality traits, business creation, and success. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 16(4), 353–385.

Roopnah, M., & Sanmukhiya, C. (2018). Causes of voluntary labour turnover: a case study of a five star hotel in Mauritius. Proceedings of SOCIOINT 2018- 5th International Conference on Education, Social Sciences and Humanities, 586–600. 2 – 4 July, 2018, Dubai

Ruiz-Frutos, C., Ortega-Moreno, M., Allande-Cussó, R., Ayuso-Murillo, D., Domínguez-Salas, S., & Gómez-Salgado, J. (2021). Sense of coherence, engagement, and work environment as precursors of psychological distress among non-health workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain. Safety Science, 133.

Rummel, R. J. (1967). Understanding factor Analysis. The Journal of Conflict Resolution, 11(4), 444-480. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F002200276701100405

Sanmukhiya, C. (2019). E-governance dimensions in the republic of Mauritius. Humanities and Social Sciences Reviews, 7(5), 264–279.

Santos, G., Marques, C. S., & Ferreira, J. J. M. (2020). Passion and perseverance as two new dimensions of an Individual Entrepreneurial Orientation scale. Journal of Business Research, 112, 190-199.

Scholten, L., van Knippenberg, D., Nijstad, B. A., & de Dreu, C. K. W. (2007). Motivated information processing and group decision-making: Effects of process accountability on information processing and decision quality. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 43(4), 539-552.

Seligman, M. (2006). Learned Optimism. Vintage Books.

Smith, C. S., Dingley, C., & Roux, G. (2019). Inner Strength-State of the Science. The Canadian journal of nursing research, 51(1), 38-48.

Stewart, W. H. J., & Roth, P. L. (2001). Risk Propensity Differences Between Entrepreneurs and Managers: A Meta-Analytic Review. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(1), 145-153.

Thompson, E. R. (2009). Individual Entrepreneurial Intent: Construct Clarification and Development of an Internationally Reliable Metric. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(3), 669-694.

Tosi, H. L., Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (1991). A Theory of Goal Setting and Task Performance. The Academy of Management Review, 16(2), 480.

Vallerand, R. J., & Verner-Filion, J. (2013). Making People’s Life Most Worth Living: On the Importance of Passion for Positive Psychology. Terapia Psicologica, 31(1), 35–48.

Wales, W. J. (2016). Entrepreneurial orientation: A review and synthesis of promising research directions. International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship, 34(1), 3–15.

Zhao, W., Yang, T., Hughes, K. D., & Li, Y. (2020). Entrepreneurial alertness and business model innovation: the role of entrepreneurial learning and risk perception. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal., 17, 839–864.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.