Abstract

In drama education theories of agency and ownership are implicit, as active participation is a central condition of drama action. In this article a teacher-researcher examines students’ individual and collective agency in collaboration during one playmaking project with an international group of 13–14-year-old students. Research question: How does students’ agency develop, and ownership strengthen in the collective teacher-student collaboration process during the playmaking project? The chronological and narrative analyses were based on the teacher-researchers’ observation, the playmaking material and video or audio-recorded lessons. Discussions with the teachers and the students participating in the project compiled the data. The student’s agency was analysed and classified during playmaking sessions by applying analytical tool of Rainio (2008), which was based on sociocultural theory. The development of the students’ agency is illustrated as a diagram showing emergence of the students’ passive, constructive and resisting initiative behaviour during the performance-making process. The teacher-researcher’s narrative describes the crucial events of the process and reflects on the student/teacher interaction and challenges of teaching. By resistance and critical attitude, the students tested their power and possibilities to influence in the project. Simultaneously the students’ ownership strengthened and initiative and responsibility taking increased. Conducting an ensemble in creating demanded a special pedagogical orientation: readiness for an open dialogue with students, transformation of the teacher’s role and a willingness to adjust to the process of learning.

Keywords: Drama education, collaborative playmaking, agency, ownership

Introduction

Development of students’ agency has been one of the central themes in educational research. In traditional schooling contradictions between students’ agency and teacher’s need to control have seemed to be unsolvable as the teacher needs to give up control in the classroom, otherwise students can’t develop active agency (Jackson, 1990; McNeil, 1986; Rainio, 2008). Because agency is relational and reciprocal, students need to be treated as active subjects in order to broaden their agency. This demands widening the students’ position, giving ownership of practice to the students and adjustment of the teacher’s role (Edwards, 2005; Rainio 2008; Kumpulainen, Krokfors, Lipponen, Tissari, Hilppö, & Rajala, 2010).

Agency has been defined various ways, depending on the theoretical frame through which it has been investigated. Agency is a central concept in the sociocultural theory of learning based on Vygotski (1978). Agency is defined i.e. as a will to act, to experience and to exist (Emirbayer & Mische, 1998). It means an individual’s or a group’s feeling that we are doing things, which make a difference, that things do not just happen to us. Agency is often associated with creativity, questioning and opposing matters considered as self-evident and looking for unconventional ways of action (Kumpulainen et al., 2010.)

Agency is a complex and contradictory process of interaction with material resources, social institutions and the collective efforts of individuals (Rainio, 2010). Therefore, in order to capture this process it is important to analyse agency related both to the individual and to the collective activity the individuals are part of (Rainio 2010; Edwards & Mackenzie, 2008).

Ownership is a core concept of student-centred learning. The concept of ownership illustrates, how the experiences of learning become personally meaningful. Ownership evolves in questions of autonomy: who owns learning (Rainer & Matthews, 2002). Personal investment, engagement, responsibility, and empowerment constitute criteria of the presence of ownership in individual students or an entire class when working with drama (Swick, 1999).

Anna Pauliina Rainio (2010) conducted an ethnographic research project of student agency in play-world activity in early education settings and developed methodological framework based on sociocultural theory for video-based narrative interaction analysis for studying student agency. This frame and classification of student agency (Rainio, 2008, 2010) is applied in this research. The research (Rainio, 2008, 2010) indicate that play- and drama- based pedagogies offer great potential for developing educational spaces that help teachers and children dealing with contradictory requirements of schooling. However, the engaging in the unconventional activity of play-world and enacting student agency was very challenging (Rainio, 2010.)

The object of this study is to apply and assess Rainio’s (2008, 2010) classification of student agency in a practice based research (Smith & Dean, 2009) setting: teacher-researcher’s analyses of collective/individual participation processes of a Devised performance-making project. The article considers the development of the students’ agency and ownership in the performance-making project experienced by and looked through the lenses of a teacher/researcher.

Devising is a thematic approach to theatre, based on improvisation and experimenting. It is a process for creating performance from scratch by the group without a pre-existing script (Heddon & Milling, 2006). Besides using the concept of devising, playmaking, play-building and collective drama/theatre techniques to develop original performance work in collaboration with students (Lang, 2002; Nelson, 2011).

The case presented in this article consists of one environmental performance project about climate change, which was carried out in 2010 with 13- to 14-year-old students at an international school in Belgium (N=14). The idea of devising the performance was that the common experiences and ideas about climate change expressed by the group were transformed to the performance. In the performance-making project described in this article the special intention of teaching was to encourage students’ active participation in decision making and to put students in charge of as many aspects of the creative collaboration and production as possible.

The teacher-researcher’s perspective characterizes the observation and analyses of the students’ agency and ownership in this study. The students’ agency is looked at as a situational and relational collective social action and behaviour. Students’ agency is assumed developing in interaction with classmates and being reciprocal in the teacher/student relationship. Agency is seen as a process rather than a state, an observable social action and behaviour, which can be evaluated by teachers and a collaborative group of young people. Agency is understood related to the concepts of engagement and ownership with the ideals of individual choice, freedom, intentionality, empowerment and cultural transformation.

Supporting students’ agency and ownership in teaching drama

In drama education theories of agency have long been implicit, as the focus in drama is on the performance, action and engagement (Wright, 2011). According to research drama education supports expansion of students’ active agency. Collaborative play-creating and ensemble based drama enable positive youth development and development of self-efficacy (Baere & Belliveau, 2007; Neelands, 2009). Play-world activities make it possible to profit from student resistance and develop students’ active agency (Rainio, 2008). Drama enables us to look at young people as having potential rather than being at risk. In drama, resistance and risk can be thought of as engaging and providing opportunities for growth and development (Borden, 2006; Wright, 2011).

Devised theatre as a collaborative theme based approach of making a performance offers a site for productive critical pedagogies and great learning potential for cognitive, social and affective domains for the participants (Lang, 2002, 2007; Perry, 2011). Devising and playmaking are optimal tools for facilitating the development of community of active participation among students and between students and teachers (Nelson, 2011). Student-centred learning processes develop authoritative and accountable dispositions in the students. The teacher has a central role in improving the practice and giving space for students’ active agency and ownership of learning at school (Kumpulainen et al., 2010). It is only possible to support students’ social learning, enhance students’ active agency and ownership by giving up control and distributing power in practice.

Conducting artistic collaboration as drama at school is not a simple task. Collaborative teaching of drama requires transformative leadership, which emphasizes the participants’ relationships and individual engagement (Österlind, 2010; Lehtonen, 2013). The teachers applying creative and dialogic teaching in drama must have the capacity to manage unrest, uncertainty and unpredictable situations (Heikkinen, 2005; Toivanen, Rantala & Ruismäki, 2009; Toivanen, Komulainen & Ruismäki, 2011). However, it is only possible to learn these capacities by practice. Critical inquiry of practice helps with confronting issues of power and control, which evolve in collaboration in the classroom (Larrivee, 2000).

Research Question

How does students’ agency develop and ownership strengthen in the collective teacher-student collaboration process during the performance-making project?

Purpose of the Study

In this article the concept of agency is applied and tested as a tool for analyses and evaluation of students’ participation process in the case of a collaborative devised performance-making project. The concept of agency is used to illustrate the process of collaboration: students’ participation, engagement and development of ownership in the collaborative process of the devised performance project.

This research article is part of an ethnographic work based action research project, where I as a teacher-researcher was investigating my own work when applying integrative teaching methods of drama education: improvisation, playmaking and performance-creating in education for a social and ecological sustainable future (Lehtonen, 2012; 2013). In participatory performance projects about climate change and future, I have tested as a teacher-researcher my opportunities in drama education to act on values of social and cultural transformation, how I could engage and empower the students in practice (Lehtonen, 2012; 2013).

Research Methods

The aim of the study to hermeneutically understand the participation process, improve and evaluate the performance-making project resembles work based action research (Mills, 2007; Costley, Elliot, & Gibbs, 2010). The concepts of practice-led research and research-led practice (Smith & Dean, 2009) describe the intertwining relationship between ethnographic research and practice and the double role of the teacher and researcher. The observations of the students’ agency were made while teaching and the reflective field-notes written after the lessons. The interest of research and observation guided the planning of the project.

The research project (Lehtonen, 2012) as a whole has a methodological background in autoethnography as a self-study, observing, writing reflective research notes, consideration of the teacher-researcher’s position and the context of collaboration (Muncey, 2010; Pinnegar & Hamilton, 2011). The desire to understand and interpret the participation processes from the teacher/researcher’s restricted point of view derives from hermeneutic phenomenology and (Gadamer, 1976; McManus Holroyd, 2007).

The research data used for analyzing the development of the students’ agency consists of the teacher-researcher’s extensive field notes, video and audio-recorded lessons and the students’ material for producing the performance. The ethnographic discussions with the teachers and the students with whom the performance project was conducted and all the material of the theatre project were compiled in the data. The main methods of data analysis were a qualitative chronological and narrative analysis (i.e., Lawler, 2002; Webster & Mertova, 2007) of the collaborative process of playmaking.

Agency as an analytic tool

The issue of student agency and ownership evolved within the practice-based research process and the analysing process of the student participation in the challenging collaboration of making the performance. The concept of agency was chosen for evaluation and analysis of the students’ participation process while analysing the data after the performance project.

The classification of the students’ agency of this research was based on the sociocultural theory of agency (Vygotski, 1978) and derived from empirical research conducted by Anna Pauliina Rainio (2008). Rainio (2008) invented this classification for observing and analyzing individual agency in the participation process of a narrative Playworld activity with 7-year-old children, where analyses were made by the observing participant.

According to Rainio (2008) agency in social practices can be developed a) through transforming the object of activity and through self change b) through responsible and intentional membership and through resistance and transformation of the dominant power relations. Rainio (2008) typified agency in three categories: 1) passive, 2) responsive and 3) initiative. The crucial issue is that an initiative aims to have an effect on the flow of the events around the participant. By staying passive or responsive regarding the ongoing activity, one chooses not to participate in defining the rules and nature of the activity itself. Responsive orientation means answering the question, when asked. Making an initiative can be a physical act, verbal contribution or being involved in planning (Rainio, 2008).

Rainio (2008) divided initiative agency into four types: constructing, supporting, deconstructing and resisting. The supportive and constructive initiatives are directed towards creating, sustaining or sharing something that the class does. Deconstructive and resistant initiatives are where the participant tests the limits of the activity or the other participants or chooses not to take part (Rainio, 2008). In this case study the observation and the analyses were made by the teacher- researcher and the results were approximate estimates. The results describe the teacher’s reality, how he/she can look at the process and make remarks about the students’ agency.

The case – A devised performance project with an international class

Brussels in Belgium with a multinational group of 13- and 14-year-old secondary school students (N=14). The whole playmaking project lasted three months and approximately 48 lessons of different subjects were used for the process of preparing the performance from the beginning until the final performance and one feedback session afterwards.

This cross-curricular performance project was about climate change and it integrated mainly drama, music and visual art. These subject teachers worked intensively together. English, geography, ICT and gym class teachers had a minor role in supporting the project as some material for the performance was prepared during those lessons.

The objective of the performance project derives from education for a sustainable future. The students were about to investigate climate change by artistic methods of Devising. The Devising method emphasizes the exploration of participants’ ideas and realities with the goal of developing their voices and visions of the world and bringing them to the audience. The intent was to give an opportunity for the participants to experience their being shown and their voices being heard by the audience and having a chance to influence the attitudes of the audience about climate change. That was how students could take part in the process of trying to change or alter the general unsustainable development of our culture (Lehtonen, 2012).

The other goal of the project was to create an ensemble and promote students’ engagement and active participation and give students as much responsibility of the project as possible. The applied method of Devising aims at artistic democracy: The goal was to encourage active participation, give real and equal possibilities to take part in artistic creation and the decision-making processes of performance-creating (Oddey, 1994).

The students of the class

When I suggested having the integrative collaborative performance project, the other teachers thought that it was a good idea especially for this class of students. The teachers described the class as very challenging with problematic group dynamics having problems fitting in together and divided into national groups.

The four different national groups had been integrated together as a class half a year prior to the project starting. The class was not familiar with the working culture of creative collaboration. The tutors of the class informed me about the problematic power relations and differences in working orientation between the different nationalities.

The teacher-researcher

The scope of the analysis was mainly conducted through the teachers’ lenses with the perspective of teaching. The interpretations of the collaboration process were formed in the process of introspection and retrospection of the teacher-researcher and in dialogue with the participants: students and especially other teachers involved and research literature.

I worked as the drama teacher for the whole class during the project. This was my second year working as a teacher at this international school. I knew some of the students before the project started. I had eight years teaching experience, during which I had conducted different kinds of drama performances. This was my second time combining drama and research with an integrative project and my first time at an international secondary school.

I as the teacher-researcher was responsible for producing data, gathering, analysing and the reporting process. Although my aim was to loosen the roles and reduce the teacher’s control, the student/teacher roles and power dynamics influenced the cooperation during the performance- creating process. The observation and the analyses were based mainly on, what I observed and experienced while teaching and reflected after the lessons. I assumed I was not able to have an objective outsider’s point of view, nor observe in detail the individual behaviour of each student or fully observe how my habituated practices affected students’ behaviour. However, the discussions with the teacher colleagues and focus group of students, the intention of having observer- ethnographer’s lenses and later watching the video-recorded lessons and listening discussions gave new insights to the process.

Analysing process of the students’ agency

The holistic narrative analyses of the process were constructed after managing the overall data: watching, listening and transcribing the lessons and the discussions in chronological order and writing summaries about the happenings of each lesson. The narrative analysing process consisted of selecting the main episodes of the process, reflecting on and searching for the evidence of the development of the challenging episodes and critical turning points during the whole playmaking project (Lawler, 2002; Webster & Mertova, 2007).

The narrative of the collaborative participation process of this playmaking project was first written and published (Lehtonen, 2013) with the emphasis of the teaching process and its challenges. For this research article the narrative analyses of the development of the students’ agency and ownership were finalized after the chronological analyses of the development of the collective agency. Table 1. presents a summary of the happenings during each episode of the playmaking project.

After the narrative analyses each lesson of the whole project was analysed several times in detail and the individual agency was typified and coded. The teacher-researcher’s observation and analyses were not exact but approximate. The assessment of the amount of typified agency was estimated and rough. In The primary data used for the analyses of the specific episode together with the classification of the students’ agency in five categories: passive, responsive, resistant, deconstructive, constructive and supportive are presented in the end of the article (Table 2).

The students’ agency was typified during each lesson, as how the teacher-researcher made remarks on their agency. Quite often the students’ agency was classified as two or three different agencies as the behaviour varied during the lessons. When there was a remarkable change in the structure of the lesson, the lessons were separated into two episodes. The explanations of the happening of each episode are offered in Table 1.

The students’ agency was first classified in six different types including responsive agency according to the classification of Rainio (2008), but the division was not trouble-free. It seemed not possible to make a clear distinction between responsive and constructive agency as there were not many situations without an idea, suggestion given or an assumption of students’ active participation. At first the students’ agency was typified as responsive, when I didn’t note any remarkable or usable initiatives, the students seemed not to make any real effort to create the common performance.

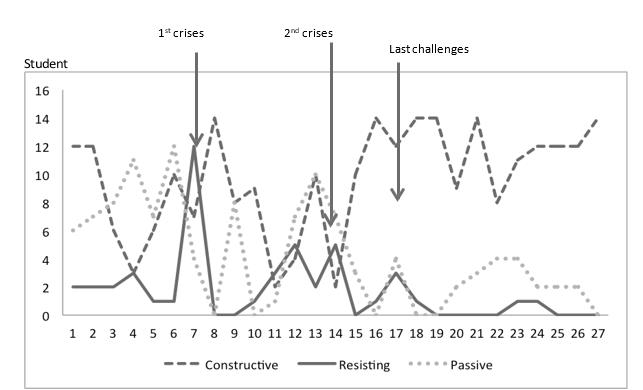

After several analyses and classifications, when I noticed that the depth of the students’ engagement was visible and evident in decreasing passive behaviour, I didn’t find it necessary to include the responsive class in the classification anymore. When the students’ took responsibility and were really engaged and concentrated on working, they were no more passive. In addition, as the students’ agency was rarely supportive or deconstructive, those classes didn’t seem to be remarkable for understanding the development of the students’ ownership, they are not included in the Figure 1. However, the classification in five categories (passive, responsive, resistant, deconstructive, constructive and supportive) are shown in the Table 2.

Findings

To capture the development of the students’ agency within the complex and contradictory interaction process during the performance-making project, the individual and collective participation processes are presented both as a diagram (see Figure 1) and a narrative. The teacher- researcher’s narrative describes the collective process and the development of the ownership. The narrative chronicles the student/teacher interaction and reflects on challenges of teaching. The subtitles of the narrative point out the critical turning points and draw attention to the different objects of the student ownership during the process. Figure 1. illustrates development of the students’ active agency classified as constructive and resisting initiatives and passiveness during each lesson evaluated by the teacher/researcher.

In the Figure 1. the development of the students’ individual/collective agency is illustrated in lines showing approximate amount of students showing constructive and resisting initiatives and passiveness during each lesson or episode (numbers 1 - 27 at the bottom of the diagram) evaluated by the teacher/researcher. For clarification of the analyses of the participation process, a summary of the happenings of each episode/lesson (Table 1.) and a table of the detailed division of the students’ agency in each lesson (Table 2.) are offered.

Constructive initiative agency means a verbal contribution or a physical act or creating some material. Complaining or critical behaviour was classified as resisting. When classified as being passive in the activity of preparing the performance it meant often focusing on something else other than working on having fun with classmates etc.

While the students behaved passively and seemed to be frustrated, their resisting initiatives increased. By resisting the students got more actively involved, concentrated better on the project and passiveness decreases. The process of engagement began with resisting and transformed to constructive activeness. The crises in student/teacher collaboration were turning points, when the students were most resisting and the continuation of the project was questioned.

By challenging the decisions they tested, if their opinions were taken seriously. The students tested their ownership: if they could have an influence on the process, in the content of the performance and the working schedule. Additionally, they checked everybody’s engagement in performing. The turning points of change in the students’ engagement and ownership are clarified in detail in the teacher-researcher’s narrative - the collaboration process of making a performance.

Teacher-researcher’s narrative - the collaboration process of making a performance

The devising principle of the project was that the common experiences and ideas about climate change expressed by the group were transformed to the performance. The intention of teaching was to encourage students’ active participation in decision making and to put students in charge of as many aspects of the creative collaboration and production as possible.

Beginning - ownership of the theme

The project started with a short project presentation and discussion with the students. Every student of the group expressed that they wanted to participate in the performance project, even if they didn’t seem to be really enthusiastic about the idea. They behaved rather passively and were quiet.

Music and the music teacher had a big role in the performance. Students were asked to write poems about climate change, which should serve as lyrics for songs. We started by writing down students’ thoughts and ideas about climate change. A drama contract about rules for collaboration was negotiated and everybody signed the drama contract and agreed on the rules of creative collaboration without any real resistance or critical discussion.

Brainstorming activities were conducted with physical exercises and improvisation games, which did not work out very well. Several students in the group seemed to be unable to concentrate or behave in the empty space of the classroom. The students didn’t seem to be ready to improvise or act and they were not happy with improvisation practices and restless and chaotic behaviour. I had to stop the improvisation practices and conduct less socially demanding narrative activities.

The great challenge at the beginning of the whole project was how to motivate the passive and restless group of students and introduce the methods of working and performance creating in a motivating way. The students didn’t listen to me. They didn’t seem to find it important or relevant to know, what was about to happen. The students didn’t work hard for or take seriously the scriptwriting tasks. I made proposals according to the students’ ideas and thoughts expressed during the brainstorming exercises. The proposals were later voted on among the group.

1st crisis in collaboration – ownership of the performance

Creative collaboration of plot and script creating was anything but simple. After the brainstorming sessions the students were not satisfied with the project, no one was eager to share ideas and the group had difficulties in concentrating on working and behaving. The students complained about the project to their tutors. Some students said that they would prefer filmmaking to playmaking. The students claimed that the performance plan wasn’t made according to their opinions. The students asked, if they could withdraw from the project.

I pondered what we should do. Cancelling the whole project didn’t appear to be a good idea or a relevant option, but we couldn’t continue without careful consideration of the students’ opinions. The students had the power to destroy the project, if they wanted. I presented options of the plot and structure of the performance and the proposals were voted on. Some students got really inspired about the negations. They spoke about a strike and asked for a big party after the performance. After negations, and discussing the realistic options, everyone in the group signed a commitment to the project. The students got seemingly active, they suggested an ice breaking game and they were engaged to plan the scenes in groups.

The students of the case were not used to having such an active role and taking responsibility at school. They were used to studying under control, with highly structured teaching and being rather passive especially when it came to academic subjects. The other teachers’ attitudes, different teaching cultures with norms of control and authority seemed to influence the general atmosphere and students’ attitudes and challenged the collaboration. The teachers had different views of, how to get students to work harder and motivated. Some teachers slightly involved in the project would have liked to have stronger control over the students by teacher evaluation or threatening them with assessments or punishments.

My way to solve the situation was to start to lean on the group’s capacity as the source of solutions, finding the ways to collaborate. I as the teacher had to understand that the success of the project was genuinely dependent on the students and our collaboration. A compromise of the performance by combining film clips and theatre was researched as a solution for the script writing.

2nd crisis in collaboration - ownership of the scenes

In the project plan, the class had divided into smaller groups to work with scenes. These teams were responsible for at least one scene, writing the manuscript, preparations and directing etc. I tried to stay in the background, to give as much space for the students’ creative work and taking on responsibility. Students were encouraged to offer ideas throughout the process of making scenes and rehearsing so that the piece would evolve according to their choices. While some students were rehearsing acting the others were asked to give feedback and work as directors.

After the first crises and the negotiations the students’ enthusiasm didn’t last long. The students were not happy with improvisation and acting practices. When planning the beginning of the performance, they didn’t come up with any suggestions, so I had to actively construct a proposal. But the students wanted to change the proposal afterwards.

The students continued complaining about the project to the tutors. In the beginning of one art lesson when speaking through the plans some students started to complain and criticize the plan. They criticized that the performance was not theirs, it was made according to the teachers’ ideas. I had to carefully listen to them. I talked with individual students, who seemed to be mostly opposing. In individual discussions with the students, I got an opportunity to listen to them and explain, why we had done, what we had.

According to the teachers’ reflections the problem of the working process was that the students wanted to work individually, but they overestimated their own abilities to work by themselves or take responsibility. In addition, it was difficult for them to know what they wanted when it came to their roles, the planning and the realization of the performance.

The group seemed to come together by resisting the teacher and the teacher had to cope with all the negative energy. With the help of my colleagues I understood that the students’ resistance could be interpreted as a sign of the students being aware of having power that the teacher was listening to them and they were somehow engaged and found the project important for themselves. I had to concentrate better on listening to the experiences, needs and wishes of the individuals of the group. I aimed to have open dialogues and solve the problems together with the group.

I had to critically reflect, if I was acting according to my ideals and goals of activating and empowering the students. Had I fulfilled the promises or expectations I had given the students? I asked myself, if I had really given the students a chance to influence or actively take part in decision-making. The students told me that sometimes I had asked their opinions, but they experienced that I only asked for acceptance for my ideas. I had to learn to be aware of letting the students make suggestions and decisions whenever it was possible or whether they were willing or able to do so. It was not easy for me as an active and creative person. Fortunately, the role of the researcher helped me to step back and behave more as an observer.

The last challenges in collaboration – ownership of the practical arrangements and engagement

Some of the rehearsals of the performance took place during different lessons. The students were strongly critical about having the rehearsals during some of the sports lessons. As this criticism continued we decided with the music teacher to change the schedule so that the students would not miss any of the sports lessons due to the performance.

Even if everybody was asked to have an active role and take responsibility, the students performed differently: some had a stronger sense of responsibility and motivation than others. The students’ orientation in learning situations varied. Some pupils were more interested in creating the performance while others were more interested in communicating and having fun with their classmates. This caused tensions within the group. Students blamed and had difficulties to trust in each other. I as the teacher tried to encourage the whole class to take charge by conducting group reflections, how every student could promote the success of the creation of the performance and what they wished of each other and what they thought they could have done better. This helped for a while, but the group still had some difficulties.

One month before the performance two students expressed that they were not sure if they could come to perform due to their sports hobbies. I was rather fed up with the situation, but some students took responsibility and said that they could manage with the performance without these persons if needed. After changing the schedule and the discussion about everybody’s engagement the atmosphere became better and the students stopped complaining.

However, during the last days before the performance there was still mistrust in the air. Students were suspicious, if the performance would work out at all, as the last rehearsals had not been successful. The students seemed to be tired with rehearsing and the outcome wasn’t looking as good as they had expected. Some test audiences came to watch the performance and other teachers came to give feedback. I as the teacher tried my best to encourage students and promote positive thinking.

Moments before the curtain opened, the students were quite silent and seemed deep in their thoughts. The audience was informed about the principals of devised theatre and that the final performance was created from scratch by the students. The final success of the performance seemed to be a surprise to the students. Every student did their best, the audience was impressed, and the students got good feedback from their audience.

After the performance when watching a film made of their performance, the students seemed to be proud of what they had done and that they had gone through the process. “We got there after all the struggles we had had together”, one of the students said. “Many of us were proud of, at least myself that we could finally show what we had been able to create together from zero. “One of the students wrote. The experiences of working together and learning with each other helped the group to settle down as a more functional and unified group, reflected the teachers involved. “Perhaps the main point has been that we could sing and speak with a common language, “reflected a small group of students.

Conclusions

This article introduced a case study of one devising project with an analysis of the students’ agency based on teacher-researcher’s observation. The results were presented in a diagram of the development of the students’ agency and as a narrative of the collaboration process. The Diagram

1. illustrated the students’ participation process, the turning points of the development of the students’ ownership of performance-making. The teacher-researcher’s narrative described the events of the participation process and reflects on the student/teacher interaction and challenges of teaching.

The case provided an opportunity to evaluate self-study as a method for researching students’ agency. Even if the typifying and assessment of the amount of students’ constructive, resisting or passive agency was estimated and rough, classification of agency revealed the turning points and unfolded the developmental issues of students’ ownership and challenges of engagement. Classification and narrative analyses supported and complemented each other. The observation of agency when evaluating the participation process seemed to be beneficial and worthwhile for improving teaching practice.

This study confirmed the experience of other researchers (i.e. Rainio, 2008; Wessels, 2011, 2012), how the creative processes of drama projects are challenging but offer fruitful episodes for social learning, supporting students’ active agency and development of the ownership. It resembled results of studies of Rainio (2008), when pointing out the importance of seeing students’ resistance as a developmental stage towards engagement and ownership.

The goal of the performance-making project was that the students would take charge of as many aspects of the production as possible. The students’ ownership of the performance developed gradually. The crises were turning points, where the students tested their ownership. They tested, if they could have an influence on the process, in the content of the performance and the working schedule. By resisting and criticizing they challenged the decisions and if their opinions were taken seriously. Later on, the students checked everybody’s engagement in performing.

The case supported the results of other studies (Rainio, 2010), how the development of a student agency and the teacher’s methods were interwoven and interdependent. Collaborative learning necessitated offering the students real opportunities to influence the project and continuous reflective practice throughout the process. The process required from the teacher transformative leadership: motivation and patience for listening to students’ voices and willingness to adjust to the learning process of the students (i.e. Österlind, 2010). Critical reflection (Larrivee, 2000) increased the awareness of the teacher-researcher of the distinction between the ideals, beliefs and values in action.

The collaborative playmaking and devising method provide different spaces for participation and great potential for both the students and the teachers to learn successful collaborative practice. The issue of ownership took place in relation to different levels of drama practice: deciding upon practical arrangements, choices of the themes, methods, creating the text and a structure for the performance, scenography. Drama teacher needs to consider and reflect critically, for which levels participants will hold accountable when preparing the performance.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to all the students and the teachers involved in the playmaking project. I thank the Research Foundation of Mannerheim League for funding my research.

References

Beare, D., & Belliveau, G. (2007). Theatre for positive youth development: A development model for collaborative play-creating. Applied Theatre Researcher Vol. 8.

Borden, R. (2006). Arts education research: A Primer on findings, methodologies, and advocacy. Washington, DC: Arts Education Partnership.

Costley, C., Elliot, G., & Gibbs, P. (2010). Doing work based research. Approach to enquiry for insider- researcher. Los Angeles: Sage. DOI:

Edwards, A. (2005). Relational agency: Learning to be a resourceful practitioner. International Journal of Educational Research, 43, 162-182. DOI:

Edwards, A., & Mackenzie, L. (2008). Identity shifts in informal learning trajectories. In B. van Oers, W. Wardekker, & R. van der Veer (Eds.), The transforming of learning; Advences in cultural historical activity theory. Cambridge University Press. DOI:

Emirbayer, M, & Mische, A. (1998). What is Agency? American Journal of Sociology, 103(4), 962-1023. Gadamer, H.-G. (1976). Philosophical heremeneutics. Berkeley: University of California Press. DOI:

Heddon, D., & Milling, J. (2006). Devising performance: A critical theory. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Heikkinen, H. M. (2005). Draamakasvatus – opetusta, taidetta, tutkimista! In Finnish (Drama education – teaching, art and investigation!). Jyväskylä: Minerva Kustannus.

McManus Holroyd, A. E. (2007). Interpretive Hermeneutic Phenomenology: Clarifying Understanding. Indo-Pacific Journal of Phenomenolog, 7(2), 1-12, https://doi.org/0.1080/20797222.2007.11433946

Jackson, P. W. (1990). Life in classrooms. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Kumpulainen, K., Krokfors, L, Lipponen, L., Tissari, V., Hilppö, J., & Rajala, A. (2010). Learning Bridges: Toward participatory learning environments. Helsinki: CICERO Learning, University of Helsinki.

Lang, L. (2002). “Whose play is it anyhow?” When drama teachers journey into collective creation. Youth Theatre Journal, 16(1), 48-62. DOI:

Lang, L. (2007). Collective in the classroom: Creating theatre in secondary school collaboration projects. Theatre Research in Canada/Recherches théâtrales au Canada, 28(2). DOI:

Larrivee, B. (2000). Transforming teaching practice: becoming critically reflective teacher. Reflective Practice, 1, 293-307. DOI:

Lawler, S. (2002). Narrative in social research. In T. May (Ed.), Qualitative research in action (pp. 242-258). London: Sage.

Lehtonen, A. (2012). Future thinking and learning in improvisation and a collaborative devised theatre project within primary school students. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 45, 104-113. DOI:

Lehtonen, A. (2013). Teaching Participation and Collaboration in a Performance-Creating Project. In R. B. Thorkelsdottir, & Å. H. Ragnars (Eds.), Earth - Air - Water – Fire, with a subtitle humor (pp. 135-163). Reykjavik: FLISS & University of Iceland.

McNeil, L. M. (1986). Contradictions of control: School structure and school knowledge. London: Routledge.

Mills, G. E. (2007). Action research. A Guide for the teacher researcher. 3rd edition. New Jersey, Pearson education.

Muncey, T. (2010). Creating Autoethnographies. Los Angeles: Sage Publications. DOI:

Neelands, J. (2009). Acting together: ensemble as a democratic process in art and life. Research in Drama Education. Journal of Applied Theatre and Performance, 14, 173-189. DOI:

Nelson, B. (2011). Power and Community in Drama. In S. Schonmann (Ed.), Key Concepts in Theatre/Drama Education (pp. 81-86). Rotterdam: Sense Publishers. DOI:

Oddey, A. (1994). Devising theatre. A practical and theoretical handbook. London: Routledge.

Perry, M. (2011). Theatre and knowing: Consider the pedagogical spaces in devised theatre. Youth Theatre Journal, 25(1), 63-74. DOI:

Pinnegar, S., & Hamilton, M. L. (2011). Self-study inquiry practices: Introduction to self-study inquiry practices and scholarly activity. In S. Schonmann (Ed.), Key Concepts in Theatre/Drama Education (pp. 345-350). Rotterdam: Sense Publishers. DOI:

Polkinghorne, D. E. (1995). Narrative configuration in qualitative analysis. International Journal of qualitative Studies in Education, 8, 5-23. DOI:

Rainer, J., & Matthews, M. (2002). Ownership of learning in teacher education. Action in Teacher Education, 24(1), 22-30. DOI:

Rainio, A. P. (2008). From resistance to involvement: Examining agency and control in a playworld activity. Mind, Culture and Activity, 15, 115-140. DOI:

Rainio A. P. (2010). Lionhearts of the playworld. An ethnographic case study of the development of agency in play pedagogy. University of Helsinki, Institute of Behavioral Sciences.

Smith, H., & Dean, R. (2009). Practice-led research, research-led practice in the creative arts, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Swick, M. (1999). Student ownership in the drama classroom. Youth Theatre Journal, 13(1), 72-81. DOI:

Toivanen, T. (2007). Lentoon! Draama ja teatteri koulussa. In Finnish (Fly up! Drama and theatre at school) Helsinki: WSOY.

Toivanen, T., Rantala, H., & Ruismäki, H. (2009). Young primary school teachers as drama educators- possibilities and challenges. In H. Ruismäki, & I. Ruokonen. (Eds.), Arts contact points between Cultures. 1st International Journal of Intercultural Arts Education Conference, Post-Conferense Book (pp. 129- 140). University of Helsinki: Research report 312.

Toivanen, T., Komulainen, K., & Ruismäki, H. (2011). Drama education and improvisation as a resource of teacher student’s creativity. Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences 12, 60-69. DOI:

Toivanen, T., Pyykkö, A., & Ruismäki, H. (2011). Challenge of the empty space. Group factors as a part of drama education. Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences, 29, 402-411. DOI:

Vygotski, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Webster, L., & Mertova, P. (2007). Using narrative inquiry as a research method, an introduction to using critical event narrative analysis in research on learning and teaching. London: Routledge. DOI:

Wessels, A. (2011). Devising as pedagogy. In S. Schonmann (Ed.), Key Concepts in Theatre/Drama Education (pp. 59-63). Rotterdam: Sense Publishers. DOI:

Wessels, A. (2012). Plague and paideia: sabotage in devising thetare with young people. Research in Drama Education, Journal of Applied Theatre and Performance, 17, 53-72. DOI:

Wright, P. (2011). Agency, intersubjectivity and drama education: The power to be and do more. In S. Schonmann, (Ed.), Key Concepts in Theatre/Drama Education (pp. 111-115). Rotterdam: Sense Publishers. DOI:

Österlind, E. (2010). Drama måste byggas I vardagen- dramalärares ledarskap. In A.-L. Østern, M. Björkgren, & B. Snickars-von Wright (Eds.), Drama in three movements: A Ulyssean encounter (pp. 81-86). Vaasa: Åbo Akademi, Faculty of Education. Report Nr 29/2010.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.