Abstract

Youth employment programmes are used as a means of developing employability skills through a wage subsidy strategy. This study examines the effectiveness of the Youth Employment Programme (YEP) in Mauritius in terms of the trainee’s satisfaction of YEP, his/her belief that YEP would help him/her to get a job and the odds of actually being employed once the programme is over. The Human Capital Theory is used to describe the transformation process through which YEP increases youth employability. Data was randomly collected among 214 individuals who were either currently or had previously been on the programme. All logistic models fitted the data well with correct classifications ranging from 70% to 92.5%. None of the demographic factors predicted the effectiveness of YEP. Trainees’ satisfaction was predicted by the sector of work placement, quality of programme, field of study and recommendations. Trainees’ beliefs were predicted by the number of interviews, duration of unemployment prior to the programme, whether internship matched their fields of study, nature of employment and quality of the programme. However, the nature of employment and salary were the only factors that predicted the odds of actually being employed. The YEP in Mauritius may require major restructuration to cater for trainees outside the field of social sciences. Although the YEP has failed to provide the adequate support and a satisfying experience, its contribution cannot be underestimated. An evaluation of the programme should be carried out at shorter intervals to detect major loopholes so that these may be resolved in time.

Keywords: Human capital theory, logistic regression, youth employment programmes, Hosmer and Lemeshow test

Introduction

Several studies have pinpointed the lack of employability skills (such as teamwork, communication skills and problem-solving skills), skill mismatch and work experience as the major causes of youth unemployment (Agwani 2014; Dobric 2018; Gokulsing, 2018; Pheko & Molefhe 2016). Also, hiring youngsters may be costly to employers. The Center for Human Services Research University in Albany (2017) reports that youth unemployment can lead to juvenile delinquency, substance abuse, poverty, low economic growth, higher government spending and low tax revenues. To overcome these problems, many countries have implemented youth employment programmes. It may be argued that employment programmes are guided by the Human Capital Theory. In line with this theory, employment programmes provide internships, on the job training and apprenticeships to young people to increase their knowledge and skills. Ultimately these programmes develop human resources in the economy (Almendarez 2011; Mincer 1962). Such programmes have positive impacts on youth employability (Smee et al., 2014).

The Youth Employment Programme (YEP) is the dominant training programme among unemployed young Mauritians. It was initiated by the Government of Mauritius in 2013 to enable young unemployed Mauritians (aged between 16 to 24 years) to initially obtain training or work placements for a year. The idea was to assist employers in finding manpower and, simultaneously, providing unemployed youth with a platform where they could develop the required labour skills that would eventually help them to obtain permanent employment either at their work placements or elsewhere after the one year had lapsed. The YEP offers work placement in a wide range of fields such as agriculture, ICT and financial services.

This study will not only examine the role played by the YEP in the Mauritian labour force, but will also generate important and accurate data on its effectiveness, accountability, competency and efficiency for policy makers, the Government of Mauritius, employers, unemployed youth and YEP trainees. The outcomes of this research will also help the authorities to revise and devise new strategies to tackle unemployment and enhance training among those aged between 16 to 24 years.

Problem statement

The Youth Employment Programme is a key strategy to improve the skills of young Mauritians in order to reduce unemployment. It has been running since December 2013. A significant amount of money is spent annually on subsidising the allowances of of young YEP trainees. Also, despite the implementation of the YEP programme, the youth unemployment rate rose to around 25% in 2017, whereby more young women (31.9%) found themselves unemployed compared to young men (19.5%). Even by the first quarter of 2020, unemployment among young people continued to remain high at 25.5% (Statistics Mauritius, 2021). This situation has been described by Tandrayen-Ragoobur and Kasseeah (2013) as a ticking time bomb. Despite the seriousness of this, few assessment and evaluation exercises have been conducted to judge the effectiveness of this programme. Hence, there is an urgent need to investigate the effectiveness of this wage subsidy strategy (YEP) as an effective means of developing employability skills among youth.

Purpose of study

The main aim of this research is to critically examine the effectiveness of the YEP in both equipping young Mauritians to acquire the required labour skills and ultimately, helping them to secure employment. The overall effectiveness of the programme is critically examined through the factors that affect trainees’ satisfaction, their beliefs that the YEP would help them get a job and its actual contribution in terms of increasing their employability.

Literature review

Human Capital Theory

Developed in 1954 by Arthur Lewis, this theory contends that skills and knowledge are primordial for human capital and workforce development (Schultz, 1961). Through education and training, people are able to acquire knowledge and skills which are commonly referred to as capital. Human capital is regarded as an investment in education and training which foster economic growth and develops the workforce while increasing the social and private benefits. (Bowman, 1969; Becker, 1994; Blaug, 1976; Jamil, 2004; Mincer, 1958; Mincer, 1962). Not only do training and education enable the acquisition of knowledge and skills, they also boost employment opportunities for the youth allowing them to gain monetary and non-monetary profits and enlarging their job prospects abroad (Nafukho et al., 2004; Olaniyan et al., 2008). Thus, it is vital to train the youth as employers would rather recruit trained employees than fresh graduates who lack skills and work experience (Mohd Puad, 2015; Mohd Puad, 2018).

Mohd Puad (2018) also posits that employers train their employees with the aim of boosting their productivity, creativity and competitiveness which, in turn, will impact positively on the organization’s profits. The HCT framework is a win-win situation for both the youth and the economy as it not only benefits the youth but also boosts the country’s economy and reduces youth unemployment. The HCT framework explains how individuals may be made more productive; thus, increasing the marginal product of labour. Investment occurs in the form of apprenticeship and training where human resources are assets and output is the economic interest. Benefits are derived by the youth, the economy and the society as a whole. YEPs are based on the belief that investment in human capital is a must to reduce unemployment among the youth. The aim of employment programmes is to enable the youth to join the labour market, get a job and ease the shift from training to employment.

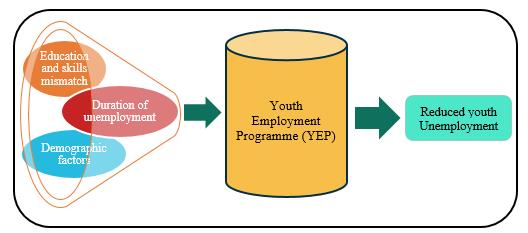

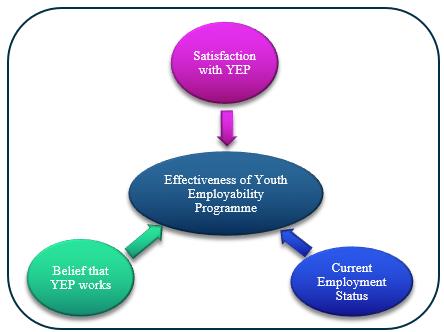

As argued, YEPs are based on the Human Capital Theory. The YEP augments employability skills and directly impacts on the employability chances of the youth. Figure 1 summarises the transformation process through which YEP reduces the impacts of the youth’s background regarded as ‘disadvantaged’ such as gender and long periods of unemployment through its training (to equip youth, for example with intrinsic skills) which eventually increases youth’s employability. However, there are instances when this transformation process may not be effective (Steinberg & Darity 1985).

Empirical evidence

The extent to which demographic aspects affect employment programmes and employability among youth is debatable among the different theories explored. Gender, age and dwellership in particular have impacted on a youth’s likelihood to participate in an employment programme and thereby secure a job. Zenobia (2018) queries the impact of gender on a youth’s likelihood to enroll in an employment programme. Gender is a causal factor in a youth’s likelihood to secure a job post an employment programme is dependent on the country’s focus on gender effect. Popescu and Mocanu (2018) explained that young male adults were more likely to enroll in employment programmes than females in Romania. O’Connell (2002) also found that in Ireland those aged between 25-39 years were more likely to be employed. However, the likelihood that a youth will enrol in an employment programme lowers with age (Popescu & Mocanu, 2018). Dwellership also impacts on a youth’s likelihood to participate in an employment programme and thereby, secure a job. In Kosovo, males from urban regions were enrolled under the Public Employment Services and had higher chances of being employed (Elezaj et al., 2019). In Mauritius, rural dwellers are more prone to undertake vulnerable employment commonly referred to as temporary, contract and entrepreneurial jobs as compared to urban dwellers (Gokhool et al., 2018).

The likelihood that a youth will obtain a job post an employment programme is also determined by the duration the latter spent in unemployment after completion of his/her training. O’Connell and McGinnity (1997) argue that a youth who has enrolled in a training programme has higher chances of securing a job on the short term than on the long term. Moreover, according to the theory of ‘lump of labour fallacy’, Mogomotsi and Madigele (2017) reported that an old employee retiring from work will make place for the youth in the labour market. Therefore, if retirement age is preponed, youth will have more opportunities to enter the labour market. Also, according to O’Connell and McGinnity (1997), the period spent in unemployment negatively impacts the employability of a youth; however, those who have been unemployed for more than 12 months post an employment programme were being employed. This finding is reiterated by O’Connell (2002) who explains that among 1,473 youth in his study, 750 of them were able to secure a job post participation in one of the programmes.

Moreover, youth are mainly interested in high quality programmes which match their field of study (Sherab & Thapa, 2015). The field of study of the youth also influences the probability of a youth to enroll in an employment and thereby secure a job. Hamida, Trabelsi and Boulila (2017) assessed the effect of Active Labour Market Policies (ALMPs) on the employment aftermath of youth who possessed a degree in the Tunisian governorates. Graduate pharmacists, graduate architects and technicians had higher chances of being employed by 21.7%, 34.6% and 5.3% respectively. Those in the medical field though having no significant effect on ALMPs still had more chances of being employed. Youth in paramedical specialties, textile and clothing are 17.4% and 6.83% more likely to be employed respectively. But, sectors such as philosophy, sociology, psychology and language demonstrated a negative effect. However, the science and medical fields showed no effect on a youth’s likelihood to be employable; they were able to secure employment without the help of employment programmes.

To secure a job post an employment programme is the aim of mostly all employment programmes but the nature of the employment obtained is also questionable. Gyampo (2012) explains that the youth in Ghana obtained a 2-year contract job but were made redundant and could not secure a permanent job as those on the National Youth Employment Programme (NYEP) in Ghana were poorly paid. Thus, this programme did not boost employability. According to Rinne and Eichhorst (2015), liberalizing temporary contracts was one way to boost youth employability in Europe but this bore staff turnover consequences which complicated the shift from temporary jobs to permanent employment. The policies to protect fixed term contracts resulted in high youth unemployment (Rinne & Eichhorst, 2015). On the other hand, Hazenberg et al. (2016) also found that lack of motivation, self-confidence and self-esteem are key aspects which prevent youth from succeeding professionally. The quality of the employment programme has a positive effect on employability only if the main aim of the programme does not solely rely in keeping the youth off the unemployment register list (Kluve et al., 2002; Kluve et al., 2016). Most employment programmes are beneficial when youth unemployment is high and if wage subsidy is provided to the organization (Kluve et al., 2002).

Smee et al. (2014) explain that a youth applying for a job and attending an interview should be work ready and is expected to possess intrinsic factors and soft skills such as self-care and resilience: informed traits required for both skilled and unskilled jobs. So, a youth’s ability to obtain a job is neither dependent on his educational qualifications nor on the number of interviews attended but, in fact, depends on other factors as explained above. As such, YEPs not only boost employability but also provide better pay incentives for the youth (Brown et al., 2003). O’Connell and McGinnity (1997) also highlighted the importance of the impact of the duration of a training programme on a youth’s employability. They found no difference between youth who have participated in an employment programme on the long term and those who have not participated in any employment programme. They also propound that employment programmes do not give the assurance of a job over the long term. Sherab and Thapa (2015) argue that trainees enrolled in the Direct Employment Scheme (DES) were not permanently hired as this would mean an additional expenditure for the organization. Instead, organisations expect a subsidy from the government to encourage and boost apprenticeship to help them identify potential employees.

Methodology

Research design

The study used the quantitative approach to collect data. Only those who were currently undergoing training or had previously undergone training through the YEP were targeted. Using random survey technique, 250 questionnaires comprising both open-ended and close-ended items were randomly distributed across existing and former YEP trainees. However, only 214 questionnaires were retained as these did not contain any missing information. Open-ended items were used to supplement the results obtained through the quantitative analysis. Some data were collected through the internet and the rest were collected in person at offices, shopping malls and other public places in Mauritius. An item, ‘Are you currently on YEP or have you been on YEP?, was included to test the respondent’s eligibility to participate in the survey. The rest of the items gathered socio-economic information including employment status, experience as a (former) YEP trainee, programme quality, employability skills acquired through YEP and skills mismatch if any.

Research questions

This research sought to examine the effectiveness of the YEP in Mauritius in terms of youth employability, satisfaction of YEP trainees and their belief that YEP increases employability. Thus, the following three fundamental questions were raised:

- Are beneficiaries of the YEP satisfied with the programme?

- Do YEP trainees believe that the YEP helps them to get a job?

- Does the YEP really enhance youth employability?

Proposed research model

Figure 2 illustrates the research model used for this study. Effectiveness is determined by satisfaction level of trainees, their beliefs and current employment status. The rationale behind using ‘belief’, ‘satisfaction’ and ‘current employment status’ as measures of the effectiveness of YEP is that a programme cannot be sustained unless prospective participants believe that it will work in their favour and they are satisfied with it. Also, it is important to examine its contribution objectively, that is, in terms of employability.

Logit model

The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) was used for data analysis. The logit model was used to measure the relationship of the dichotomous dependent variable with the independent variables. Three logistic regressions were estimated. The dependent variable was derived from the item ‘Are you satisfied with YEP?’ for the first model; ‘Do you think YEP will help or has helped you to get a job? for the second model; and ‘Are you currently employed?’ for the third model. O’Connelle and McGinnity (1997) for instance, used the logit model to predict youth employability in Ireland. The logit model is also useful to rank the impacts of the determinants according to their significance on the dependent variable. The sample for this study comprised 214 participants who were categorised into ‘unemployed’, ‘existing YEP trainees’ and ‘former YEP trainees’. All three models contain the following twelve explanatory variables: age, gender, dwellership, number of interviews, sector of employment, duration of unemployment post YEP training, length of training, sector of training, nature of employment, refusal of YEP placement, quality of YEP training and field of study.

The use of the logistic model is an efficient way of assessing the effectiveness of the YEP. The log odds of finding a job due to the YEP and the log odds of a post YEP trainee actually finding a job are linear combinations of these 12 variables. However, the latter contained observations only from former YEP trainees who were either employed or unemployed (dependent variable). This is the first research that captures youth’s likelihood to secure employment in Mauritius once their YEP training is over. On the other hand, the log odds of YEP trainees’ satisfaction are postulated to be a linear combination of 14 variables, that is, two additional variables were added to the model to control for the effects of allowance under the YEP training and whether YEP trainees would recommend the programme to others. Following the recommendation of other researchers (Field, 2009; Sanmukhiya, 2019) the forced entry method was utilized because the variables used for this study may be considered as valid predictors.

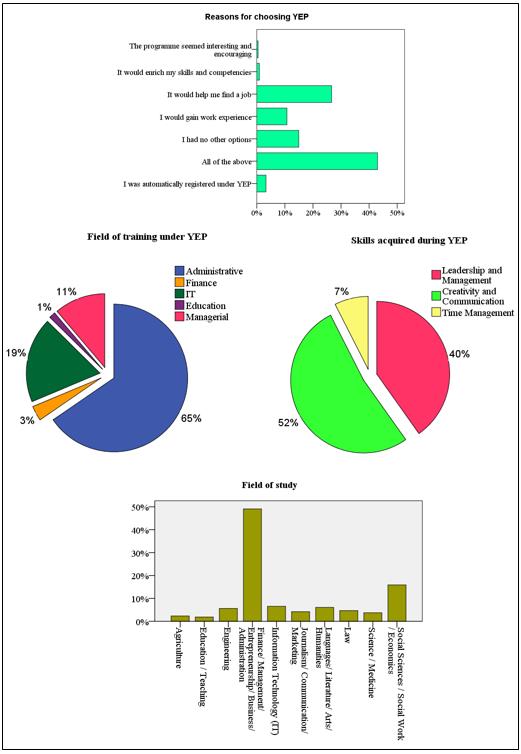

Characteristics of participants

The sample comprised a total of 214 participants. 50% of the sample dwelled in urban areas. Close to half of the sample was aged between 19 to 25 years (48.1%); had undergraduate degrees (69.2%); had completed at least one of the following courses (49.1%)- finance, management, entrepreneurship and business administration; and, had permanent positions at work. Also, 65.4% stated that their field of training under the YEP was Administration while 52.3% said that the YEP work placement had helped them develop their creativity and communication skills. However, due to the minimal numbers of observations for skills acquired during YEP, this variable was dropped from further analysis and is excluded from the logit models.

The majority of the sample was women (75.7%) out of which 52.3% had a bachelor degree. This is in line with other studies which highlight the presence of relatively more women than men with a similar level of qualifications in employability programmes (Hamida, Trabelsi, & Boulil, 2017; Kring, 2017). The rationale behind enrolling in the YEP for 43% of the sample was mostly because they had no other options; the programme seemed interesting and encouraging; it offered them with the possibility of finding jobs; gain some work experience during the training; and enrich their skills and competencies. A minority of 3.3% stated that they had not chosen the YEP in the first place, but instead, were automatically registered in the programme. Figure 3 illustrates the skills, areas, field of study and reasons for choosing the YEP.

Analysis

The Hosmer and Lemeshow test is used to assess the goodness of fit of the logistic models; how well the model fits the data. Table 1 shows that none of the models show poor predictions as p-values for each model exceed 0.05, implying that the models adequately fit the data. Moreover, the log-likelihood values and the parameter estimates converged before the maximum number of iterations were reached which imply that all three models are stable. The iterations varied from 4 to 7 across the models. Model 3 had only 173 participants because the remainder were still in the YEP training. Models 1, 2 and 3 correctly classified around 78.4%, 70% and 92.5% of the participants respectively. For each model, the value of the -2 Log-likelihood is lower than the value of the -2LL when only the constant was included in the model, which indicates that each model predicts the dependent variable more accurately. This is further supported by the Chi-square distribution for each model which is highly significant [Model1: (19) =93.546, p<0.001; Model 2: (17) =60.926, p<0.001; Model 3: (16) = 129.973, p<0.001].

Table 2 displays the Nagelkerke R2and Cox & Snell R2values to gauge the substantive significance for each model. Although the values vary across each measure, they are conceptually the same (Field, 2009). This study chooses to interpret the Nagelkerke R2 values because it is an improvement over the Cox & Snell R2. According to the guidelines provided by Chin (1998), both Models 1 and 2 can be classified as having moderate predictive accuracy whereas Model 3 has substantial predictive accuracy. In terms of collinearity, none of the variables in any of the models have variance inflated factors that exceed 5 and tolerance level consistently exceed 0.2 for all models. Given that all 3 models fulfilled the required methodological ground rules, they may be used to assess the effectiveness of YEP. The next section examines the results of the analysis. All odd ratios are displayed in Table 3.

Findings

None of the factors that capture the effects exerted by the profiles of the respondents on the effectiveness of the YEP were statistically significant. Age, gender and dwellership, for instance, do not affect participants’ satisfaction of the programme or their belief about the YEP helping them to find a job or their likelihood of actually finding a job. Although dwellership does not act as a predictor in any of the models, Gokhool et al. (2018) reported that rural dwellers were more likely to take on vulnerable employment (such as temporary jobs or on a contract basis) as compared to inhabitants of urban regions in Mauritius.

Moreover, factors that were directly related to the YEP were examined. An important finding is that the effectiveness of the YEP as measured through these three binary dependent variables cannot be predicted by the length of training through YEP, whether they had found a job upon completion of the internship and whether they had ever refused an internship through the YEP. However, Sherab and Thapa (2015) highlighted the importance of employment programmes by explaining that employers regard training as being too costly and time consuming. Through employment programmes, organisations are provided a subsidy to provide a work placement and this helps them to identify their potential employees. So, the contribution of the YEP in this regard cannot be underestimated.

Neither trainees’ satisfaction with the programme nor the likelihood of being employed is determined by the number of interviews they took. Smee et al. (2014) argue that number of interviews attended by a youth after his/her employment programme has no effect on his/her ability to secure a job as the latter is expected to be work ready at the interview level and possess all the intrinsic factors and soft skills such as self-care and resilience which are informed traits required for the labour market. Personal and organizational competencies or lifelong learning may serve to increase employability (Civelli, 1998; Evers, Rush, & Bedrow, 1999). Also, Hazenberg et al. (2016) explain that lack of motivation, self-confidence and self-esteem prevent youth from succeeding professionally. However, trainees who attended more than 5 interviews were 2.2 times more likely to believe that the YEP has either helped them or would help them to get a job. Here, it may be argued that a youth gains the interview experience through the number of interviews he/she has attended. They become familiar with what is expected of them in terms of skills as compared to a newbie in the domain and this gives them the advantage (Pheko & Molefhe, 2017). The YEP acts as a facilitator here.

Improved quality of the programme increased both the odds of participants’ being satisfied with the YEP and the odds of believing that the YEP helps in securing a job by 2.4 and 1.8 times respectively (p<0.001). Surprisingly, this highly significant effect of quality on the odds of actually finding a job was non-existent. The quality of the programme did not predict the likelihood of being employed. Kluve and Schmidt (2002) argued that the quality of the training content has a positive impact on employability only if its sole aim is not to keep youth off the unemployment register list. Nevertheless, the quality of the programme boosted participants’ belief and their feeling of satisfaction in the programme which could have triggered their self-confidence to such an extent that it indirectly either helped them to get a job or prepared them better to handle situations related to the labour market such as going for interviews; demonstrating their communication and interpersonal skills; their ability to work under pressure; and stress management. However, the current study does not examine indirect effects.

Work placements that matched the field of study predicted the belief that the YEP could or had helped trainees to get a job (p<0.05). Those who undertook internship in their respective fields of study were 2.3 times more likely to believe that the programme has or would eventually help them get a job than those who did work placements outside their fields of study. However, matching their training to their fields neither made them feel satisfied with the programme nor has helped them to actually find a job (when compared to those who experienced the mismatch). Job placements are in line with the needs of the labour market so their main focus is mainly on the high demand fields. Also, youth who are enrolled in vocational education have greater chances of securing a job compared to those who enter the labour market with academic qualifications. Here work experience is important to secure employment (Mogomotsi & Madigele, 2017). The YEP bridges the gap between education and the labour market in helping youth acquire the requisite skills and gain valuable work experience.

Another finding emerged regarding the duration of unemployment prior to the enrolment of participants in the programme. Those who did not have a job during at most 6 months prior to their YEP placement did not feel satisfied with the programme and did not attribute their employment status to the programme. In contrast, those who were unemployed for less than 6 months prior to their enrolment in the YEP believed that the YEP has or could help them find a job when compared to those who were unemployed for a longer period (p<0.01). The odds were 3 times higher. This aligns with O’Connell and McGinnity (1997)’s findings that the interval spent in unemployment has a negative effect on employability opportunities.

Recommendation is an important aspect of any programme as it ensures its survival. This applies especially in the case of Mauritius where people pay more attention to word of mouth and peer influence. Thus, this element of whether the participants would recommend the programme was added in the model with the dependent variable ‘Are you satisfied with the programme?’ Those who stated that they would recommend YEP were 3.1 times more satisfied than those who said they would not recommend the programme (p<0.01). Thus, the government could launch a team to investigate the reasons why trainees would not recommend YEP to others. This would both improve the programme and, at the same time, attract more potential trainees.

Salary usually influences the level of satisfaction, the belief of whether one can find a job and eventually accepting a job offer. It was hypothesized that the stipend earned during the YEP would impact on the trainee’s level of satisfaction with the YEP. However, the belief that one would get a job after the YEP placement and the likelihood of actually being employed would be more influenced by the salary associated with the job offer instead of the stipend earned under the YEP. The logistic model shows that stipend given to YEP trainees under the YEP scheme did not predict how satisfied they were with the programme. This suggests that satisfaction with the programme is determined by factors other than trainees’ stipend. Similarly, the salary earned by employees did not predict trainees’ beliefs that the YEP has helped or could help them to secure a job. However, the study found that those earning a salary above MUR10000 were around 19 times more likely to accept a job than those whose incomes were up to MUR10000 (p<0.001).

Field of study predicts the satisfaction derived from the YEP (p<0.01). Those who studied science-based subjects (including medicine and agriculture) or finance (including business administration) or humanities (including journalism and communication) were less likely to be satisfied with the programme when compared to those who studied social sciences by 0.24, 0.15 and 0.08 times, respectively. However, trainees’ beliefs in the YEP helping them to get a job and whether they actually get the job are not predicted by their fields of study. Trainees do not regard field of study as a key element when they assess their employability on the labour market. It may be argued that during their YEP placements, they had realised that employers value skills and not their fields of study. Field of study does not ensure that the graduate has developed the required employability skills such as team work, leadership skills, adaptability, patience, emotional control and resilience.

The belief that the YEP has helped or could help get a job and the likelihood of actually being employed were not predicted by the sector where work placement was done. However, those doing their internship in the public sector were 2.6 times more likely to be satisfied with the YEP (p<0.05). This is associated with Mauritians’ way of thinking as Mauritian society has a high esteem for those employed in the public sector, and internship in that sector may justify trainees’ satisfaction.

Nature of employment was included in all models. It consisted of those who took up temporary and permanent employment. Although nature of employment did not influence trainees’ satisfaction of the programme, it predicted the likelihood of being employed (p<0.001) where those who were already employed on a permanent basis were 7.4 times more likely to find a job compared to those who were on temporary employment. Also, compared to those who were unemployed, trainees with temporary employment were 0.25 times less likely to believe that the YEP has helped or would help them to eventually find a job (p<0.05). In Europe, for instance, the government liberalised temporary contracts to enhance employability among youth but this resulted in a huge staff turnover, preventing the youth from moving to permanent jobs (Rinne & Eichhorst, 2015).

Conclusions and Implications

The conclusions are presented as responses to the research questions.

Overall, can we say that YEP is effective?

Trainees’ satisfaction depends on the sector in which work placement was done, quality of the internship programme, field of study and whether they would recommend the YEP to others. On the other hand, trainees’ beliefs about the YEP’s capability to help them get a job were predicted by the number of interviews they had taken, their duration of unemployment before undertaking the programme, whether internship was done in their fields of study, nature of employment and quality of the YEP. Participants were more likely to be employed if the job was permanent with a salary exceeding MUR 10000.

Given that the statistically significant factors related directly to the YEP such as quality of programme, sector of work placement and nature of work were far fewer than those factors that did not affect satisfaction, belief or employability such as whether trainees had eventually found a job upon completion of internship, length of YEP training and whether they had ever refused a YEP placement, it may be argued that the YEP has failed in its objectives to provide the support that it initially purported. Also, given that, for all those except in the field of social sciences, the YEP was not a satisfying experience, it implies that the programme needs major restructuration to cater for those who studied, for instance, medicine or journalism. However, the contribution that the YEP might have had in eradicating the effects of demographic factors such as age, gender and dwellership on youth satisfaction, beliefs and employability cannot be ignored.

Policy and practical implications

The government should set up a performance evaluation system which assesses the youth’s performance at work every 6 months to enable it to identify the weaknesses of the programme and the participants in order to institute amendments and long term outcomes (Smee et al., 2014). Also, the marketing of the YEP should be more visible and youth-oriented; for example, advertisements of the programme in social networking sites such as Facebook, Instagram and Snapchat. The government should emphasize on vocational training to encourage the youth to opt for vocational jobs instead of focussing mainly on administrative and clerical jobs. This aspect should be included in the YEP in order to provide a larger variety of job placements.

Suggestions for further studies

This research provides interesting and valuable insights into the impacts of the YEP in Mauritius and further research may be undertaken by government administrators to upgrade the YEP to impact positively on youth employability. This study may suffer from selectivity bias as participants self-select themselves into the YEP. Hence, future studies can comapre participants of the YEP and non-participants. Additionally, studies based on the qualitative approach where for instance focus group interviews among YEP trainees can be conducted, triangulated by semi-structured interviews of employers and people who never participated in the YEP to give more extensive insights into the problems associated with the YEP. Exploring these aspects can contribute to the field of knowledge on the demand side especially on the efficacy of such YEPs in addressing youth employability issues.

Acknowledgements

The author(s) declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

Agwani, K. (2014). Rural livelihood and Youth Employment: Case Study of Local Enterprises & Skills Development Programme in Elmina Municipality of the Central Region of Ghana. Unpublished Masters dissertation. Institute for Social Development, University of the Western Cape. http://hdl.handle.net/11394/3849

Almendarez, L. (2011). Human capital theory: Implications for educational development. Proceedings of Belize Country Conference November 16 -17, 2010. https://www.open.uwi.edu/sites/default/files/bnccde/belize/conference/papers2010/almendarez.html

Becker, G. S. (1994). Human Capital: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis with Special Reference to Education, Third Edition. University of Chicago Press: Chicago Print.

Blaug, M. (1976). The Empirical Status of Human Capital Theory: A Slightly Jaundiced Survey, Journal of Economic Literature, 14(3), 827-855. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2722630

Brown, P., Hesketh, A., & Williams, S. (2003). Employability in a Knowledge-driven Economy. Journal of Education and Work, 16(2), 107-126.

Center for Human Services Research. (2017). Best Practices to Enhance the Employability of Opportunity Youth: A Synthesis of the Available Literature. University at Albany, Albany: New York. https://www.albany.edu/chsr/Publications/CAPRIemployer surveyreport0917%20(1).pdf

Chin, W. W. (1998). The Partial Least Squares Approach to Structural Equation Modeling. In G. A. Marcoulides (Ed.), Modern Methods for Business Research. New Jersey. London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates

Civelli, F. (1998). Personal competencies, organizational competencies, and employability. Industrial And Commercial Training, 30(2), 48-52.

Dobrić, A. L (2018). Periodic evaluation of the local youth employment initiative programmes, Social Inclusion and Poverty Reduction Unit, Government of the Republic of Serbia. Serbia. ocijalnoukljucivanje.gov.rs/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Periodic_evaluation_of_the_local_youth_employment_initiative_programmes_2018.pdf

Elezaj, L., Gjipali, A., & Ademaj, S. (2019). The Impact on Employment of Active Labour Market Policies: An Evaluation of Public Employment Services (PES) in Kosovo. Southeast European Journal of Economics and Business, 14(1), 61-71.

Evers, F., Rush, J., & Bedrow, I. (1999). The bases of competence: skills for lifelong learning and employability. Choice Reviews Online, 36(10), 36-5809-36-5809.

Field, A. (2009). Discovering Statistics Using SPSS (and Sex and Drugs and Rock'n'Roll) (Third ed.). London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Gokhool, S., Kasseeah, H., & Tandrayen-Ragoobur, V. (2018). Vulnerable employment in Mauritius: experience of an upper-middle-income country. International Journal of Development Issues, 17(2), 187-204.

Gokulsing, D. (2018). Globalisation, Higher Education and Youth Unemployment: The Case of Mauritius. Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Managing Organisations in Africa (ARG 2017), Mauritius.

Gyampo, R. (2012). Youth Participation in Youth Programmes: The Case of Ghana’s National Youth Employment Programme. The Journal of Pan African Studies, 5(5), 13+. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A306357763/AONE?u=anon~c9e77a43&sid=googleScholar&xid=cebf16ee

Hamida, N., Trabelsi, S., & Boulila, G. (2017). The impact of active labor market policies on the employment outcomes of youth graduates in the Tunisian governorates. Economics, Management and Sustainability, 2(2), 62-78.

Hazenberg, R., Lashley, J., & Denny, S. (2016). Enhancing Youth Employability in the Caribbean: Lessons from UK NEET Programmes. Proceedings of the 17th Annual SALISES Conference - Youth employability and social exclusion. Hilton Hotel, Barbados.

Jamil, R. (2004). Human Capital: A critique. Jurnal Kemanusiaan, 2(2), https://jurnalkemanusiaan.utm.my/index.php/kemanusiaan/article/view/133

Kluve, J., Puerto, S., Robalino, D., Romero, J. M., Rother, F., Stöterau, J., Weidenkaff, F., & Witte, M. (2016). Do Youth Employment Programs Improve Labor Market Outcomes?, A Systematic Review, [Ebook]. Germany: IZA - Institute Labor of Economics DP No. 10263. https://ftp.iza.org/dp10263.pdf

Kluve, J., & Schmidt, C. (2002). Can training and employment subsidies combat European unemployment? Economic Policy, 17(35), 409-448.

Kring, S. (2017). Gender in employment policies and programmes: what works for women (pp. xi, 56 p.). Geneva: Employment Policy Department, International Labour Office.

Mincer, J. (1958). Investment in Human Capital and Personal Income Distribution. Journal Of Political Economy, 66(4), 281-302.

Mincer, J. (1962). On-the-Job Training: Costs, Returns, and Some Implications. Journal Of Political Economy, 70(5, Part 2), 50-79.

Mogomotsi, G., & Madigele, P. (2017). A cursory discussion of policy alternatives for addressing youth unemployment in Botswana. Cogent Social Sciences, 3(1), 1356619.

Mohd Puad, M. H. (2015). "The role of employability skills training programs in the workforce of Malaysia". Open Access Dissertations. 520.https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/open_access_dissertations/520

Mohd Puad, M. H. (2018). Obstacles to Employability Skills Training Programs in Malaysia from the Perspectives of Employers’, Educators’ and Graduates’ Perspective. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 8(10), 952-972.

Nafukho, F., Hairston, N., & Brooks, K. (2004). Human capital theory: implications for human resource development. Human Resource Development International, 7(4), 545-551.

O'Connell, P. (2002). Are They Working? Market Orientation and the Effectiveness of Active Labour-Market Programmes in Ireland. European Sociological Review, 18(1), 65-83.

O'Connell, P., & McGinnity, F. (1997). What Works, Who Works? The Employment and Earnings Effects of Active Labour Market Programmes among Young People in Ireland. Work, Employment & Society, 11(4), 639-661.

Olaniyan, D. (2008). Staff Training and Development: A Vital Tool for Organizational Effectiveness. European Journal of Scientific Research, 24(3), 326-331. http://www.eurojournals.com/ejsr.htm

Pheko, M., & Molefhe, K. (2017). Addressing employability challenges: a framework for improving the employability of graduates in Botswana. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 22(4), 455-469.

Popescu, M. E., & Mocanu, C. (2018). Do Apprenticeships Increase Youth Employability in

Romania? A Propensity Score Matching Approach. OECONOMICA, 14(1), 215-225. https://econpapers.repec.org/RePEc:dug:actaec:y:2018:i:1:p:215-225

Rinne, U., & Eichhorst, W. (2015). International Labour Organization, 2015. Promoting Youth Employment Through Activation Strategies. Research Report Series. Geneva: International Labour Office.

Sanmukhiya, C. (2019). A Study of Effect of Demographic Factors on E-Government Divide in The Republic of Mauritius. Humanities & Social Sciences Reviews, 7(6), 436-446.

Schultz, T. (1961). Investment in Human Capital. American Economic Review, 51(1), 1-17. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1818907

Sherab, K., & Thapa, R. (2015). Impact Assessment of the Youth Employment Promotion Programme (YEPP). Institute of GNH Studies. Royal University of Bhutan.

Smee, A., Hibbert, T., McNeil, B., Johns, R., & North, J. (2014). The Young Foundation - Social Research Unit at Dartington. (2014). Ready For Work - The capabilities young people need to find and keep work and the programmes proven to help develop these. London: Impetus – The Private Equity Foundation. https://www.impetus.org.uk/assets/publications/Report/2014_09-Ready-for-Work.pdf

Statistics Mauritius. (2021). Labour force, Employment and Unemployment – First quarter 2020.

Ministry of Finance, Economic Planning and Development https://statsmauritius.govmu.org/Documents/Statistics/ESI/2020/EI1528/LF_Emp_Unemp_1Qtr20.pdf#search=unemployment

Steinberg, S., & Darity, W. (1985) Human Capital: A Critique. The Review of Black Political Economy,14(1), 67-74.

Tandrayen-Ragoobur, V., & Kasseeah, H. (2013). Youth Unemployment in Mauritius: The Ticking Bomb, Proceedings of ICEFMO: Handbook on The Economic, Finance and Management Outlooks. PAK Publishing Book. http://www.conscientiabeam.com/ebooks/ICEFMO-240-714-735.pdf

Zenobia, I. (2018). Lessons Learned from Youth Employment Programmes in Kenya. Birmingham UK. University of Birmingham. https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/handle/20.500.12413/14425

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.