Abstract

The current study has been performed in order to compare social physique anxiety and Body Dismorphic Disorder between a group under medical cosmetic treatments and a control group. The study population consisted of 200 subjects, undergoing medical cosmetic therapy and 200 not receiving any medication considering this matter, which were selected by hand-to-hand and simple random sampling. In this post-causal study, to gather the information required for Heart’s social physical anxiety criterion, Philips’ Body Dysmorphic Disorder diagnostic questionnaire was distributed amongst the subjects. A significant difference and opposition, considering the degree of social physical anxiety (p=0.04), the number of persons with Body Dysmorphic Disorder (P=0.05) and those who showed a tendency towards cosmetic surgery (P=01), was observed between the main group of subjects and the control group. In both groups, those who had physical disorders, abnormalities or deformities, experienced higher levels of social physique anxiety. This value was reported higher in the subjects of the control group. The results indicate that the subjects of the group which had visited a center in order to receive cosmetic treatments, experience lower levels of social physique anxiety. Having Body dysmorphic Disorder and not receiving the required cosmetic treatments and medications, were determined the most important factors in predicting social physical anxiety levels, whilst other attributes, such as gender and the patient’s tendency towards undergoing a cosmetic surgery, are not effective in the prediction of such a value.

Keywords: Body Dismorphic disorder, social physique anxiety, under cosmetic treatment

Introduction

Having a realistic and appropriate mental image is necessary for a healthy and satisfactory lifestyle and adaptation to the environment. If the person has a good feeling about her/his body, s/he would have a greater chance of achieving a positive body image. Sometimes, stress and anxiety, self-criticism perspectives or a low level of self-esteem in relation to a person’s body can cause some people to change their appearance and body, and try beauty and treatment and cosmetic surgery (Stuart & Grimes, 2009). Social physique anxiety is a type of anxiety, which is very important due to interaction between the body and the community. According to Hart et al. (1989), social physique anxiety is the result in response to others’ assessment of their physiques. A person with this type of anxiety avoids any situation in which s/he will be physically evaluated, and has the feelings of distress and concerns regarding negative evaluation of others (Brown, 2000; Pernick et al., 2006; Weinberg & Gould, 2011; Cox, Ullrich-French, Madonia, & Witty, 2011). People who have high levels of social physique anxiety will experience more stress during fitness tests and in fitness settings, and are less inclined to participate in physical activities. Eating disorders and low self-esteem are greatly associated with this type of anxiety (Davison, & McCabe, 2005; Kruisselbrink, Dodge, Swanburg, & MacLeod, 2004). Women are more likely than men to show higher levels of social physique anxiety and its effects (Davison, & McCabe, 2005; Fitzsimmons-Craft, 2012). Recently, this process has increased in men as well (APA, 2000; Reese, McNally, & Wilhelm, 2011; Lim, 2013). People with social physique anxiety manage their stress and anxiety in different ways (Phillips, 2005). Researchers found that some women use stress-coping strategies, such as behavioural avoidance, short-term strategies of appearance, management, social support, cognitive avoidance and acceptance, for the management of their social physique anxiety. Many of these strategies have short-term impacts, while in the long-term they may lead to worsened and chronic anxiety (Mancuso, Knoesen, & Castle, 2010; Phillips, 2009).

Body dysmorphic disorder is a mental preoccupation with a slight defect in appearance or, in case of presence of minor physical anomaly, the patient's anxiety is extreme and excruciating (Phillips, Dufresne, Wilkel, & Vittorio, 2000). The patients often attempt to perform ceremonial behaviours such as excessive cleaning, checking themselves in the mirror, excessive use of make-up or camouflaging of their appearance with clothing or jewellery. This disorder causes social, educational and occupational performance degradation (Samari & Lalifaz, 2005). In the fifth edition of the Diagnostic Statistical Mental Disorders (DSM-V), doing repetitive behaviours such as checking in the mirror, over-checking the skin and comparing appearance with others, the muscle deformity has been added as a diagnostic criterion to the other criteria outlined in the DSM-IV-TR. In this edition, the insight level of patients with BDD has been considered (Anson, Veale, & de Silva, 2012). The organs of main concern in this disorder include the skin, hair and nose; however, the disorder is not limited to these organs only and involves concerns, such as the appearance as well as other physical traits, including abnormal walking, breakouts, going bald, etc. Patients with this disorder spend on average three to eight hours, and a quarter of them more than eight hours, a day thinking about their appearance defects (Anson, Veale, & de Silva, 2012). Many of these people have no insight regarding their concern or have a low level insight (Veale et al., 1996; Sarwer & Spitzer, 2012), and think that others are paying special attention to their appearance defects (Talaei et al., 2006). Body dysmorphic disorder usually begins during early adolescence; however, it may occur in children or in adults as well. Studies have shown that women mostly experience the mild form of the disorder, while men will experience the more severe form of the impairment (27). The prevalence of this disorder may appear equally in outpatient mental health centres in men and women (Phillips, Dufresne, Wilkel, & Vittorio, 2000).

Epidemiologic studies have shown the following statistics about the prevalence of this disorder (Russell, 2002), 2.2-13% of students, 13-16% of psychiatric patients in hospitals, 14-42% of outpatient patients with major depression, 39% of patients with mental anorexia, 9-14% of patients eager to undergo treatment via skin surgery and 3% to a half of patients keen on cosmetic surgery.

Purpose of the Study

Evaluating the prevalence of body dysmorphic disorder and severity of social physique anxiety in patients undergoing medical aesthetic treatment.

Research Questions

Is there significant difference in mean of social physique anxiety between case and control group?

Purpose of the Study

The current study was performed to compare the Social physique anxiety and body dysmorphic disorder in the group undergoing medical cosmetic treatments and the control group.

Research Methods

The method used in this study was a post-causal or causal-comparative approach. The study population included individuals requesting medical beauty treatments as referred to above, and students of Babol University, who were interviewed in 2014. The sampling method used in this study was available sampling in those subjects undergoing treatment and simple random sampling in the ordinary ones. The entire population included 400 individuals: 200 under medical beauty treatments and 200 normal subjects.

Tools for data collection

Three questionnaires were used to measure the variables in this study:

- Social Physique Anxiety Scale, Hart et al. (1989): this is a self-report 12-item scale, which is scored based on the five-value Likert scale. The reliability and validity of this scale was evaluated by Tabatabaeyan et al. in 2009, and its Cronbach's alpha was obtained as .083 (Samari & Lalifaz, 2005).

- Body Dysmorphic Disorder Questionnaire (BDDQ): was developed based on DSM-IV diagnostic criteria. This self-report scale is an instrument for the assessment of a person's concern about an aspect of his/her appearance that seems uninteresting to him/her (28). Studies show that there is a lot of coordination between medical diagnosis and the results of the questionnaire for the diagnosis of body dysmorphic disorder. Phillips et al. of Harvard Medical School showed that BDDQ meets appropriate psychometric characteristics (29).

- Social Acceptance Scale: has 33 questions, which are answered as True or False. Its reliability coefficient with re-test procedure was higher than 0.80. Regarding validity, the scale has demonstrated high and acceptable correlation with other psychological tools developed for measuring social acceptance (30) (Hatfield, 2002; as cited in by Samari & Lalifaz, 2005).

Findings

In the present study, the participants from the under beauty treatment group answered the questionnaires in private beauty clinics while the control group completed them individually at the university. First, both groups completed the testimonial acknowledging they were participating consciously in the study and then answered the questionnaires individually. The assessment of each group took no longer than one month. A psychotherapy interview was used in order to confirm the diagnosis of body dysmorphic disorder in those who had met the criteria of DSM-IV-TR based on BDDQ. All primary assessments were performed by a psychologist. Data were analysed using SPSS software, version 22. The statistical tests used to analyse the gathered data included mean, t- test, square, coefficient correlation, regression analysis and covariance analysis. The dependent or predicted variable was the rate of physical-social anxiety (scores of the Heart questionnaire) while the presence of body dysmorphic disorder, beauty surgery and referring to clinics to receive beauty services constituted the independent or predictive variables.

The demographic features of the individuals in the under beauty treatment group and the normal individuals of the control group have been presented in Table 1. The gender, age, education, marital status and professional state characteristics of the two groups were not equal. Therefore, covariance analysis was performed to investigate the effects of different demographic features on the disorder. The results showed that none of these features in either of the study groups had a significant effect on social physique anxiety.

Table 2 presents the distribution of social physique anxiety in the two study groups. The number of individuals in mild to moderate levels of anxiety was higher in the under beauty treatment group compared to the control group.

However, it was evident that the level of social physique anxiety in the under beauty treatment group (mean=26.59) was significantly lower compared to the control group (mean=28.19) (sig=0.05; t=-2.256). In other words, although in the control group fewer individuals were in the minor and moderate classes of social physique anxiety, the severity of this kind of anxiety was higher among them. Table 3 shows the mean of the under beauty treatment group and the number of subjects with body dysmorphic disorder and those seeking a cosmetic surgery.

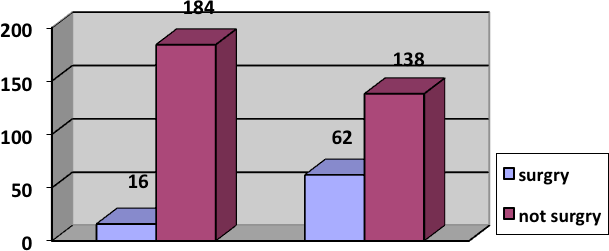

Findings indicated that 69% (n=138) of the under beauty treatment group did not have any surgery while 31% (n=62) had undergone some form of cosmetic surgery. In the control group, these numbers were 92% (n=184) and 8% (n=16), respectively. Diagram 1 shows the number of subjects with a surgery, separately. Square featured a significant difference between the two groups regarding the number of those having undergone surgery (sig=0.001; x2=33.7).

It was revealed that the number of individuals with body dysmorphic disorder was significantly higher in the under beauty treatment group (sig=0.04; x2=4.23). 19.5% of the subjects in the under beauty treatment group and 12% of those in the control group demonstrated some criteria for diagnosis of body dysmorphic disorder.

There was a significant difference in individuals with and without BDD regarding the levels of social physique anxiety in all subjects (t=-4.83 sig=001) and in the under beauty treatment and control groups, separately (control: sig=001, t=3.77; Treatment sig=001, t=3.33). Having body dysmorphic disorder was accompanied with high levels of social physique anxiety in both groups. In the under beauty treatment group, there was a significant correlation between the levels of social physique anxiety and body dysmorphic disorder, both in women (r=0/247 sig=002) and men (r=0/290 sig=0/04). In the control group, the relationship between the levels of social physique anxiety and body dysmorphic disorder was not significant in men (r=0/198 sig=0/09), but in women (sig=0/004 r=0/256).

In the control group, those who had surgery, experienced lower levels of social physique anxiety (mean=26.56) in comparison to those without it (mean=28.33); nonetheless, this difference was not significant (t=1.02 sig=0.3). No significant difference was revealed between the mean of social physique anxiety in subjects with (mean=26.19) and without (mean=26.77) surgery (sig=0.61 t=0.49).

The highest mean of social physique anxiety was appertained to women of the control group, who had body dysmorphic disorder but had not undergone any treatment (mean=33). The lowest mean of social physique anxiety also belonged to men of the under beauty treatment group who did not suffer from BDD (mean=24.43). The results of regression analysis showed that having body dysmorphic disorder (t=5.04 sig=0.001) and the lack of beauty treatment seeking (t=2.6 sig=0.009) were the highest predictors of social physique anxiety. Nevertheless, gender (sig=0.33 t=0.96) and having surgery (sig=0.47 t=-0.71) could not predict social physique anxiety. The results of regression analysis were presented in Table 4.

Conclusion

In the present study, 400 individuals in two groups of people referring to beauty clinics and the normal ones were investigated. The mean age of the subjects in the under treatment group and the control group was 27.8 and 21.9, respectively. In a study conducted by Will, the start age of body dysmorphic disorder was reported to be 16±7 and its diagnosis was under 30 years (Veale et al., 1996). These findings show that the distance between the beginning of the disorder and its diagnosis is long and people suffer from this disorder while tolerating it for a couple of years without receiving any aesthetics or psychological treatments. The difference in the mean age of the two study groups may also indicate the gap between disorder’s onset and its treatment (Veale et al., 1996).

It was observed that the number of individuals suffering from body dysmorphic disorder was significantly higher in the under beauty treatment group. 19.5% of those in the under beauty treatment group and 12.5% of those in the control group were diagnosed with body dysmorphic disorder. Sarwer investigated body dysmorphic disorder in people seeking cosmetic surgeries or other medical beauty treatments. His findings showed that 5-15% of those who were seeking medical aesthetics treatments were suffering from body dysmorphic disorder (Sarwer & Spitzer, 2012). In addition, the study of Philips revealed the higher rate of this disorder in reference to beauty treatments in comparison to the normal population. He also reported that 2.2-13% of students and 4-9% of patients seeking treatment with skin surgery, as well as 3½-50% of patients seeking beauty surgery have been diagnosed with BDD (Phillips, 2005; 2009). In a study performed among the students of the Medical Sciences Schools in Iran, the prevalence rate of BDD was reported 7.4% (Talaei et al., 2006). The number of individuals with BDD was high in this study, which is consistent with the results of Sarwer and Spitzer (2012), Phillips (2005), Phillips (2009). High rates of this disorder in candidates for medical beauty services may derive from the lack of exact scales for determining the A criterion of DSM-IV-TR in body dysmorphic disorder. As judgment about aesthetics abnormalities is a partial and subjective matter, the A criterion for diagnosis of this disorder is influenced by the clinical judgments of the therapist and his/her definition of aesthetics abnormalities.

Furthermore, no significant difference was observed between men and women regarding the affliction of BDD, which was in line with the findings of Talaei et al. (2006), Phillips (2009). A higher rate of women in the under beauty treatment group is also in line with the idea that women pay more attention to beauty (especially facial beauty) in comparison to men, and they seek beauty aesthetics or treatments more than men. Perhaps this is more closely related to cultural factors and the definition of manhood in Iran. However, when the psychological disorder of BDD is considered, cultural issues become a little colourless, as anxiety derived from BDD is so high that it occupies the patients’ minds excessively, disturbs their functions and, finally, encourages both genders to seek (more aesthetics but not psychological) treatments.

According to the findings of this study, the rate of social physique anxiety was significantly different in the subjects of the under beauty treatment group and those of the control group. In fact, individuals in the under beauty treatment group experienced lower levels of this kind of anxiety. In other words, therapeutic proceedings regardless of the kind of therapy can decrease an individual’s anxiety. Those who experience high levels of social physique anxiety but do not seek any kind of treatment suffer from higher levels of anxiety. The highest rate of Social physique anxiety in this study belonged to women of the control group who despite having body dysmorphic disorder had not received any prior treatment. In contrast, the lowest level of anxiety was attributed to men in the under beauty treatment group who did not have BDD. The question that arises here is how long the reduction of Social physique anxiety caused by receiving medical beauty treatments lasts, and if psychotherapeutic and psychological treatments have the same effect on the decline of this kind of anxiety. More research is needed in this area.

Having body dysmorphic disorder was accompanied by high levels of Social physique anxiety in both groups. In the under beauty treatment group, there was a significant relationship between BDD and Social physique anxiety in men and women. In the control group, the relationship between Social physique anxiety and body dysmorphic disorder was significant in women but not men. These findings are similar to those of Russell (2002). He investigated Social physique anxiety in men and observed that high levels of Social physique anxiety are accompanied with high levels of body dissatisfaction and low self-confidence (Russell, 2002). They are also comparable with the findings of Jennifer's study, which showed that people with significant symptoms in body image disorder experienced high levels of depression, stress, anxiety and suicide (Dyl et al., 2006). Given the B and C criteria of DSM-IV-TR for diagnosis of BDD, high co morbidity of body dysmorphic disorder with anxiety can be explained. However, those with high levels of Social physique anxiety without meeting the criteria for diagnosis of body dysmorphic disorder should be focused on more. These individuals do not meet the criteria for being diagnosed with BDD, but their levels of anxiety about this matter are very high. More research should be done to explain the Social physique anxiety of these individuals.

In the control group, the levels of Social physique anxiety were lower in those who had undergone at least some form of cosmetic surgery in comparison to those without it, albeit this difference was not significant. No study was found investigating levels of Social physique anxiety in individuals who are candidates for cosmetic surgery. In any case, many questions arise about the anxiety of these individuals, such as the level of anxiety before a surgery and the possibility of recurrence post-surgery and its related factors. More studies should be conducted to identify the issues in this area.

The results of regression analysis revealed that having body dysmorphic disorder and no beauty treatments was the highest predictor of social physique anxiety. Yet, gender type and having a surgery were not predictive. These findings can be explained as such: levels of social physique anxiety will be reduced in those referring to beauty clinics, which is their short-term coping strategy for managing their appearances (Mancuso, Knoesen, & Castle, 2010; Phillips, 2009). Mancuso et al. stated that although individuals with BDD may be able to reduce their anxiety in the short-term, it becomes chronic and deteriorates over time (Mancuso, Knoesen, & Castle, 2010). In order to a more comprehensive understanding of this issue, follow-up studies are required.

Generally, it can be said that social physique anxiety requires interventions and medical beauty treatments, as well as psychological treatments. In this study, levels of social physique anxiety were significantly different in the under beauty treatment and control groups, meaning that subjects in the under beauty treatment group had lower levels of social physique anxiety. Having body dysmorphic disorder and while not seeking any treatment was the highest predictor of social physique anxiety, while gender type and having a surgery had no prediction power. No significant difference was found in the levels of social physique anxiety in individuals with or without a history of some form of cosmetic surgery.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the medical beauty experts of Babol city, who provided sincere cooperation in conducting the present study. In addition gratitude is extended to all those patients and students of the Medical Sciences University and the Noshiravani University of Babol who participated in this study and completed the questionnaires honestly.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV-TR. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

Anson, M., Veale, D., & de Silva, P. (2012). Social-evaluative versus self-evaluative appearance concerns in Body Dysmorphic Disorder. Behaviour research and therapy 50(12), 753-760. DOI:

Brown, T. R. (2000). Does Social Physique Anxiety Affect Women’s Motivation to Exercise. Department of Psychology, 219-224.

Cox, A. E., Ullrich-French, S., Madonia, J., & Witty, K. (2011). Social physique anxiety in physical education: Social contextual factors and links to motivation and behavior. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 12(5), 555-562. DOI:

Davison, T. E., & McCabe, M. P. (2005). Relationships between men’s and women’s body image and their psychological, social, and sexual functioning. Sex roles, 52(7-8), 463-475. DOI:

Dyl, J., Kittler, J., Phillips, K. A., & Hunt, J. I. (2006). Body Dysmorphic Disorder and Other Clinically Significant Body Image Concerns in Adolescent Psychiatric Inpatients: Prevalence and Clinical Characteristics. Child Psychiatry Hum Development, 36, 369–382 (2006). DOI:

Fitzsimmons-Craft, E. E., Harney, M. B., Brownstone, L. M., Higgins, M. K., Bardone-Cone, A. M. (2012). Examining social physique anxiety and disordered eating in college women. The roles of social comparison and body surveillance. Appetite 59(3), 796-805. DOI:

Grieve, F. G., Jackson, L., Reece, T., Marklin, L., & Delaney, A. (2008). Correlates of social physique anxiety in men. Journal of Sport Behavior, 31(4) 329-337.

Hart, E. A., Leary, M. R., & Rejeski, W. J. (1989). The measurement of social physique anxiety. Journal of Sport and exercise Psychology, 11(1), 94-104. DOI:

Kolahi, P. (2009). Comparison of Depression and Anxiety in cosmetic surgery candidates and normal, National Conference on Student Social Factors Affecting Health, Tehran, Iran University of Medical Sciences.

Kruisselbrink, L. D., Dodge, A. M., Swanburg, S. L., & MacLeod, A. L. (2004). Influence of Same-Sex and Mixed-Sex Exercise Settings on the Social Physique Anxiety and Exercise Intentions of Males and Females. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 26(4), 616-622. DOI:

Lim, M. O. (2013). Intrusive imagery in body dysmorphic disorder.

Mancuso, S. G., Knoesen, N. P., & Castle, D. J. (2010). Delusional versus nondelusional body dysmorphic disorder. Comprehensive psychiatry, 51(2), 177-182. DOI:

Pernick, Y., et al. (2006). Disordered eating among a multi-racial/ethnic sample of female high-school athletes. Journal of Adolescent Health, 38(6), 689-695. DOI:

Phillips, K. A. (2005). The broken mirror: understanding and treating body dysmorphic disorder. Oxford University Press.

Phillips, K. A. (2009). Understanding body dysmorphic disorder. London, UK: Oxford University Press.

Phillips, K. A., Dufresne, R. G., Wilkel, C. S., & Vittorio, C. C. (2000). Rate of body dysmorphic disorder in dermatology patients. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 42(3), 436-441. DOI:

Reese, H. E., McNally, R. J., & Wilhelm, S. (2011). Probabilistic reasoning in patients with body dysmorphic disorder. Journal of behavior therapy and experimental psychiatry 42(3), 270-276. DOI:

Russell, W. D. (2002). Comparison of self-esteem, body satisfaction, and social physique anxiety across males of different exercise frequency and racial background. Journal of Sport Behavior, 25(1), 74–90.

Samari, A., & Lalifaz, A. (2005). Effectiveness Of Life Skills Education on Family Stress and Social Acceptance. Journal Of Fundamentals of Mental Health, 7(25-26), 47-55. https://www.sid.ir/en/journal/ViewPaper.aspx?id=85190

Sarwer, D. B., & Spitzer, J. C. (2012). Body image dysmorphic disorder in persons who undergo aesthetic medical treatments. Center for Weight and Eating Disorders. Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, 32(8), 999-1009. DOI:

Stuart, G. S., & Grimes, D. A. (2009). Social desirability bias in family planning studies: a neglected problem. Contraception, 80(2), 108-112. DOI:

Talaei, A., & Fayyazi Bordbar M. R., et al. (2006). Evaluation of Prevalence of Body dysmorphic disorder in MUMS students. Thesis and published in Journal of Mashhad Faculty of Medicine.

Veale, D., Boocock, A., Gournay, K., Dryden, W., Shah, F., Willson, R., & Walburn, J. (1996). Body Dysmorphic Disorder: A Survey of Fifty Cases. British Journal of Psychiatry, 169(2), 196-201. DOI:

Weinberg, R. S., & Gould, D. (2011). Foundations of sport and exercise psychology. Human Kinetics.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.