The Enabling Constraints of Building an Assessment Pedagogy: Engaging Pre-service Teachers in a Professional Exploration of Current Conceptions of Classroom Assessment

Abstract

Teachers’ assessment practices can influence students’ learning by supporting instruction and, more importantly, by developing students’ self-monitoring skills and regulation of their learning. Contemporary notions of classroom assessment have moved beyond the traditional concepts of formative and summative assessment. These contemporary approaches require teachers to reconceptualize their orientation towards teaching and learning. Pre-service teachers believe they require a teaching and assessment toolbox in order to be successful. Hence, they struggle to move beyond simplistic notions of learning and assessment. Our research examines how the concepts of “Enabling Constraints” and “Wicked Problems” guide our own teaching and research while also developing pre-service teachers’ own conceptions of professional learning within the context of current conceptions of classroom assessment. Surveys, discussions, and assessments of approximately 700 pre-service teachers’ thinking and reflections about classroom assessment collected as part of in-class assessment activities provide the research data. Descriptive and thematic analyses highlight our challenges and successes as we work to meet the learning needs of pre-service teachers, while also creating a context for ongoing professional learning that helps pre-service teachers move beyond a simplistic, primarily instrumental orientation towards teaching and classroom assessment. The operational constraints of the B.Ed program have required us to carefully examine how best accomplish these goals. The introduction of “Wicked problems” has helped to highlight the complex relationships between teaching and assessment and the need to develop an assessment pedagogy that integrates assessment practices and theories.

Keywords: Teachers’ assessment, pedagogy, classroom assessment

Introduction

Current educational climates place a heavy emphasis on educational accountability, with expectations that educational reform and improvement will be guided by the use of sound data and information in the hands of professional educators (e.g., Elmore, 2004; Popham, 2002). Such data-informed decision-making is considered a powerful way to direct school improvement efforts (e.g., Creighton, 2007; Earl & Katz, 2006). These accountability models and improvement efforts typically use student achievement results from large-scale assessment results as the primary source of data and information, under the assumption that such measures provide educators with objective and consistent measures of education quality. Yet it remains unclear the extent to which such data sources can provide the necessary information to either guide improvement efforts or measure subsequent changes, or the ability of educators to use these data sources effectively (e.g., Klinger, Maggi, & D’Angiulli, 2011; Klinger & Rogers, 2011; Shulha & Wilson, 2009). While the relationships between large-scale assessment, accountability and student achievement have been critically examined, the potential of classroom assessment information to support educational improvement efforts has received far less attention.

Nonetheless, there is growing evidence that the data gained from classroom assessments, and classroom assessment practices themselves, can have a strong impact on teaching and learning (e.g., Black & Wiliam, 1998, 2003; Brookhart, 1999; Earl, 2003; Hume & Coll, 2009).

Teachers constantly assess their students’ knowledge and skills, both to report on student achievement and to inform subsequent instructional decisions. Further, teachers’ assessment practices have the potential to influence students’ learning, and perhaps more importantly, students’ self-monitoring and regulation of their learning (e.g., Black & Wiliam, 1998, 2003; Earl, 2003; Hargreaves, Earl, & Schmidt, 2002; Hume & Coll, 2009; Natriello, 1987). Previous concepts of formative and summative assessment certainly recognized the value of teachers’ assessment practices and data to inform teaching; however, more recent research suggests that these classroom assessments may also have a more direct influence on students’ learning and their own educational pursuits. These contemporary notions of classroom assessment are now commonly summarized as “Assessment OF Learning” (AOL), “Assessment for Learning” (AFL), and less commonly “Assessment AS Learning” (AAL) (e.g., Black & Wiliam, 1998; 2003; Earl, 2003). These notions of assessment align with motivational research that links mastery approaches to learning and internal motivation to higher levels of student achievement (Biggs, 1995; Pintrich & Schunk, 2002). These contemporary approaches to assessment require teachers to reconceptualize not only their philosophies regarding the roles and purposes of assessment, but also their assessment practices to have a greater focus on student learning.

Central to this shift, teachers need to learn to engage students more fully in the assessment process, allowing students to begin to use assessment feedback and information to direct their own learning.

Teachers generally feel comfortable using assessment information to support their own lesson planning and instruction, however, there is far less evidence that teachers are able to help students use assessment information to support their learning (Ecclestone, 2007; Marshall & Drummond, 2006). Unfortunately, introducing teachers to these new conceptions of classroom assessment is not easy, and teachers are ill-prepared to explore assessment theories and practices in deep and meaningful ways. As an example, the large majority of teacher preparation programs in Canada do not require specific training in classroom assessment (DeLuca & McEwen, 2007). And the problem is not limited to Canada. Stiggins (2004) noted that in the United States, less than 20 states require demonstrated assessment competency as a prerequisite for teacher licensure. The challenges continue into the profession itself. Practicing teachers rarely have the opportunity to more deeply explore their own assessment practices, share current understandings, or develop their expertise in the use of assessment information. And when they do, they are often not able to fully understand the complexity underlying contemporary assessment practices and philosophies (Ecclestone, 2007; Marshall & Drummond, 2006). Nonetheless, Ministries of Education across Canada are increasingly incorporating assessment “Of,” “For,” and “As” learning concepts into their policy documents with the expectation that teachers will implement these philosophies and practices.

Purpose of the Study

Given the increasing focus on assessment in Canadian education and the importance of assessment on students’ learning, our research focuses on our attempts to help pre-service teachers better understand the current conceptualizations of classroom assessment. Specifically, our research examines the ongoing efforts to create a professional learning context where pre- service teachers are motivated to go beyond a simplistic, primarily instrumental orientation toward assessment and recognize the influence of their assessment decisions on teaching and learning.

Teacher Education in Ontario

Education in Ontario, Canada’s most populated province, falls under the jurisdiction of the provincial government. The Ministry of Education is responsible for K-12 educational policy, including subject curriculum and grading policies. Distinct from the Ministry of Education, The Ontario College of Teachers (OCT) is a regulatory body for teachers in the province. It is an independent body that provides a mechanism for the teacher profession to regulate and govern itself. Teachers in publicly funded schools must be certified by the College to teach in Ontario and they must be members of the college. OCT also publishes the Foundations for Professional Practice (Ontario College of Teachers, 2010), outlining “the principles of ethical behaviour, professional practice and ongoing learning for the teaching profession in Ontario” (p. 3).

With the increasing focus on assessment in Ontario schools, teacher education programs are encouraged by the OCT to address assessment in their Bachelor of Education programs. As the accrediting and governing body for teaching in Ontario, the OCT also mandates standards of practice and guidelines for pre-service programming, although it does not control the teacher education programs themselves. For program accreditation, Faculties of Education must meet the standards reflected and promoted by the College’s Foundations for Professional Practice. In particular, teachers and pre-service teachers are expected to “use appropriate pedagogy, assessment and evaluation, resources and technology in planning for and responding to the needs of individual students and learning communities” (Ontario College of Teachers, 2010, p. 13).

The emphasis on teacher competency in classroom assessment practices and the role of assessment in student learning is also recognized in a recent policy document by the Ontario Ministry of Education (2010) entitled.

Since Faculties of Education across the province have direct control of the undergraduate and graduate programs they offer, they are also relatively free to determine the manner in which they prepare new teachers to meet the OCT standards. Nonetheless, since tuition fees provide less than 30% of the operating costs, Bachelor of Education (B. Ed) programs are constrained by the provincial funding provided to the universities to support teaching. Given these constraints, the majority of Ontario’s B. Ed programs are eight-months in length, with students entering the program after the completion of an undergraduate degree in another faculty. Hence the general requirement to become a teacher is the completion of five years of university, resulting in two undergraduate degrees completed “consecutively.” Alternately, students graduating from high- school can choose to directly pursue a degree in education. These “concurrent” pre-service teachers simultaneously complete an undergraduate degree from another undergraduate field of study, while also taking education courses in their first four years. In their final fifth year, they complete a similar eight-month program as the post-degree (consecutive) pre-service teachers.

These operating constraints have resulted in each Faculty of Education creating its own somewhat unique Bachelor of Education program, intended to meet the expectations of the OCT given the logistic constraints and available faculty.

Of specific interest to our research are the models used to approach teacher preparation in classroom assessment and evaluation. There appear to be four models that are being used: (a) required assessment courses, (b) required professional studies or curriculum courses that integrate assessment, (c) elective assessment courses, and (d) elective educational courses that integrate assessment (DeLuca & McEwen, 2007). Currently, only 3 of the 10 Education programs in Ontario offer a required assessment course, and it is not known the extent to which other required courses address classroom assessment issues, practices and philosophies. While assessment skills are considered an important standard for professional practice by the OCT and the profession itself, it is not at all clear the extent to which graduating teachers in Ontario are able to meet this standard.

The Classroom Assessment Module at Queen’s University

Our research is based on work with pre-service teachers in our Bachelor of Education program at Queen’s university in Kingston, Ontario. Based on recommendations from a previous accreditation in 2006, and the comments of previous pre-service teachers in the B.Ed program, we developed a mandatory Classroom Assessment Module (CAM) that all B.Ed pre-service teachers complete in their final year. The module is taught in a large lecture hall to two different groups with approximately 350 pre-service teachers each. Separate lectures are provided to elementary and secondary teacher candidates. Each lecture is one hour in length and the number of classes per year has varied from 7 to 9. As with the B.Ed programs across the province, the structure of the module does not provide an ideal mechanism to support pre-service teachers’ assessment learning needs.

Given the constraints of the module structure, we have been working to find ways to maximize the value of the assessment module to our pre-service teachers. The module is now in its fifth year. As the professors of this module over this time period, we have continually evaluated the impact of the module on pre-service teachers’ conceptions of classroom assessment and professional learning. As part of our ongoing reviews and formal evaluations of the CAM, we have worked with our graduate students to gather an understanding of pre-service teachers’ learning and their perceptions of the structure and utility of the module. The information gleaned from focus groups, interviews, surveys, and course feedback have been used to continually refine the module itself and the manner in which we work with these undergraduate pre-service teachers. As an example, the creation of the assessment lab was a direct result of feedback from pre-service teachers regarding the need for opportunities to sit down and talk about assessment issues and practices. Further, our previous interactions with pre-service teachers have highlighted the need to continually promote the notions of assessment “for” learning.

Despite these efforts to enrich the quality of information and interactions experienced by our teacher candidates, we remained troubled by the number of pre-service teachers each year who express indifference to learning about formative assessment and seem to be resistant to using assessment tools intended to track their own growth or the growth of their students. Yearly modifications to our own assessment tools have included various versions of formative online quizzes, assessment portfolios, and a self-developed “assessment report card.” It should be noted that grading in this module is on a pass/fail dichotomous scale. This allows us a significant freedom in establishing the criteria for success within the module.

Our Previous Research and Findings

Our efforts to better understand and address B. Ed pre-service teachers’ needs continued during the 2009/2010 academic year, we began the year with an in-class questionnaire that was completed by 596 (85%) pre-service teachers. The questionnaire focused on their perceptions of the methods and resources that best helped them to learn. Second, and in recognition of the need to address more specific issues in classroom assessment, we, along with our graduate students, offered a series of voluntary lunch-time “Brown Bag Blitzes.” These seminars occurred during the second term and after the completion of the CAM. The Brown bag blitzes were extremely well attended and we used the opportunity to gain further insights into these soon to be graduating, B.Ed pre-service teachers’ perceptions of the CAM and our efforts to help them better understand the associations between classroom assessment and learning. The subsequent survey was completed by 286 (41%) of the teacher candidates.

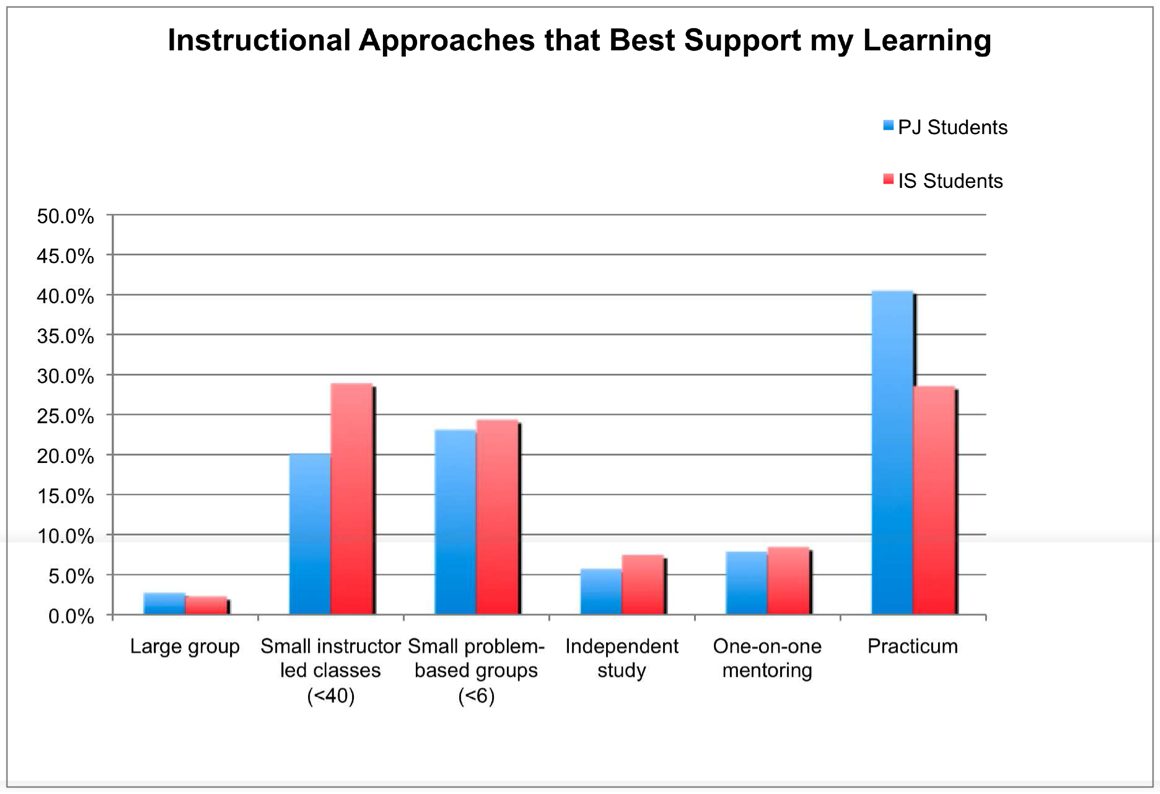

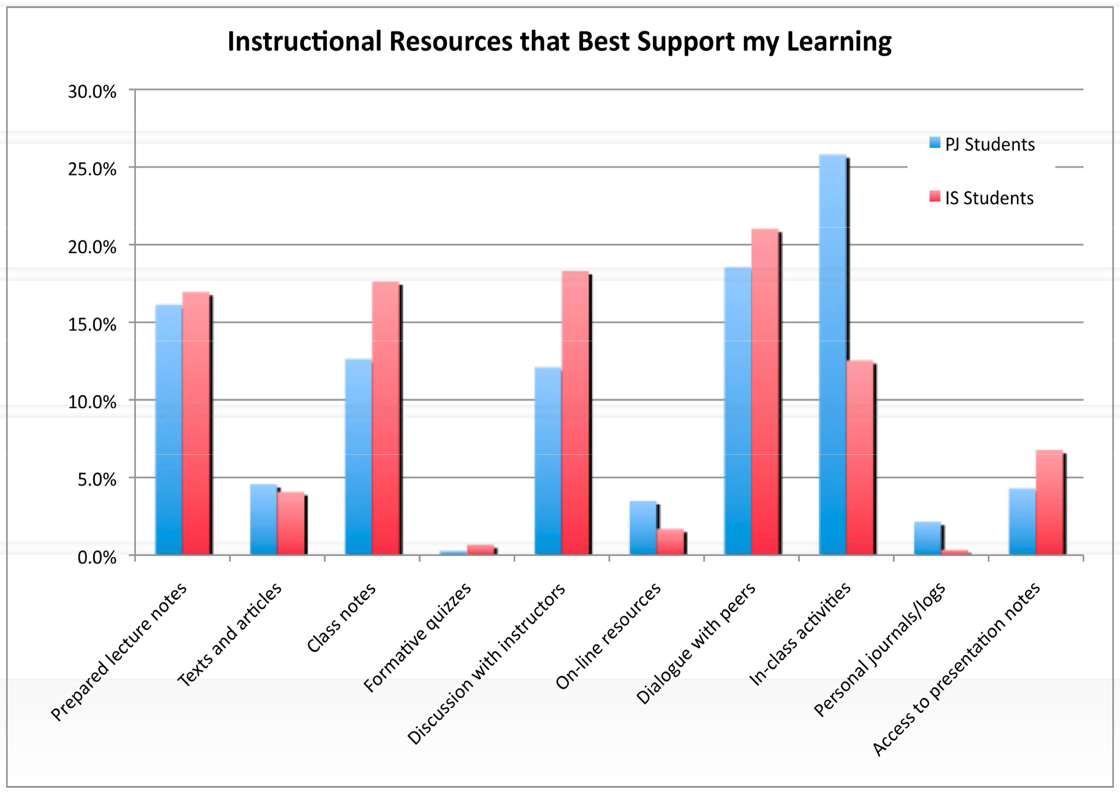

Pre-service teachers’ responses to the questionnaire given at the beginning of the school year are summarized in Figures 1 and 2. Both the elementary (PJ) and the secondary (IS) B.Ed pre-service teachers were relatively similar in their responses, with some notable exceptions. PJ pre-service teachers believed the practicum was of much greater value while IS pre-service teachers valued the smaller instructor led classes. Neither group valued the large group format, the format used in the CAM, nor did candidates value independent learning or one on one mentoring. While we were not surprised by the overall dislike for the large group lectures, the lack of support for independent study and mentoring was more interesting. Independent study is one heavily promoted aspect of professional learning while one on one mentoring is a model being increasingly used to support first year teachers in Ontario. PJ candidates strongly supported the use of in class activities and dialogues with peers. IS candidates valued dialogues with peers, and their instructors, and also class notes. Neither group valued personal journals, logs, formative quizzes or online resources, key components of the CAM and in the case of formative quizzes and journals, an important foundation of AFL and self-regulated learning we were intending to promote.

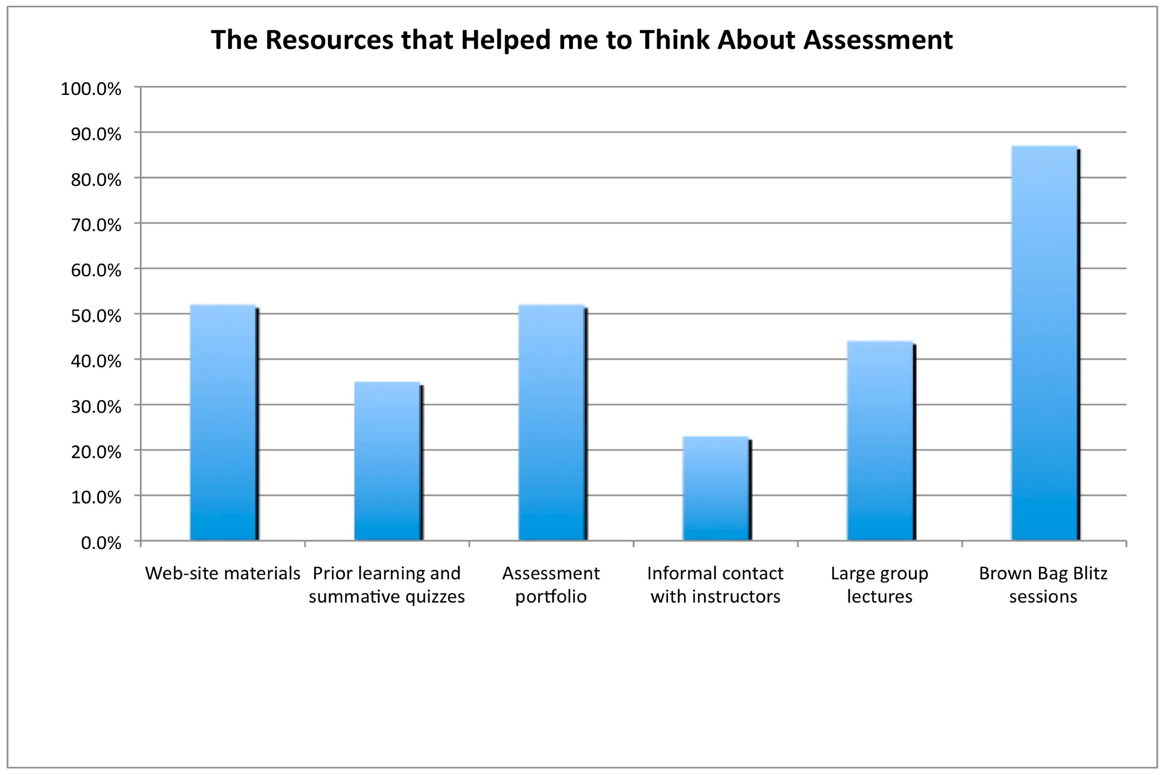

The results obtained in the survey completed by pre-service teachers who attended the “Brown Bag Blitzes” are presented in Figure 3. We were unable to separate these results by program (elementary and secondary). Informal contact with the instructors was the least helpful, not a surprising finding given that the auditorium format limited this opportunity. As the primary instructors we did make ourselves available to candidates 30 minute prior to and after each class, but class schedules may have made it difficult for candidates to contact us during these times.

There was mixed support for the other aspects of the module. Of particular interest to us was the extremely large support for the “Brown Bag Blitzes.” These seminars proved to be very popular with teacher candidates. Candidates written comments echoed our findings. There was also a real dichotomy in candidates’ responses with some being extremely supportive of an aspect of the CAM while other reporting that the same aspect was not at all helpful. As an example, one candidate commented “The learning portfolio was not very useful to me as a learner. I saw it as one more thing I had to do.” In contrast, a second wrote “I enjoyed the assessment portfolio. In the beginning I didn’t want to do it, but I found it useful in developing my ideas personally and with the help of a peer, I enjoyed the academic and valuable conversations and thoughts it provoked.” In other examples, pre-service teachers wrote of insufficient or excessive theory, or of now feeling more confident or not confident at all.

Certainly, the most pervasive finding was the challenge of using the auditorium in a lecture format. B.Ed pre-service teachers were generally very supportive of our efforts, but their comments reflected a lack of connection with the conceptions of professional learning and AFL that we intended to nurture in these candidates. Our evidence suggests the format of the module prevented deep discussions and meaningful explorations of professional learning and assessment concepts and issues, resulting in only a surface understanding of the complexities teaching and classroom assessment. We could not find extensive evidence that the majority of pre-service teachers fully understood the underlying assessment philosophy we were promoting in the module nor the connection to self-directed professional learning they would soon be expected to embrace as practicing teachers.

Our Current research

The ongoing constraints identified above have resulted in further changes to the manner in which we approach the CAM. The structure of the CAM was modified in 2010/2011 to occur only once per week and to extend across the second teaching practicum. Previously, the entire module was taught in three weeks. The extended timeline bridging a teaching practicum was intended to enable pre-service teachers to more deeply explore assessment issues and practices more deeply and in the context of teaching. The large group format remained and this certainly prevented us from fully engaging candidates with the concepts being explored. Nonetheless, the large group lectures have served to expose more fundamental challenges to working with pre- service teachers. We have identified three major challenges to address for the 2010/2011 academic year: 1) the challenge to help these soon to be teachers transition from the role of student to practicing teacher; 2) the need to model and promote the concepts and expectations of professional learning; and 3) that while, as a group, pre-service teachers ask important and complex questions, their focus remains on acquiring narrow and largely instrumental understandings of classroom assessment even when opportunities to examine complexity are available and supported.

The current revision to the CAM has involved two shifts in our approach: to the module itself, and to the way we work with our pre-service teachers. The first shift has resulted in changes to the instructional perspectives and assessment methods we use in the module. From an instructional perspective, we have reconceptualised the focus on classroom assessment to be one of “assessment pedagogy,” in which all forms of assessment must be closely aligned and considered along with other aspects of teaching and learning. We promote assessment not as distinct from but rather as integrated with curriculum planning and instruction. We have advocated AFL to be more about an assessment philosophy rather than the use of specific forms of assessment instruments or procedures. To this end, we have made purposeful design decisions intended to model how teaching and learning might unfold when the goals of AFL are at the heart of pedagogy.

We have also endeavoured to help pre-service teachers better understand the complexities of teaching and learning and the role of assessment in this process. This has enabled us to promote classroom assessment in the CAM as a “Wicked Problem” (Conklin, 2006; Rittel & Webber, 1973). Wicked problems are those in which solutions become more difficult to clearly identify as more is known about the problem itself. The underlying complexity of social science problems commonly faced by teachers make the identification of a standard solution more difficult to find.

Through the concept of “Assessment as a Wicked Problem,” our approach to the module has been to introduce assessment concepts first from the simplistic instrumental assessment questions and concerns of pre-service teachers. From here, we then illustrate and explore the increasing complex assessment related questions and issues that arise as teachers develop a more complete understanding of teaching and students’ learning needs. The solutions to these assessment related issues are then described to be a function of teachers’ assessment philosophy rather than through a set of assessment techniques or practices.

From a professional learning perspective, we have modified the CAM expectations for pre-service teachers. Professional learning is promoted as being more self-directed and requiring the identification of short-, medium-, and long-term learning goals. Hence, in the latest offering of the CAM, pre-service teachers were required to develop a professional learning plan that included short-, medium-, and long-term goals and actions (see Appendix A), as well as an exemplar to guide them through the process (See Appendix B). There is an expectation for careful self-reflection and the identification of potential learning resources to guide subsequent learning. The initial plan is completed prior to the second practicum and handed in three weeks after the return to classes. Feedback is provided with respect to the short-term goal that occurred during the recently completed practicum, and guidance for subsequent learning. Throughout, the learning plan is described as a self-regulated method for each pre-service teacher to guide and direct their own teaching.

Changing the Way We Work with Pre-service Teachers

Our second shift was to modify the way we work with pre-service teachers. Based on the shifts in our perspectives and assessment strategies described above, our challenge became: How do we support deep learning about wicked problems in assessment? Three approaches were implemented: direct instruction in self-regulated learning; continued enrichment of the learning resources, and close attention to modeling the philosophy underlying assessment for learning.

Direct instruction in self-regulated learning.

Before introducing concepts of assessment, we spent time engaging in experiences and discussions to help our pre-service teachers explore the transition from ‘student’ to ‘professional teacher’ and the implications this has on how their learning occurs. We then walked through the stages of self-regulated learning: monitoring one’s activities, self-evaluation of one’s performance and decision-making based on performance outcomes (Zimmerman, 2002). This work concluded with the exploration of a rubric intended for their use in any context during their pre-service year (see Appendix C).

Continued enrichment of the learning resources.

With the help of graduate students we continued to refine the modules designed to introduce candidates to the concepts of What Learning Looks Like, AFL, AAL and AOL. These included new materials, readings, and links to online lectures and presentations (e.g., TED talks, ITunesU). In addition, we created an introductory module to help candidates think about the role of assessment in a learning culture (Shepherd, 2000) and the role of assessment in the provincial School Effectiveness Framework (Literacy and Numeracy Secretariat, 2010).

Modeling the philosophy and theory of assessment for learning

Through our instruction and questions and demonstrations we worked to promote the underpinnings of AFL. Partway through the module, we presented the ITunesU video entitled Assessment Strategies (Wiliam, ITunes U, downloaded February 2011). In this video, Wiliam posits five key elements to Assessment for Learning: (a) knowing where the learner is, (b) clarifying the success criteria, (c) giving feedback to move the learner forward, (d) peers supporting each other, (e) engaging in self-assessment. Our intention was to highlight how these elements would work in practice through the module itself.

In a class of 350 it is difficult to pinpoint the thinking of individuals. One option is to obtain a sense of the variability of thinking within the group. Each of our 7 classes on assessment began with the posing of a wicked problem concerning classroom assessment. After reading the scenario students were asked to use clickers to select either a key element in the scenario or a strategy a teacher might use in responding to the dilemma. Results were posted immediately for the entire group to observe the results. The responses invariably led to lively discussions about which answer was correct and why. One important observation we made during these activities was how important it became for some pre-service teachers to argue for the “correctness” of their response even though our emphasis was to demonstrate how the ‘best’ response would differ depending on the context and values in play within the scenario.

When we introduced our pre-service teachers to the requirements of the module, i.e., creating and enacting at least a short-term goal in assessment, we worked to help them understand what such a plan might look like. This was accomplished primarily through the use of an examplar that described the success criteria (See Appendix B). While we emphasized that this did not have to represent the structure for communicating their learning plan, only one student chose not to use the structure.

Not surprisingly, the work to provide feedback to 700 pre-service teachers on their learning plans was resource intensive. Six graduate students worked for two weeks to complete the feedback. The process began with two graduate students and us reading over a sample of responses, discussing the strengths and limitations of the submissions., and eventually developing an analytic rubric that specified the qualities of each planning element at three different levels of expertise. This rubric was then tested and refined by the graduate students as they assessed the next 50 submissions. Using this process, we were able to provide each candidate with feedback on the qualities we saw in their product.

The day we returned the learning plans to the pre-service teachers we introduced the rubric and how it would next be used for peer assessment. The formal instructions were as follows:

Instructions for All Pre-service Teachers:

Review the Rubric

- Review the descriptions of how each of the element changes in quality (Read across a row).

- With your peer, discuss each row until you are confident that you can tell the difference between the elements and the levels.

- Add any ideas you have to any cell if this helps you see these differences better

Instructions for Peers:

- Read over (observe) your partner’s responses to the 5 elements that describe her/his Learning Plan for the short-term goal only.

- Ask any questions you have about how these are written.One element at a time, compare what you have read with the descriptions provided on the rubric for the quality indicators, Beginning, Developing or Advancing.

- Indicate to your peer the quality of each element in her/his plan.

Through this activity, the pre-service teachers had two pieces of formative feedback on their learning plan, one from us and one from a peer. Finally, we asked them to reflect on their learning and identify next steps. Our concern at this stage was how these pre-service teachers could use the feedback to help guide their decisions for next steps. Our solution was a scaffolding rubric (See Appendix D). As the pre-service teachers situated their performance on the rubric, they could then find suggestions on how they might proceed to the next level of performance.

Our Own Learning

The operating constraints of the classroom assessment module have required us to continually evaluate our efforts and explore alternative options and mechanisms to support pre-service teachers learning about assessment. Nevertheless, these constraints have encouraged us to continue to build our own knowledge base as we search for other approaches and knowledge to use in our teaching. Rather than settling into comfort and certainty, we have continued to be creatively challenged. We have come to understand that the limitations of the CAM have actually created “enabling constraints” (Davis, Sumara, & Luce-Kapler, 2008) that focus our attention on the complexity of our teaching situation and encourage the exploration of creative possibilities. “Enabling constraints,” as a concept from complexity theory, does not describe situations that demand prescriptive, predetermined answers but rather explains complex contexts where the limitations fuel expansive responses. “Enabling constraints” also illustrate the complexity of teaching and learning and the need to incorporate much more than the accumulation of information to understand the implications of our efforts. Rather, our current understandings of the CAM and pre-service teachers’ assessment needs have been the result of a complex process that has incorporated a diversity of our experiences. While this mindset of “enabling constraints” has greatly enriched our professional learning, it is one we also hope to develop in our teacher candidates who will daily face such complexity in their own classrooms.

Our ongoing work with pre-service teachers has identified the real need to create a supportive learning culture, and the time it takes for this culture to develop. Pre-service teachers continue to have difficulties transitioning from student to practicing teacher. Given this, it is not surprising that many are subsumed with concerns about learning expectations and assignments. Professional learning may still be a distant concept for them and for many it appears they may have heard the words but did not fully understand the message. Admittedly, these are not universal findings, and each iteration of the CAM appears to have an increasing proportion of pre-service teachers who acknowledge the value of the CAM and what they themselves have learned as a result of their own self-directed learning efforts.

Certainly, our efforts to promote professional and self-regulated learning appear to have potential. At the same time, the notions of “assessment pedagogy” and “assessment as a wicked problem” seem to resonate with many pre-service teachers. The quality of pre-service teachers’ questions, and examples of their learning illustrate increasingly deeper understandings. We have identified a more integrated, longer-term approach to professional learning and an acknowledgement of the complexity of teaching, learning and assessment. Admittedly, we do require more empirical evidence with respect to the impact of our efforts and changes. Until now, our work has been its own example of self-regulated professional learning, as we have endeavoured to better understand the critical aspects of our teaching and work with pre-service teachers. Our own discussions have resulted not only in shifts to the ways in which we approach our teaching of the CAM, but also in our own thinking about the integration of assessment, teaching and learning. We believe our efforts are resulting in important shifts in the way we approach teacher education. Of course, one of the key limitations continues to be the largely anecdotal evidence of the impact of our efforts. Such evidence has been important but it is incomplete. Hence our subsequent work will continue to build on our experiences while also obtaining other empirical evidence from the pre-service teachers with respect to their changing conceptions of assessment pedagogy and self-regulated professional learning.

Acknowledgements

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

Biggs, J. B. (1995). Assessing for learning: Some dimensions underlying new approaches to educational assessment. Alberta Journal of Educational Research, 41(1), 1-8.

Black, P. J., & Wiliam, D. (2003). In praise of educational research: Formative assessment. British Educational Research Journal, 29(5), 623–637.

Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (1998). Inside the black box: Raising standards through classroom assessment. Phi Delta Kappan, 80(2), 139-148.

Brookhart, S. M. (1999). Teaching about communicating assessment results and grading. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 18(1), 5-14.

Conklin, J. (2006). Dialogue mapping: Building shared understanding of wicked problems. West Sussex, England: John Wiley & Sons,

Creighton, T. (2007). Schools and data: The educator’s guide for using data to improve decision making (2nd Ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Davis, B., Sumara, D., & Luce-Kapler, R. (2008). Engaging minds: Changing teaching in complex times (2nd Ed.). New York: Routledge.

DeLuca, C., & McEwen, L. (2007, April). Evaluating assessment curriculum in teacher education programs: An evaluation process paper. Paper presented at the annual Edward F. Kelly Evaluation Conference, Ottawa, ON.

Earl, L. (2003). Assessment as learning: Using classroom assessment to maximise student learning. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Earl, L., & Katz, S. (2006). Leading in a Data Rich World: Harnessing Data for School Improvement. Thousand Oaks: Corwin Press.

Ecclestone, K. (2007). Commitment, compliance and comfort zones: The effects of formative assessment on vocational education students’ careers. Assessment in Education, 14(3), 315-33.

Elmore, R. F. (2004) School Reform from the Inside Out: Policy, Practice, and Performance. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard Education Press.

Hargreaves, A., Earl, L, & Schmidt, M. (2002). Perspectives on alternative assessment reform. American Educational Research Journal, 39(1), 69–95.

Hume, A., & Coll, R. K. (2009). Assessment of learning, for learning and as learning: New Zealand case studies. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy, and Practice, 16, 269-290.

Klinger, D. A., & Rogers, W. T. (2011). Teachers’ perceptions of large-scale assessment programs within low-stakes accountability frameworks. International Journal of Testing, 11, 122-143.

Klinger, D. A., Maggi, S., & D’Angiulli A. (2011). School accountability and assessment: Should we put the roof up first. The Educational Forum, 75(2), 114-128.

Literacy and Numeracy Secretariat. (2010). The K-12 School Effectiveness Framework: A support for school improvement and student success. Government of Ontario.

Marshall, B., & Drummond, M. J. (2006). How teachers engage with assessment for learning: Lessons from the classroom. Research Papers in Education, 21(2), 113-149.

Natriello, G. (1987) The impact of evaluation processes on students. Educational Psychologist, 22(2), 155–175.

Ontario College of Teachers. (2010). Foundations of professional practice. Toronto: ON. www.oct.ca/publications/PDF/foundation_e.pdf

Ontario Ministry of Education. (2010). Growing Success: Assessment, Evaluation, and Reporting – Improving Student Learning. Toronto: ON. Queen’s Printer.

Pintrich, P. R., & Schunk, D. H. (2002). Motivation in education: Theory, research, and applications (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill.

Popham, W. J. (April, 2002). High-stakes tests: Harmful, permanent, fixable. Paper presented at the Annual Conference of the American Research Council, New Orleans, LO.

Rittel, H. W. J., & Webber, M. M. (1973). Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sciences, 4, 155-169.

Shepherd, L. A. (2000). The role of assessment in a learning culture. Educational Researcher 29(7), 4-14.

Shulha, L. M., & Wilson, R. J. (2009). Rethinking large-scale assessment. Assessment Matters 1, 111-133.

Stiggins, R. (2004). New assessment beliefs for a new school mission. Phi Delta Kappan, 86, 22-27.

Wiliam, D. Assessment Strategies. Learning and Teaching Scotland. ITune U.

Zimmerman, B. J. (2002). Becoming a self-regulated learner: an overview. Theory into Practice 41(2), 64-70.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.