Abstract

Drama education is still a rather young field of science. Thus, there is an obvious need to conceptualize the elements and factors related to drama education fostering children’s creativity. What kind of learning environment supports children's creativity? Which aspects of drama education nurture children's creativity? Children’s creativity is often referred to as ‘little c creativity’, LCC. Subjectivity is an intrinsic character when defining children’s creativity since it is not determined by society. The article aims to perceive and build a theory of tuition supporting children’s creativity in the context of drama education. The objective of this theory-based article is to characterize the terminology of creativity in drama education. Based on prior research, the purpose of the article is to construct a model of tuition fostering children’s creativity. This theoretical model is contemplated through drama education. In a creative learning environment of drama the children are provided with rich experiences and their active role in learning is emphasized. Interaction is an essential part of learning process making learning itself a social activity. Creative environment supports children’s imagination and inner motivation. In addition, the atmosphere is permissive. These elements also create a potential for group creativity. According to research, the need to support children’s creativity is obvious. Furthermore, children’s creative development should be considered on two levels: the individual creativity of each pupil and the group creativity of the whole class. Drama education has the potential to nurture pupil’s creativity through its experiential, social and children-activating nature.

Keywords: Creativity, drama education, creative pedagogy, creative environment, teacher education, Finnish teacher education

Introduction

Postmodern knowledge society places new demands on schools all over the world; students need to be creative, have the ability to cooperate in group processes and acquire information. This is the expertise students should master to succeed in life and work in the 21st century (see Sawyer, 2006; University of Phoenix Research Institute, 2011). A broad study made in the United States (Kim, 2011) surveyed the development of creativity from the early 1990s to now. According to the study, intelligence has increased significantly during the past two decades, whereas creativity and creative thinking have decreased. The study indicated that children's ability to produce ideas and be open to new ideas increases until they reach the age of nine. After that, these abilities remain quite stable for about a year until they begin a steady decline. Children’s curiosity and open-mindedness followed the same path. Kim (2011) proposes that schools should encourage creative thinking and expression. There should be more opportunities available for pupils to be active and have critical discussions instead of drill exercises and standardized testing. Pupils become less creative when they experience the pressure of conventionality.

Problem Statement and Research Questions

Various questions emerge from the results introduced above. In this article, we first aim to examine the concept of creativity and the key factors related to it. The purpose of this article is to determine the elements of a learning environment supporting children’s creativity by combining research and theory of creativity with the theory of drama education.

We seek to contemplate and outline the following questions based on prior research and self-reflection:

- What kind of learning environment supports pupils’ creativity in schools?

- Which aspects of drama education nurture pupils’ creativity?

This theoretical review is part of a research project undertaken at the University of Helsinki, Department of Teacher Education. The research project is focused on classroom drama teaching practices (e.g., Toivanen, Pyykkö, & Ruismäki, 2011; Toivanen, Antikainen, & Ruismäki, 2012; Toivanen, Mikkola, & Ruismäki, 2012; Toivanen & Pyykkö, 2012a, 2012b). This article outlines some aspects of drama education that nurture children's creativity. Naturally, the model is a hypothetical draft that is based on the theories of creativity and drama education.

Creativity

Creativity is a multi-dimensional and complex phenomenon. It is difficult to measure and one of the most difficult psychological concepts to define. (e.g., Kousoulas, 2010; Kurtzberg, 2005; McCammon et al., 2010; Sawyer, 2012a.) Nonetheless, it is possible to find some similarities from the various definitions of creativity.

Researchers usually approach the field of creativity from one of the four generally acknowledged locations or expressions: a creative person, product, process or environment (Lemons, 2005; McCammon et al., 2010, Uusikylä, 2012). While studying a creative person, the focus is on the creative personality. In turn, a number of researchers have stressed the transformational abilities of the creative process. Environment refers to the milieu where creativity occurs. (Lemons, 2005.) Traditionally, creativity is defined through the result of the process, i.e., a product; making a creation the subject of a study (Craft, 2005). A creative product can be an invention as well as piece of art, theory, skill or habit. It is known that creativity does not always manifest a certain concrete result. Even a creative idea can be a creative invention (Craft, 2005; Uusikylä & Piirto, 1999). In this article, we approach the field of creativity from the concept of creative process that also defines creative behaviour and creative thinking as creative processes.

In addition to the traditional creativity elements of a creative person, product, and process, Csikszentmihalyi (1996; 1999; see also Brinkman, 2010; Lemons, 2005; Sawyer, 2003; 2012a) stresses the significance of the environment. This perspective emphasizes the importance of environment in creativity; creativity is described as a process and an inseparable part of its surrounding culture. Craft (2005) summarizes the definition of creativity is focused either on the location, production or effect of creativity. Creativity can manifest subjectively, collectively or actively. In other words, creativity can also be present in a group or a process. A production, on the other hand, can be either an idea or a physical product. Furthermore, the effect of creativity can be both global and local. The common factor for these pre-described definitions is that producing new and different ideas is a part of creativity (Craft, 2005; Kudryavtsev, 2011). Creativity is an ability to develop something novel and adapt to new situations. Unusual solutions alongside originality are seen as inevitable parts of creativity (Hackbert, 2010; Lemons, 2005).

The majority of prior creativity research has focused on the actions of creative geniuses (see e.g., Craft, 2005; Gardner, 1993) and many of the definitions of creativity presented in this article are based on the same concepts of creativity. However, challenges that have arisen from modern technology and the innovative economy have created the need for ‘everyday’ creative thinking. This alteration is also seen in the field of research for creativity where the manifestation of creativity is also studied thoroughly nowadays (see e.g., Brinkman, 2010; Craft, 2005; 2012; Lin, 2011; Paulus & Dzindolet, 2008; Sawyer, 2012a).

We have chosen Craft's (2001, 45) concept of ‘little c creativity’, LCC, as our main concept to define children’s creativity and creative learning. With the term LCC, Craft (mm. 2001; 2005) separates everyday creativity from ‘big C creativity’, BCC, (Kudryavtsev, 2011), which usually refers to the actions and productions of creative geniuses. BCC creativity has to meet two criteria: originality and adding significant meaning to a larger group of people. Children's creativity often differs from adult's creativity due to its subjectivity; children's creativity rarely meets the criteria of BCC creativity (see e.g., Craft, 2001). As stated above, LCC creativity (Craft, 2001; 2005) describes children's creativity. Educators see children as naturally creative. Children are always open to new experiences and have a habit of being interested in everything new (Lin, 2011).

Subjectivity is an intrinsic characteristic of children’s creativity. The novelty in children’s creative ideas is not determined by society, but by their prior knowledge (Kudryavtsev, 2011). Craft (2005) adds imagination as a relevant part of children’s creativity. Children’s creativity is always inventive but also mostly imaginative. Some aspects of the imagination may even be considered as an implicit part of creativity (Craft, 2005).

Drama education and creativity

Drama education (classroom drama) is defined in our research project as both an art subject and a teaching method. Classroom drama uses elements of the theatre art form for educational purposes for students of all ages. Within drama studies all students work as a group using drama conventions (freeze-frames, teacher-in-role, etc.), to devise short pieces of fiction. Fictional roles, time and space help the pupils to communicate their understanding in an aesthetic way to themselves and their fellow participants (Rasmussen, 2010; Neelands & Goode, 2010; Neelands, 1984; 2009). Drama incorporates elements of theatre to facilitate the student’s cognitive, physical, social and emotional development and learning. Classroom drama is a multisensory mode of teaching and learning (Bolton, 1998, 198–200; Neelands, 1984; Toivanen, 2012a). Drama work covers a broad area of techniques incorporating physical movement, vocal action, and mental concentration, which traditional classrooms have lacked in quantity and quality in the past.

A number of studies confirm that in many ways drama education can tackle the future educational challenges that school systems are facing (e.g., Cooper, 2010; Catterall, 2009; Gallaher, 2001; Toivanen, 2009, 2002; Wright, 2006). The use of drama in education can be seen as an alternative to scripted schooling and an answer to the challenges of the postmodern knowledge culture, which aims for deeper conceptual understanding by preparing students to create new knowledge (Toivanen, 2012a; 2012b). Drama education represents the concepts of experiential (Kolb, 1984) and socio-constructive learning (Liu & Matthews, 2005; Rasmussen, 2010).

The purpose of drama is to create an interactive and positive learning environment in which the participants' construction of knowledge and learning takes place through creative and interactive social relationships. By alternately working in a role and as themselves, the learners acquire operating experiences and create new knowledge of the phenomena that are being reviewed. Drama offers opportunities for learners to create their own drama representations. In drama, the learners can express their own creative thinking and reflect on it with other group members. The concept of socio-constructive learning stresses the development of identity and the perception of goals’ values. A long-term goal in drama education is to help learners understand themselves, others and the world in which they live (see Bowell & Heap, 2001; Heikkinen, 2002; 2004; Joronen et al., 2011; Joronen et al., 2008; Laakso, 2004).

Creative pedagogy

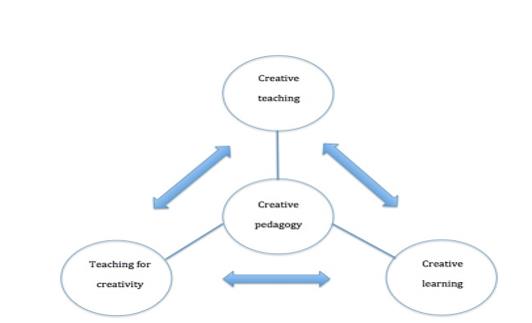

The concept of creative teaching is problematic due to several existing meanings. Various researchers have approached the concept of creative teaching by focusing on either creativity that occurred in schools or creative actions performed by teachers (Besançon & Lubart, 2008; Craft, 2005; Jeffrey, 2006; Joubert, 2001; Saebø et al., 2007; Sawyer, 2004, 2006; Shaheen, 2010). Lin (2011) describes creative teaching from three different perspectives: creative teaching, teaching for creativity and creative learning, referring to them as creative pedagogy (see Figure 1).

According to Lin (2011), the first perspective, creative learning is an essential part of creative pedagogy since its focus is on children’s action. Creative learning embraces children’s intrinsic curiosity in tuition (Lin, 2011). Typically, drama activities offer immediate experiences to the participants. Learning is approached through observation and exploration which are, according to Craft (2005), essential for creative learning.

The second perspective, creative teaching, focuses on teaching and teacher’s actions (Lin, 2011, see also Sawyer, 2004, 2006). Lin (2011) refers to creative teaching as a creative, innovative and imaginative approach to teaching (cf. e.g. Craft 2005). Sawyer (2004; 2006) emphasizes a creative teacher’s ability to use improvisational elements in tuition. When teaching creatively, the teacher utilizes the rules of improvisation by living in the moment and acting spontaneously. The teacher may have planned the lesson one way, but a creative teacher has the courage to take the ideas that have arisen from the pupils and change the lesson to finish it in another way (Sawyer, 2004, 2006). The third and last perspective, teaching for creativity, considers the significance of a creativity-supporting environment (Lin, 2011). The environment denotes both the external and social context that supports and inspires learning. A key element for both perspectives is the open-minded atmosphere towards creativity created by the teacher. This is the teacher’s open-mindedness towards creative ideas and behaviour, pupil-centricity, flexibility, and the appreciation of independent thinking. Teaching for creativity is a child-centred approach emphasizing learners’ responsibility for and control of their own learning. Teaching for creativity encourages children to ask questions, argue, discuss their thoughts and actively engage in their own learning. Teaching for creativity aims for creative learning and the development of a creative person (Craft, 2005).

Teacher’s creative action can also act as a model encouraging children to act creatively themselves (Craft, 2005; Jeffrey, 2006). Jeffrey and Craft (2004) have discovered three elements related to creative teaching and teaching for creativity. First, teachers both teach creatively and for creativity subject to the appropriate circumstances. Second, teaching for creativity may occur spontaneously in situations where it was not intentional. Third, they accentuate that teaching for creativity is more likely to emerge from the context of creative teaching (Jeffrey & Craft, 2004). In addition, both Craft (2005) and Jeffrey (2006) emphasize that although creative teaching does not necessarily lead to children’s creativity, it offers both teacher and pupils suitable contexts to be creative. By using their own creativity at work, teachers create opportunities for pupils to maintain and improve their creative learning. In addition, teachers can produce a creative learning environment.

Creative environment

Creativity always depends on the surrounding environment and the beliefs and ideologies held by the people within it. Creativity does not occur in isolation. Researchers use the term Zeitgeist to describe the cultural, economic and political times affecting a creative person (e.g., Lemons, 2005). Positive and supportive attitudes towards creativity do not hinder creative development. However, a positive atmosphere alone is not enough to support the growth of a creative person. Creative children need support and encouragement from adults, mainly from their parents and teachers. The environment should be inspiring and accent freedom. Evaluation and measures of effectiveness are perpetual barriers to creative development (Uusikylä & Piirto, 1999).

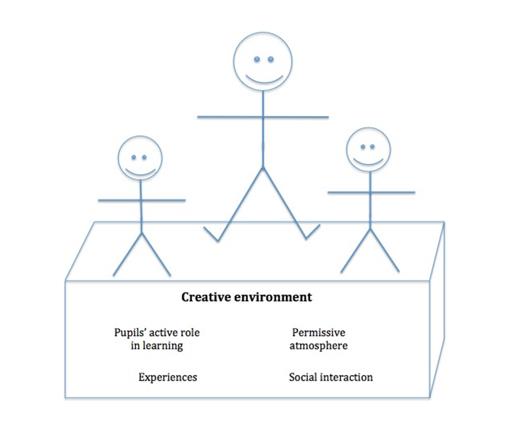

The purpose of this article is to outline a model drama education programme that supports pupils’ creativity. We are especially interested in examining different parts of creative learning in a creative learning environment that is enabled by drama. What kind of prerequisites for a creative environment can we define where drama both fosters and develops pupils’ creative learning? We have shown the key factors of creative learning in Figure 2. This draft is based on a theoretical review.

We delineate the context of drama tuition (creative environment) as a stage where there is space for individual creativity and particularly collective group creativity to emerge. The stage represents the creative environment that is a base for pupil’s creative development offered by the teacher. The key feature for creative drama processes is the use of teaching methods that emphasize pupils’ active role in learning (creative thinking). Experiences offer material to develop creative thinking processes. In order to support the development of pupils’ creative thinking, the teacher should enrich pupils’ imagination by offering experiences in abundance.

We outline drama as a pupil-active, experiential and socio-constructive way of learning. Drama activities offer opportunities for pupils to express their ideas; in a creative environment, pupils work in a permissive atmosphere. Due to the positive atmosphere, pupils do not need to be afraid of failure or performance-focused evaluations that inhibit creativity. Drama enables group creativity through its social interaction between pupils (co-actors). Group creativity and interaction skills progress in group activities when pupils learn to co-operate with different people.

In our draft, pupils perform on the stage as ‘actors’. Drama work requires imagination and interaction skills from the pupils. Imagination that is natural for children enables rich creative actions. A positive learning atmosphere, necessary to a creative process and creative thinking, is also important for drama activities. While spending most of their waking hours at school, children should have opportunities for spontaneous and imaginative play (Toivanen, Komulainen & Ruismäki, 2011). Although children are creative by nature, their creativity can be fostered and nurtured at school by offering them a creative environment in which to learn (Kim, 2011). Drama education can be a tool to teach children and improve children’s creative learning, if it covers the parts we determine next.

Creative learning

In this article, creative teaching refers to teacher’s action, i.e., teaching, with its goal to support and develop children’s creativity through drama. An essential part of creative teaching is to offer a creative learning environment (Figure 2). In the context of drama education, creativity is not defined as a characteristic of an individual but of a whole group. Drama with its active inquiry process offers space for both a teacher’s creative teaching and pupil’s creative learning. In creative drama learning children’s action is the key element. Creative learning emphasizes children’s intrinsic curiosity in tuition (Lin, 2011). Creative process and group creativity are essential features of creative drama learning. Creative process includes the definitions of creative thinking and flow experiences related to learning. In addition, group creativity refers to drama learning as a collective action.

Creative process and flow in the context of drama learning

Creative process traditionally follows different phases from problem definition to information gathering, followed by conceptual combination eventually leading to an evaluation of ideas (Csikszentmihalyi, 1999; Uusikylä, 2002; see also Mumford et al., 2012). In drama education, action describes all phases of the process. In order for drama activities to be successful and creative, they require children to have courage to act and think in an unconventional way (Toivanen, 2002).

It is possible to find some contradictions in definitions of creativity and especially creative process in three ways. First, a person can either refrain from or break traditional boundaries. Second, divergent solutions may create contradictions. Third, the tension between creative disorder and organized order can be seen both individually and collectively (Tardif & Sternberg, 1988). These contradictions may also appear in educational drama processes when other group members resist creative ideas. Furthermore, the contradictions determined by Tardif and Sternberg (1988) can be seen when comparing children’s actions with adult’s behaviour. Teachers may find it difficult to understand pupils’ imagination and creativity since they do not obey the frames and rules made by adults. This makes creative teaching challenging from the teacher's point of view. The complexity and diversity of creative processes in the classroom drama make it challenging for teachers especially at the beginning of their drama teaching careers (see Toivanen, Pyykkö, & Ruismäki, 2011; Bowell & Heap, 2010; Toivanen, Rantala, & Ruismäki, 2009; Wales, 2009; Sawyer, 2004; 2006.) Therefore, developing the skills for creative teaching (disciplined improvisation in teaching) should be part of teacher education.

Gardner (1993) classifies five creative processes: problem solving, constructing a theory, developing a genre, planned creative performance and situational creative performance. When regarding children’s creativity through the concept of LCC (instead of BCC), children’s creativity represents all of Gardner’s (1993) definitions of creative processes. During drama activities, pupils solve problems when they attempt to work out a fictional situation or create something novel with the drama methods being used. Pupils construct a new theory or concept and examine the relations between various concepts through drama processes. Planned and situational creative performance naturally requires an audience. In drama education, planned performance is a theatre play that is known and practised in advance and performed by a person or a group. Classroom drama can be defined as a situational creative performance in which a person and the group live in the moment and have the ability to react spontaneously (Gardner 1993). In the context of drama education, it is more unusual to develop a new genre.

Because the base of drama education is in theatre arts, it is natural to compare drama action with a creative process between actors as described by Nemiro (1997). Acting is always a social process; even during a solo performance, the actor interacts with at least the director. A group of pupils involved in drama can be described similarly. Social interaction between group members and the teacher is a prerequisite for drama work (Neelands & Goode, 2010). Nemiro (1997; see also Cohen, 2002) states that actors’ have an urge for spontaneity while also acting in the frames and the guidelines set by the script and the director. He separated three steps in the creative process of the actors. The first step includes overall preparation when actors improve their skills in general. During the next step, the actors rehearse for a certain performance. The last step is unique for actors and other performers: the complete act is simultaneously a creative process and a final creative product (Nemiro, 1997). Compared to Nemiro’s (1997) definition, drama action is more spontaneous and the group is more focused on situation-specific and improvised solutions (Toivanen, 2012a).

Csikszentmihalyi (e.g., 1996) has defined a psychological concept of flow, a mental state that can be reached during a creative process. After performing a task that required full involvement, it is typical for an actor to have a feeling of enjoyment that has been called flow. Flow is not likely to be recognized at the moment of performing the activity, because the feelings of enjoyment occur only after finishing the activity. Afterwards, flow can be identified as a sense of losing track of time and self-consciousness in addition to acting effortlessly.

Flow can be achieved by focusing all the energy to the activity. The activity must have clear goals throughout. Furthermore, concentration must be fully focused on the activity without external distractions. Flow is impossible to reach with a fear of failure. On the other hand, in flow the activity keeps the actors too involved to be concerned about failing (Csikzentmihalyi, 1996).

When performing drama exercises, there are two main premises that must exist in order for the actors to reach flow. First, the atmosphere must be permissive, and second, the challenge of the activity must be appropriate for the pupils and their abilities (Csikszentmihalyi, 1996). Flow is enabled when there is a balance between task challenges and group skills. If the challenge is too high compared to the skills required, actors may feel anxious or that the activity is too easy or boring. When drama activities are motivating and suitably challenging, they create a deep commitment towards the activity that can even make pupils lose track of time. The features of flow can emerge during drama exercises when pupils fully concentrate on the activity.

Creative thinking

Creative thinking is studied as a cognitive process (Bacanlı et al., 2011; Mumford et al., 2012). Bacanlı et al. (2011) emphasize the cognitive characteristics of creative thinking. Although creative thinking includes both cognitive and affective thinking features, most of it consists of various cognitive processes. According to Mumford et al. (2012), creative thinking contains complex processes making it impossible to examine through only one model. They have studied creative thinking as a process through thinking strategies, knowledge base, or by combining these two aspects. They consider problem solving as an example of a creative thinking process (Mumford et al., 2012).

Creative thinking is often linked with original and unique ideas. Runco and Acar (2012) separate the concept of divergent thinking from creative thinking as an opposite to analytic, convergent thinking. However, divergent thinking only has the potential to be creative thinking. Original ideas do not entirely represent creative thinking, but they are only a part of the cognitive and complex phenomenon of creative thinking (Runco & Acar, 2012). Although divergent thinking is often distinguished from creative thinking, in this article we solely use the term of creative thinking to refer to both divergent and other creative thinking. An example of this creative thinking that occurs during drama processes is problem solving as determined by Mumford et al. (2012).

Acting in drama processes requires plenty of rapid subconscious thinking. Gladwell (2005) has compared the power of subconscious thinking to improvisation theatre. In his opinion, improvisation is a great example of intuitive thinking about complicated solutions. Intuitive thinking means a reaction based on immediate insights. Gladwell (2005) continues to say that depending on the situation our mind makes decisions between the conscious and the subconscious. The decisions can be made based on an extremely small amount of knowledge and sometimes the hasty conclusions may be entirely unconscious. Actions can be justified without the actor being able to describe or explain them. Gladwell (2005) has noticed that our society often demands grounds for our decisions and that is why people rarely trust the conclusions of their subconscious thoughts. Nevertheless, Gladwell (2005) recalls accepting and respecting the mystery of rapid decision-making, since the power of thinking is to know without knowing why.

Group creativity

According to Sawyer (2012a), creativity researchers can be divided into two groups based on the research approach. The individual approach studies creative people and their creative ideas and processes, whereas the socio- cultural approach relies on the idea of people as an inseparable part of the surrounding environment. A cultural definition of creativity contains both of these perspectives: individual creativity surrounded by time, environment, and the new phenomenon of group creativity as a part of a social context (Sawyer, 2012a; Turner, 2008). According to creativity researchers, creativity is not necessarily a property of an individual; it can also be a property of a group. This group creativity is simply defined as a creative process or product created by a group, organization or another ensemble (Sawyer, 2003; 2012a).

Group creativity differs from individual creativity by nature; it is interactive and dialectic. However, the creative process of creative individuals diverges from the creativity manifested collectively, even though the creative individuals are in connection with the existing social and cultural environment (Sawyer 2003; 2012b). Researchers do not want to limit group creativity as a sole property of artists, but also see it as a phenomenon seen in everyday life, as in children’s play (e.g., Lobman, 2003; Dunn, 2008; Sawyer, 1997) and organizations (e.g., Turner, 2008). In group creativity, creative ideas are an outcome of collaboration. Solving problems in organizations and learning in the classroom are also examples of group creativity (Sawyer, 2003; 2012b).

Kurtzberg (2005) points out that studying group creativity often includes an attempt to understand the creative potential of the group. Since group potential is dependent on individual skills within the group, studies have aimed to discover the relation between individual capacity and group creativity (Kurtzberg, 2005). Pirola-Merlo and Mann (2004) state that very little research has been done on the individual contribution to the creative process performed by a group. They explain the lack of research with the challenge of generalizing because individual creative solutions always depend on the situation and task.

On the other hand, the problematic relation between individual and group creativity relies on the variable definitions of creativity. Group creativity is different from individual creativity, so studying them together as one object is challenging. Therefore, research is still focused on group creativity as a whole phenomenon without distinguishing the individual contributions of single group members in the creative process (Kutzberg, 2005; Pirola-Merlo & Mann, 2004). The same collective aspect is seen in drama learning; the drama process is a result of creative communication, thinking and acting between the members of the group involved. Group creativity and the concept of creativity as a process are essential for drama learning (Sawyer, 2003).

Conclusions

Creativity is as a multi-dimensional concept. In the history of creativity research, sometimes the emphasis has been on the individual perspectives; sometimes the relevance has been on the society. On the one hand, creativity is mostly seen as a creative event, work or action, or even as a creative product. On the other hand, in the context of child education the focus has been on the creative environment or creative process. The latest research has indicated the importance of the environment to enhance creativity. In this article, we have also highlighted the environment as an essential element of creativity.

Jeffrey and Woods (2003) emphasize the teacher’s creativity and ability to offer a creative learning environment with creative experiences. The learning environment at school can either support or limit creativity. We concur with Craft (2005), who stresses the significance of encouragement in nurturing creativity. The environment should encourage pupils to exceed their own and others’ expectations and reward them when doing so. Creativity evolves in an open and safe atmosphere, whereas compulsion and discipline decrease creativity. Several researchers speak on behalf of an open and safe learning environment and an atmosphere to help children enjoy school and achieve better learning results (Craft, 2005; Jeffrey & Woods, 2003; Uusikylä & Piirto, 1999).

Creativity researchers have recently become more interested in group creativity (see Coate & Boulos, 2012; Cooper & Jayatilaka, 2006; Kurtzberg, 2005; Sawyer, 2003; 2012a). In this article, we are curious about group creativity in drama. Research results indicate that group creativity has much potential due to its collective nature in inventing ideas. New inventions are more likely to occur in a group, when a group member’s observation can lead to another member’s idea. Social interaction is seen as a relevant impact on creative and innovative process (Kurtzberg, 2005; Sawyer, 2012a, 232; 2012b; Turner, 2008).

Active drama processes always include creative thinking as a part of the creative process. All creative processes are based on thinking which can be seen from the classification of creative processes defined by Gardner (1993). Creative thinking is opposite to conventional and non-creative thinking and creative thinking is essential to develop novel and original ideas (Bacanlı et al., 2011).

In order to support pupils’ creativity, drama should give them opportunities to develop both individual and group creativity in the school learning environment. Drama tuition should offer experiences to enrich pupils’ imagination and give chances for pupils to practice their interaction skills. In the future, people will be expected to have a variety of skills. Schools should respond to these future demands by enhancing children’s creativity, independent thinking, and interaction skills. Well-executed drama tuition should offer an opportunity for interactive and social learning situations, where creative teaching, teaching for creativity and creative learning are in close relation to each other. Drama offers individuals not only space but also a way to develop social skills and enjoy the support of a group. Through these elements, pupils can gain understanding and develop their potential in an open and safe environment. The teacher’s role is to support these educational processes and arrange opportunities to enhance creativity. In this article our aim has been to outline theoretically some parts of creative pedagogy, specifically creative learning, in the context of drama education. As a future research object, this theoretically formed model of creative drama learning should be examined in practice.

Acknowledgements

The author(s) declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

Bacanlı, H., Dombaycı, M. A., Demir, M., & Tarhan, S. (2011). Quadruple thinking: creative thinking. Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences, 12, 536–544. DOI:

Besançon, M., & Lubart, T. (2008). Differences in the development of creative competencies in children schooled in diverse learning environments. Learning and Individual Differences, 18, 381–389. DOI:

Bolton, G. (1998). Acting in classroom drama: a critical analysis. London: Trentham Books.

Bowell, P., & Heap, B. S. (2001). Planning process drama. London: David Fulton Publishers.

Brinkman, D. J. (2010). Teaching creatively and teaching for creativity. Arts Education Policy Review, 111, 48–50. DOI:

Catterall, J. S. (2009). Doing well and doing good by doing art: the effects of education in the visual and performing arts on the achievements and values of young adults. Los Angeles/London: Imagination Group/I-Group Books.

Coate, K., & Boulos, A. (2012). Creativity in education: challenging the assumptions. London Review of Education, 10(2), 129-132. DOI:

Cohen R. (2002). Acting one. Boston: McGraw Hill.

Cooper, C. (Eds.) (2010). Making a world of difference, A DICE resource for practitioners on educational theatre and drama. Retrieved on December 1, 2012 from http://www.dramanetwork.eu/file/Education%20Resource%20long.pdf

Cooper, R. B., & Jayatilaka, B. (2006). Group creativity: the effects of extrinsic, intrinsic, and obligation motivations. Creativity Research Journal, 18(2), 153–172. DOI:

Craft, A. (2001). ‘Little c creativity’. In A. Craft, B. Jeffrey & M. Leibling (Eds.), Creativity in education (pp. 45–61). London: Continuum.

Craft, A. (2005). Creativity in schools: tensions and dilemmas. Abingdon: Routledge. DOI:

Craft, A. (2012). Childhood in a digital age: creative challenges for educational futures. London Review of Education, 10(2), 173–190. DOI:

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1996). Creativity: flow and the psychology of discovery and invention. New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1999). Implications of a system perspective for the study of creativity. In R. Sternberg (Eds.), Handbook of creativity (pp. 313–335). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. DOI:

Dunn, J. (2008). Playing around with improvisation: an analysis of the text creation processes used within preadolescent dramatic play. Research in Drama Education: The Journal of Applied Theatre and Performance, 13(1), 55–70. DOI:

Gardner, H. (1993). Creating minds: an anatomy of creativity seen through the lives of Freud, Einstein, Picasso, Stravinsky, Eliot, Graham, and Gandhi. New York: Basic Books.

Gallaher K. (2001). Drama education in the lives of girls: imagining possibilities. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. DOI:

Gladwell, M. (2005). Blink: the power of thinking without thinking. London: Penguin.

Hackbert, P. H. (2010). Using improvisational exercises in general education to advance creativity, inventiveness and innovation. US-China Education Review, 7(10), 10–21.

Heikkinen, H. (2002). Draaman maailmat oppimisalueina. Draamakasvatuksen vakava leikillisyys. [Drama worlds as learning areas - the serious playfulness of drama education]. Jyväskylä: University of Jyväskylä.

Heikkinen, H. (2004). Vakava leikillisyys. Draamakasvatusta opettajille. [The serious playfulness of drama education. Drama Education for teachers] Helsinki: Kansanvalistusseura.

Jeffrey, B. (2006). Creative teaching and learning: towards a common discourse and practice. Cambridge Journal of Education, 36(3), 399–414. DOI:

Jeffrey, B., & Craft, A. (2004). Teaching creatively and teaching for creativity: distinctions and relationships. Educational Studies, 30(1), 77–87. DOI:

Jeffrey, B., & Woods, P. (2003). The creative school: a framework for success, quality and effectiveness. London: Routledge. DOI:

Joronen, K., Rankin, H. S., & Åstedt-Kurki, P. (2008). School-based drama interventions in health promotion for children and adolescents: Systematic review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 63(2), 116-131. DOI:

Joronen, K., Konu, A., Rankin H. S., & Åstedt-Kurki, P. (2011). An evaluation of a drama program to enhance social relationships and anti-bullying at elementary school: A controlled study. Health Promotion International, 26(1), 5-14. DOI:

Joubert, M. M. (2001). The art of creative teaching: NACCCE and beyond. In A. Craft, B. Jeffrey & M. Leibling (Eds.), Creativity in education (pp. 17–34). London: Continuum. DOI:

Kim, K. H. (2011). The creativity crisis: the decrease in creative thinking scores on the Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking. Creativity Research Journal, 23(4), 285–295.

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Kousoulas, F. (2010). The interplay of creative behavior, divergent thinking, and knowledge base in students’ creative expression during learning activity. Creativity Research Journal, 22(4), 387–396. DOI:

Kudryavtsev, V. T. (2011). The phenomenon of child creativity. International Journal of Early Years Education, 19(1), 45–53. DOI:

Kurtzberg, T. (2005). Feeling creative, being creative: an empirical study of diversity and creativity in teams. Creativity Research Journal, 17(1), 51–65. DOI:

Laakso, E. (2004). Draamakokemusten äärellä. Prosessidraaman oppimispotentiaali opettajaksi opiskelevien kokemusten valossa [Drama experiences. The learning potential of the process drama according to the teacher students.] Jyväskylä: Jyväskylä University Printing House.

Lemons, G. (2005). When the horse drinks: enhancing everyday creativity using the elements of improvisation. Creativity Research Journal, 17(1), 25–36. DOI:

Lin, Y.-S. (2011). Fostering creativity through education — a conceptual framework of creative pedagogy. Creative Education, 2(3), 149-155. DOI:

Liu, C. H., & Matthews, R. (2005). Vygotsky’s philosophy: Constructivism and its criticisms examined. International Education Journal, 6(3), 386–399.

Lobman, C. (2003). What should we create today? Improvisational teaching in play-based classrooms. Early Years: An International Journal of Research and Development, 23(2), 131–142. DOI:

McCammon, L. A., O’Farrell, L., Saebø, A. B., & Heap, B. (2010). Connecting with their inner beings: an international survey of drama/theatre teachers’ perceptions of creative teaching and teaching for creative achievement. Youth Theatre Journal, 24, 140–159. DOI:

Mumford, M. D., Medeiros, K. E., & Partlow, P. J. (2012). Creative thinking: processes, strategies, and knowledge. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 46(1), 30–47. DOI:

Neelands, J. (1984). Making sense of drama. A guide to classroom practice. Oxford: Heineman Educational Publishers.

Neelands, J. (2009). Beginning drama 11–14. Second Edition. London: David Fulton Publishers.

Neelands, J., & Goode T. (2010). Structuring drama work. A handbook of available forms in theatre and drama (Second Edition). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nemiro, J. (1997). Interpretive artists: a qualitative exploration of the creative process of actors. Creativity Research Journal, 10(2&3), 229–239. DOI: 10.1207/s15326934crj1002&3_12

Paulus, P. B., & Dzindolet, M. (2008). Social influence, creativity and innovation. Social Influence, 3(4), 228–247. DOI:

Pirola-Merlo, A., & Mann, L. (2004). The relationship between individual creativity and team creativity: aggregating across people and time. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 25, 235–257. DOI:

Rasmussen, B. (2010). The ‘good enough’ drama: reinterpreting constructivist aesthetics and epistemology in drama education. Research in Drama Education: The Journal of Applied Theatre and Performance, 15(4), 529-546. DOI:

Runco, M. A., & Acar, S. (2012). Divergent thinking as an indicator of creative potential. Creativity Research Journal, 24(1), 66–75. DOI:

Saebø, A. B., McCammon, L. A., & O’Farrel, L. (2007). Creative teaching–teaching creativity. Caribbean Quarterly, 53(1–2), 205–215. DOI:

Sawyer, R. K. (1997). Pretend play as improvisation. Conversation in the preschool classroom. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Sawyer, R. K. (2003). Group creativity. Music, theatre, collaboration. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Sawyer, R. K. (2004). Creative teaching: collaborative discussion as disciplined improvisation. Educational Researcher, 33(2), 12–20. DOI:

Sawyer, R. K. (2006). Educating for innovation. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 1, 41–48. DOI:

Sawyer, R. K. (2012a). Explaining creativity. The science of human innovation. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Sawyer, R. K. (2012b). Extending sociocultural theory to group creativity. Vocations and Learning, 5, 59–75. DOI:

Shaheen, R. (2010). Creativity and education. Creative Education, 1(3), 166–169. DOI:

Tardif, T., & Sternberg, R. (1988). What do we know about creativity? In R. Sternberg (Eds.), The nature of creativity (429– 440). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Toivanen T. (2002). Mä en olis ikinä uskonu ittestäni sellasta. Peruskoulun viides- ja kuudesluokkalaisten kokemuksia teatterityöstä [I would have never believed in this from myself. Theatre experiences of 5th and 6th graders.] Acta Scenica 9. Helsinki: Teatterikorkeakoulu.

Toivanen, T. (2009). Teatterilähtöiset menetelmät ja nuoren identiteetti. [Theatre-based methods and identity] In Gröndahl L., Paavolainen T. and Thuring A. (Eds.), Näkyvää ja näkymätöntä [Visible and Invisible] (pp. 271–287). Helsinki: Teatterintutkimuksen seura.

Toivanen, T. (2012a). Drama Education in the Finnish School System: Past, Present and Future. In Niemi, H., Toom, A. & Kallioniemi, A. (Eds.), Miracle of Education. The Principles and Practices of Teaching and Learning in Finnish Schools (227– 236). Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

Toivanen, T. (2012b). Pohdintaa draamakasvatuksen perusteista suomalaisessa koulukontekstissa: opetusmenetelmä vai taideaine [Drama education in Finnish school context: teaching method or art subject.] Kasvatus, 43(2), 192-198.

Toivanen, T., Antikainen, L., & Ruismäki, H. (2012). Teacher’s perceptions of factors determining the success or failure of drama lessons. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 45, 555–565. DOI:

Toivanen, T., Komulainen, K., & Ruismäki, H. (2011). Drama education and improvisation as a resource of teacher student’s creativity. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 12, 60–69. DOI:

Toivanen, T., Mikkola, K., & Ruismäki, H. (2012). The challenge of an empty space: pedagogical and multimodal interarction in drama lessons. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 69, 2082–2091. DOI:

Toivanen, T., Rantala, H., & Ruismäki, H. (2009). Young primary school teachers as drama educators – possibilities and challenges. Teoksessa H. Ruismäki & I. Ruokonen (Eds.), 1st International Journal of Intercultural Arts Education Conference Post-Conference Book (129–140). University of Helsinki: Research Reports 312.

Toivanen, T., Pyykkö, A., & Ruismäki, H. (2011). Challenge of the Empty Space: Group Factors as a Part of Drama Education. Procedia: Social and Behavioral Sciences, 29, 402-411. DOI:

Toivanen, T., & Pyykkö, A. (2012a). Group Factors as a Part of Drama Education. The European Jounal of Social & Behavioral Sciences, 2(2), 150-168.

Toivanen, T., & Pyykkö, A. (2012b). Challenge of the Empty Space: Group Factors as a Part of Drama Education part 2. Procedia: Social and Behavioral Sciences, 69, 2289–2298. DOI:

Turner, M. E. (2008). Introduction. Social influence and creativity: setting the stage for inventiveness. Social Influence, 3(4), 223–227. DOI:

University of Phoenix (2011). The ten main skills for future workforce. (http://www.phoenix.edu/education-in- the-21st-century/21st-century-skills/10-skills-for-the-future-workforce-part-1-of-5.html read 22.4.2013)

Uusikylä, K. (2002). Voiko luovuutta opettaa? [Can you teach creativity?] In P. Kansanen & K. Uusikylä (Eds.), Luovuutta, motivaatiota, tunteita. Opetuksen tutkimuksen uusia suuntia [Creativity, motivation, emotions. New directions in teaching research] (42–55). Jyväskylä: PS-kustannus.

Uusikylä, K. (2012). Luovuus kuuluu kaikille [Creativity is for everyone]. Jyväskylä: PS- kustannus.

Uusikylä, K., & Piirto, J. (1999). Luovuus. Taito löytää, rohkeus toteuttaa [Creativity. A skill to find, courage to act]. Jyväskylä: Atena.

Wales, P. (2009). Positioning the drama teacher: Exploring the power of identity in teaching practices. Research in Drama Education, The Journal of Applied Theatre and Performance, 14(2), 261–278. DOI:

Wright, P. R. (2006). Drama education and development of self: Myth or reality? Social Psychology of Education, 9(1), 43–65. DOI:

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.