Teachers' Attitudes Towards Inclusion of Special Needs Children Into Primary Level Mainstream Schools in Karachi

Abstract

The purpose of this study was to explore the perceptions of regular and special education teachers towards inclusion of special needs children into mainstream schools and to account for any differences in those perceptions. The study also aimed to investigate how these teachers' attitudes impact the implementation of inclusion into the regular education classroom. This study sampled 55 teachers from several elementary schools in Karachi. The instrument utilized for the study was the Opinions Relative to Integration of Students with Disabilities (ORI), a six-point Likert attitudinal scale, developed by Antonak and Larrivee (1995). The main finding of the study revealed that there was no significant difference in the perceptions of special education teachers and regular teachers with regards to the benefits of inclusion.

Keywords: Teacher attitudes, special needs children, mainstream schools, inclusion, primary level

Introduction

The inclusion of students with special needs in mainstream education has been a major cause of concern for many governments around the world. It is a national and international development that is supported in national legislation and in statements and reports that have been issued by international bodies such as the United Nations and Council of Europe. The Salamanca Statement (UNESCO 1994) advocated that children with special educational needs (SEN) should have access to mainstream education so as to provide a basis to combat discriminating attitudes. The statement is therefore conceived as forming the basis for inclusion and a shift from segregation by creating a welcoming community, building an inclusive society and achieving education for all.

Inclusive education is a key policy in a number of countries, including the UK and US. The New Labor Government in the UK addressed the issue through its Green Paper within a few months of taking office. A major driver of all these efforts and developments has been concern that children’s rights are being compromised by special education. This is because these special children are segregated from their typically developing peers and the mainstream curriculum and educational practices. Here, the issue of the actual effectiveness of the different educational approaches has been a matter of concern for some other time. Most of the studies on the effectiveness of special education is based on empirical research. We believe that the issue should be primarily determined through the perspective of values and ideologies which promulgates that all humanity is equal and therefore everyone, whether disabled or not, should have an equal right to education. (UNESCO, 1994, Statement, p. 9)

The last census done in 1998 shows that of the total population in Pakistan, 2.54% is disabled in some form. This amounts to a total of 3,286,630 people. However, even this value is very small as it ignores those who are mildly disabled. The highest number of disabled is in Punjab (1,826,623), followed closely by Sindh (929,400). Of the total number of people disabled, 0.82 million are children between the ages of 5-14. This is 24.8% of the population with disability (Bureau of Statistics, 1998). This data is more than 17 years old now and can be used only as a rough gauge to determine of the current scenario in Pakistan as a thorough search has revealed that current statistics dealing with this group is non-existent. It can be assumed that this percentage would have increased in tandem with the increase in population throughout the world in the last 17 years. The point here is that, with the increase in numbers of special needs children, people have become increasingly aware that all children have the right to education. Therefore, more schools for special needs children were opened up and today increasingly, people have become aware of mainstreaming.

It is a fact that special children (either physically or mentally disabled) face many problems in life. Adults, in special needs children’s environments, whether they are parents or teachers, play an extremely important part in the physical and mental health of such children. At times, a team of specialists such as occupational therapists, speech therapists and aid teachers are required to help a special child to grow and develop. School is an important part of each child’s growth, and it is a God-given right that every special child receives an equal opportunity to education as with all the other children their age. This research will look into the schools in Karachi (Pakistan) which offer the opportunity of mainstream education to special children and attempts to uncover teachers’ opinions about mainstreaming in Karachi. The three main aspects that will be looked into are 1) the teachers’ opinions about whether mainstreaming is beneficial; 2) integrated classroom management; and 3) general classroom teachers’ perceived ability to teach special children.

General classroom teachers need to be willing and able to teach special needs children in their classrooms. If these teachers are unwilling to teach special needs children or have unrealistically low expectations of themselves when considering teaching special needs children, mainstreaming will not be successful. Therefore, finding out about the teachers’ existing opinions is of vital importance before actually starting mainstreaming. Special needs children deserve proper education; they have a right to it, and those who are able to work in the normal classroom environment should be included in it. As teachers who are willing to teach these children would face many challenges and issues, they may need specialised training, and they definitely need to have or develop many personal attributes such as patience to deal with these children. To achieve this, these teachers need to work with special needs children and be aware of the inherent challenges as well as changes it could lead to (Coles, 2009).

Literature Review

Adjustment of special needs children in primary schools

A study conducted by Hatamizadeh, et al (2008) on the effects of the inclusion of hearing impaired children in primary schools in Tehran revealed that in most of these hearing impaired children, the scale of hearing loss ranged from mild to moderate. The schools for this sample’s mainstream education were chosen by parents and were in close proximity to the child’s home. In these schools, in addition to the regular facilities that were provided to every student, each child with special needs received help from a specially-trained teacher for few hours a week. This study reveals that successful mainstreaming is dependent on extant factors like location of school, parental choice, and the assistance of specially-trained teachers.

Teachers’ opinions about inclusive education

Research about the teachers’ opinions on inclusive education as well as the teachers’ willingness and ability to teach special children have come up with mixed results. However, there is no conclusive evidence on whether the teachers’ personal opinions directly affect the results of including special needs children in mainstream schools. Although, most teachers do agree that special needs children should be included in mainstream schools, they also feel that problems may arise because of the inclusion of special children, such as knowledge barriers in the class. Apart from this, some teachers feel that they are not sufficiently qualified to handle special children and fulfil all their needs to ensure that they are educated in the best way possible (Hines & Johnson, 1997).

However, teachers also claimed that it was quite likely for the special needs students to display behavioural troubles in class and that these problems would have a negative effect on the other children in the class. They also claimed that it was harder to divide their time adequately between the special child and the rest of the students as well as keep the class disciplined when a special needs child was present in the class (Bahn, 2009). Overall, studies in this area revealed that the teachers were not very confident about their ability to teach special needs children.

Challenges teachers face with regards to the inclusion of special needs children

Teachers face many challenges when dealing with children in mainstream schools. Not only do they have to give the children quality education, they also have to ensure the safety and wellbeing of these children. However, when special needs children are included in the classrooms, the challenges would understandably increase. According to a study by Coles (2009), the first challenge that teachers have to face is personal. They have to maintain order, stay unbiased, and maintain enthusiasm, patience and respect. The teacher must make sure to give special needs children an equal opportunity and help them achieve their full potential but not at the expense of the other children which can prove to be a real challenge. They must make sure that the special child is not given undue preference over the other children and vice versa. It is essential that the teacher not exhibit personal biases. Teachers have to be fair in the classroom environment so that knowledge is disseminated fairly to all the students.

Research on Teacher Attitudes towards Mainstreaming

In 1979, Larrivee and Cook developed an instrument to measure teacher attitudes toward mainstreaming called the Opinions Relative to Mainstreaming (ORM) scale containing 30 items scored on a 5-point Likert scale. The purpose of the scale was to measure teacher attitudes toward the government mandated law of mainstreaming special needs learners into the regular classroom. This scale was first used to study teachers in the New England States (Cook & Larrivee, 1979). In 1995, Antonak and Larrivee revised the ORM to make it more contemporary and easier to use. The responses were reformatted to ensure validity. The scale was revised to a 6-point Likert scale and was renamed the Opinions Relevant to the Integration of Students with Disabilities or ORI (Antonak & Larrivee, 1995). In 1996, the ORI was used to study teacher attitudes toward inclusive education. The study found that teacher attitudes were neutral with regards to inclusive education (Jobe, Rust, & Brissie, 1996). A study conducted in 2001 in the Midwest, US of 69 classroom teachers in an urban setting also returned neutral results (Loomos, 2001). The current study attempts to replicate these studies to see if the previous findings as scored by the ORI still hold true for classroom teachers today.

Successful Implementation of Inclusion

According to Sands et al. (2000), “Creating and maintaining an inclusive school community requires an emphasis on a feeling of belonging and meaningful participation, the creation of alliances and affiliations, and the provision of mutual, emotional, and technical support among all community members” (p. 116). For many years, special education services separate from the mainstream were provided to special needs students. These students were usually excluded from typical interactions experienced by their peers and were not considered part of mainstream educational development. Feeling included and participating in the events and activities of the mainstream school community are equally important for all students. Inclusion allows all students to be accepted members of their school community.

Purpose of Study

The objective of this study is to analyze the perceptions of mainstream and special needs teachers with regard to the inclusion of special needs children in mainstream schools in Karachi.

Methodology

In order to analyze the perceptions of mainstream and special teachers with regard to the inclusion of special needs children in mainstream schools in Karachi, data was collected from the sample based on the following 5 dimensions:

- General Philosophy of Mainstreaming (eight items)

- Classroom Behavior of Special Needs Children (six items)

- Perceived Ability to Teach Special Needs Children (three items)

- Classroom Management of Special Needs Children (four items)

- Academic and Social Growth of Special Needs Children (four items)

Research Design

This study utilized the quantitative approach. When deciding what types of instruments to use, a quantitative researcher would tend to emphasize those that produce data that can be quickly reduced to numbers. The researcher would then interpret results of statistical analyses that were conducted and attempt to relate these results to the objective of the study (Creswell, 1994). In this case, the objective of the study is to provide a quantitative analysis of the perceptions of mainstream and special teachers with regards to the inclusion of special needs children in mainstream schools in Karachi.

Instrumentation

The instrument used for this quantitative research is the Opinions Relative to Integration of Students with Disabilities (ORI) scale. The ORI is appropriate for this study because it measures the attitudes of regular and special education teachers toward inclusion. Larrivee and Cook (1979) developed the Opinions Relative to Mainstreaming Scale (ORM), an earlier scale, as part of a large sample investigation of teachers’ attitudes toward mainstreaming students with disabilities into general classrooms. A pilot survey was done with four mainstream & special teachers. Following this, two changes were made in the questionnaire. The first was to identify those students who were mildly disabled as the selected teachers said that it would be impossible for a severely disabled child to work in an ordinary school environment. Secondly, as per the suggestions of the teachers, another question was added in the survey, just for special needs teachers, asking whether they believed that the general teachers lacked proper training to teach special needs children.

Hypothesis

The three main aspects that will be looked into are 1) the teachers’ opinions about whether mainstreaming is beneficial; 2) integrated classroom management; 3) general classroom teachers’ perceived ability to teach special children. As such, the following hypotheses were formulated:

Ho: There will be no statistical difference in the perceptions of the special education teachers and the general education teachers regarding the benefits of inclusion.

Ha: Special education teachers would perceive that integration is more beneficial as compared to general education teachers.

Ho: There will be no statistical difference in the perceptions of the special education teachers and the general education teachers regarding integrated classroom management strategies.

Ha: general education teachers would find integrated classroom management more challenging compared to special education teachers

Ho: There will be no statistical difference in the perceptions of the special education teachers and the general education teachers regarding their ability to adapt instruction to students with disability.

Ha: special education teachers would have a lower perception regarding the ability of mainstream teachers to adapt instruction to students with disability.

Sample

The sample comprised 55 teachers from the city of Karachi, Pakistan; 31 were General Education teachers (56.4%), and 24 were Special Education teachers (43.6%) from special schools like the Institute of Behavorial Psychology (IBP), Special Children Educational Institute (SCEI), Manzil School, and Darul Sukun. The 31 mainstream teachers were from schools like Aasma Montessori, Haque Academy, CAS, Bayview, and Beaconhouse. The scale used to study the perceptions of the teachers in this study is the Opinions Relative to the Integration of Students with Disabilities (ORI). This is a 6 point Likert scale which is the revised version of the Opinions Relative to Mainstreaming (ORM) scale developed by Richard Antonak and Barbara Larrivee (1995). In total, there are 25 items in this scale based on the dimensions as stated below in Table 1.

Findings & Discussion

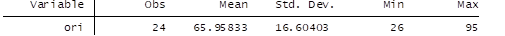

For the analyses, a total of 2 observations were dropped, since one of them seemed to be done by the same teacher and the questionnaire that was dropped had more than four items unanswered in the ORI instrument. The means and standard deviations of the five subscales used in this study can be found in Table 2 below.

Table 2 shows the mean scores of the teachers on each of the five subscales. The first scale is the Benefits of Integration (BOI) Scale which actually measures the teachers’ perceptions relating to if they feel inclusion of special children in the general classroom environment is advantageous. This scale includes questions like and The overall score that each teacher can receive in this section ranges from 0 to 48. This means that scores from 0 to 24 represented negative attitudes to inclusion, whereas 24 to 48 represented positive attitudes towards inclusion. The mean score that was calculated for the teachers in this category was 28.8 which is above 24. This means that most teachers including both general as well as special education teachers feel that proper integration could prove to be advantageous.

As for the second category in Table 2, that is integrated classroom management (ICM), questions related to the changes that would be brought about in the general classroom environment included and The mean score of the teachers in this category was 24.3 from a given score range of 0 to 60. This score lies in the range of 0 to 30 which reveals that the teachers have a negative attitude regarding this factor. They feel that it is very likely that integration will require significant changes to be made in the general classroom procedures. Students with disabilities would exhibit behavioural problems in the class which may also set a bad example for the other students. These mildly disabled students may also create confusion to some extent which would require the teachers to show increasing amounts of patience. Time spent sorting out issues caused by the presence of the special needs children in the classroom would have also led to most teachers giving this component a low score, meaning that integration will cause problems in managing the classroom environment.

The third component is the perceived ability of teachers to teach these special children. To get a score in this category, teachers had to respond to questions like and. The score of this component could range from 0 to 18. The mean score recorded by the teachers was 4.7 which lies in the range of 0 to 9. This means that most teachers feel that integration would require extensive retraining of the general education teachers, as they currently have very little formal training to handle these special children.

The fourth component was related to the preferences of teachers in terms of special versus integrated general education and the score could range from 0 to 24. The mean score in this category was 7.7 which lies in the range of 0 to 12, which means that most teachers feel that special education is more appropriate for the special needs children. This is because they will be given more time and attention by specially trained teachers who have the right training and attributes to deal with the challenges of teaching special needs children.

The overall ORI score is determined by the total of each of the above 4 categories which represents the overall opinions of the teachers regarding inclusion of special needs children in mainstream education, taking every factor into account. The total score of this category could range from 0 to 150. The mean score that was recorded by the teachers was 65.7. This lies in the range of 0 to 75, which means that overall, the teachers are hesitant towards the inclusion process. An interesting factor to consider is that, even though most teachers feel that integration is beneficial, close to 70% also stated that special needs children should go to special schools. This could be for a variety of reasons, but the main reasons seem to be that the inclusive classroom may be very difficult to manage and considerable changes would have to be made with general teachers believing that they have insufficient training to handle a special child in the class. Therefore, although teachers might feel that inclusion is beneficial but due to low scores recorded in the other three factors of integrated classroom management, perceived ability to teach and special versus integrated education, the overall opinion seems to favour non-inclusion.

The above findings will be used to provide evidence to verify the hypotheses of this study.

Hypothesis 1

1) Ho: There will be no statistical difference in the perceptions of the special education teachers and the general education teachers regarding the benefits of inclusion.

Ha: Special education teachers would perceive that benefits of integration are more beneficial as compared to the perceptions of the general education teachers.

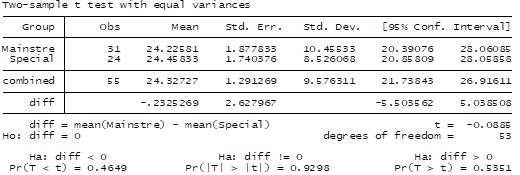

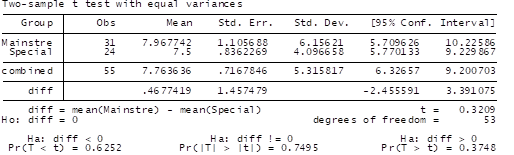

To study the differences within the perceptions of the special teachers and the general educators, a two-sample mean comparison test was conducted (t-test) on Stata 11.

Diff = mean (Mainstream) - mean (Special) t= 0.2257

Ho: diff = 0 degrees of freedom = 53

Ha: diff < 0 Ha: diff != 0 Ha: diff > 0

Pr(T < t) = 0.5889 Pr(|T| > |t|) = 0.8223 Pr(T > t) = 0.4111

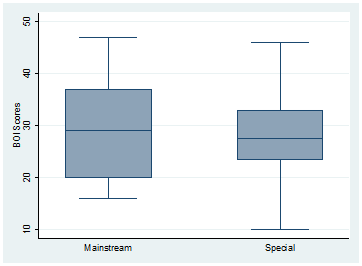

The sample of 31 general education teachers scored this item with a mean of 29.03226, with a standard deviation of 9.1887. The sample of 24 special educators scored this item with the mean score of 28.5, with a standard deviation of 7.95. Thus, the result of t value is 0.2257 & P value is 0.8223 for the null hypothesis. Since p>0.05, we can confidently accept the null hypothesis that there is no significant difference in the perceptions of the general and special educators relating to the benefits of integration and reject the alternate hypothesis. This is visually depicted in the boxplot (Figure 1) below.

Hypothesis 2

2) Ho: There will be no statistical difference in the perceptions of the special education teachers and the general education teachers regarding integrated classroom management strategies.

Ha: Special education teachers would perceive that integrated classroom management is more challenging as compared to the perceptions of the general education teachers.

To study the differences in perceptions of the two groups of teachers related to this component, another two-sample mean comparison test was conducted. The results are shown in Table 4 below.

Special education teachers scored this item with a mean of 24.45, standard deviation of 8.52. The mainstream teachers scored a mean of 24.225, standard deviation of 10.455. After carrying out the t test, t value of -0.0885 and p value of 0.9298 is realized. Since p>0.05, we can confidently accept the null hypothesis that there is no statistical difference between the perceptions of the two types of teachers related to integrated classroom management (ICM) and so reject the alternate hypothesis.

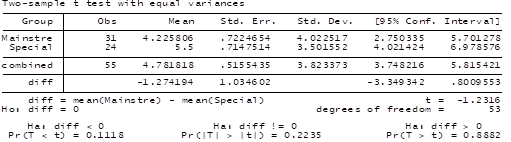

Hypothesis 3

3) Ho: There will be no statistical difference in the perceptions of the special education teachers and the general education teachers regarding the ability of general education teachers to adapt instruction to students with disability.

Ha: Special teachers would have a lower perception regarding the ability of general education teachers to adapt instruction to students with disability.

To find the difference in perceptions between both groups of teachers, two two-sample independent t-tests were conducted. Tables 5 and 6 below show the results.

For this factor, the special and the general education teachers had very similar means as well. Means were around 7 and the standard deviation was around 4 for special teachers and 6 for mainstream teachers. The t value of the test results 0.3209 and p value was 0.7495. Null hypothesis cannot be rejected as p is not less than 0.05. Therefore, the alternate hypothesis can be rejected.

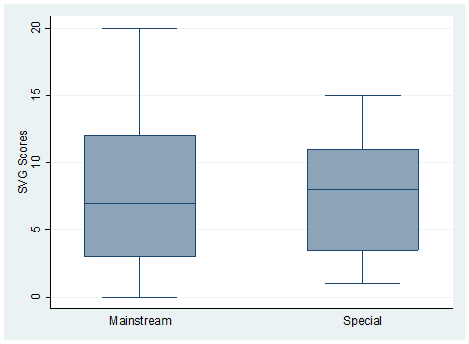

Below is the box plot for the component of Special vs Mainstream education.

The Box plot (Figure 2) shows that there is not much difference between the views of mainstream and special teachers. The mean scores are 7 approximately. The total score of this scalable vector graphics component could range from 0 to 24. In the 0 to 12 range, teachers feel that special children grow more academically and socially through special education, whereas in the 12 to 24 range, teachers feel that mainstream education is better for the child’s growth. The mean of the SVG component lies in the 0 to 12 range which means that both type of teachers feel that special education is better for the social and academic growth of the student with a disability.

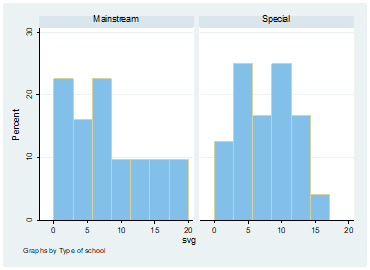

The histogram below shows the individual responses recorded for each type of teacher on the SVG component of the ORI scale.

These individual responses show that there are some mainstream teachers who have scored more than 12, meaning that they are in favour of general education for the disabled students. However most of the blue area of the graph for the special teachers lie below the 10 score mark. This again shows the high variance and deviation in the responses of the general teachers as compared to the low variance of the special education teachers' scores.

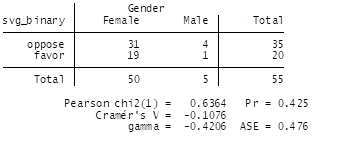

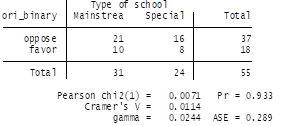

There is a further need to look into why there is a high variance in the scores for the general teachers. After looking into the Chi Square tests for different associations to highlight other variables that have an effect on the SVG scores (Table 7), it was found out that gender does play a small role in determining the perceptions regarding the SVG component.

However, results relating to gender analysis cannot be generalized because of the limited sample of male teachers.

Total ORI Scores

The total ORI scores for both the special teachers and the mainstream teachers are less than 75. The ORI score could range from 0 to 150. 0 to 75 represents the negative attitude of teachers towards inclusion, whereas 75 to 150 represent the positive attitudes of the teachers towards inclusion. In results showed above (Table 8), it is clearly evident that overall mean score of teachers reflect a negative attitude towards inclusion.

This is the final component which is the total of all the four subscales: BOI, ICM, PAT, and SVG. A chi2 test was applied to test for the association between the type of teacher/school and the total ORI score (see table 9). The p value result is 0.933 which means there is a weak association. This also fulfils the purpose of the research as it shows that teachers have negative attitude towards inclusion no matter the type of teacher.

As teachers who work with special needs children every day, they should have an accurate idea about the sort of training needed to handle special children. This result shows that for inclusion to take place in Pakistan it is imperative for the general education/mainstream teachers to undergo some sort of training that will enable them to work with special needs children more effectively.

Conclusions

The study has established that all four of the null hypothesis can be accepted. Firstly, the analysis showed that the perception of special education teachers and general education teachers was very similar with regards to the benefits of inclusion. Most of the teachers believed that inclusion of special needs children in mainstream schools was beneficial. The second hypothesis showed that there was no statistical difference in the perceptions of special education teachers and general education teachers about the classroom management techniques for integration. Both types of teachers felt that handling special needs children in the general classroom would be more of an effort and would require a lot of change in the classroom environment. The third hypothesis was also accepted as most of the teachers, both general and special felt that a significant amount of training will be necessary before inclusion is possible. The special education teachers had slightly lower expectations of the general education teachers to teach special needs children without extensive training. The fourth and last hypothesis was also proved to be true as both special education teachers and general education teachers had almost the same opinion about whether special needs children should go to mainstream schools or special schools. Both teachers agreed that special children have a better opportunity of progress if they are in special schools. Uncovering teachers' perceptions is important because the teachers are the ones who are in close contact with their students and usually have a lot of experience in dealing with them. The teachers, especially those who have taught special children before will understand the advantages and consequences of inclusion and their perceptions will provide valuable insights on whether inclusion should be pursued. However, on a cautionary note, there is still a lot of research that can be done before considering inclusion.

Implications and Recommendations

In today’s world, inclusion is becoming more of a reality worldwide and Pakistan is fast catching up. Even in Pakistan, it is not the norm anymore to ignore children with disabilities and consider them helpless. As the importance of education increases, so is the importance of educating special needs children. More and more parents want their children to be well educated whether they have special needs or not. At first, special needs children were sent only to special schools however, now, awareness about inclusive education is on the rise. Parents want their children to attend regular schools especially if their child is only mildly disabled, and access the same quality of education that other children are getting.

However, research has shown that inclusion can only be successful if the teachers are willing and able to teach the special needs children and actually believe that it is possible to include them in mainstream schools.

Therefore, the first step to encouraging inclusion in Pakistan is to find out the teachers’ opinions on inclusion of special needs children. If more teachers are willing and able to teach special needs children, there is a higher chance of a successful implementation of inclusion. However, in Pakistan, as this study has shown, although teachers do believe that mainstreaming is more beneficial, they perceive that they lack the confidence in teaching special needs children and believe that such children are still better off in special schools. Most teachers do not believe that inclusion can be implemented successfully unless there is also a resource teacher available. A resource teacher is one that is present in the class only to help in educating the special needs child.

Only after an accurate estimation of teachers’ opinions is made, can the process of introducing mainstreaming be taken to the next level. Therefore, it is of vital importance that the teachers’ opinions are investigated. Since teachers in Pakistan believe that special children should be in special schools, the reasons for such a perception should be looked into and accordingly, changes should be made. For example, most teachers feel that they lack the training to teach special needs children, so, to encourage inclusion, more training institutes should be opened up, or private schools can offer training. This will help make the process of inclusion smoother and the chances of success higher.

Keeping the limitations of this research in mind, there are numerous recommendations that come to mind.

Finding out about the teachers' opinions is the first step towards inclusion. To find out if most of the educators in our country are for or against inclusion will indicate what should be done for the special children population. This is because the teachers, both special and mainstream, are in close contact with their students and have a good idea what the children need or do not need to grow and become mature, individualized human beings. To actually incorporate inclusive education in Pakistan, the whole of Pakistan needs to be considered. Therefore, a research that includes the whole of Pakistan should be conducted as it would give more value to the results and at the same time provide a holistic view of the opinions of all the teachers in Pakistan. However, if this cannot be done, teachers' opinions about inclusion in the other major cities should be taken into account so that an approximate of the whole country can be provided. Only then will the government and private sector take the idea of inclusion seriously and consider implementing it.

This research shows that most of the teachers believe that it is beneficial for special needs children to attend mainstream schools. However, it also showed that, when comparing mainstream schools with special needs schools, most teachers said that the special needs children should attend special needs schools which is contradictory. Therefore, a research should be conducted on why this difference occurs and what can be done to resolve this divergence. It should aim to find out why exactly the teachers believe that special needs children should be in special schools but still think that inclusion would be beneficial.

Another recommendation is that a research can be conducted to see the difference between special needs children in special schools and in mainstream schools. Pairs of children with the same kind of disability could be observed in depth to find out whether the child in the special needs school is doing better compared to the child in the mainstream school. This research will support either inclusion or separation and will provide the government and the private sector with evidence as to which mode of education is actually more beneficial for disabled children.

This study can be replicated with more teachers and an increased number of schools along with more male teachers in mainstream schools so that there is no element of bias. Such research would also serve to establish the validity of this study in attempting to uncover teachers' perceptions of and support for inclusive education in Pakistan.

Acknowledgements

The author(s) declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

About.com. (2010). What Are "Special Needs"? Retrieved from http://specialchildren.about.com/od/gettingadiagnosis/p/whatare.htm

Allen, K. E., & Schwartz, I. (2000). The Exceptional Child: Inclusion in Early Childhood Education (4 ed.). Delmar Cengage Learning.

Antonak, R. F., & Larrivee, B. (1995). Psychometric analysis and revision of the Opinions Relative to Mainstreaming Scale. Exceptional Children, 62, 132-149.

Brooks, R. (1991). The self-esteem teacher. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service.

Bureau of Statistics (1998), Census of Pakistan (1998), Bureau of Statistics, Islamabad.

Coles, B. (2009). Top challenges teachers face in special needs inclusive classrooms, Helium, 1-7, Retrieved from http://www.helium.com/items/1616836-what-are-the-teachers-biggest-challenges-with-a-special-needs-inclusive-classroom

Cook, L., & Larrivee, B. (1979). Mainstreaming: A study of variables affecting teacher’s attitude. The Journal of Special Education, 13(3), 315-324.

Encyclo (n.d.). Mainstream education, accessed 16 June, Retrieved from http://www.encyclo.co.uk/define/Mainstream%20School

Express Tribune Pakistan. (2012). Government not ready to mix students with special needs at mainstream schools. Retrieved from:http://tribune.com.pk/story/343177/government-not-ready-to-mix-students-with-special-needs-at-mainstream-schools/

Force, D. (1956) Social status of physically handicapped children. Exceptional Children, 23, 132–135.

Investopedia. (n.d). Definition of special needs children. Retrieved from http://www.investopedia.com/terms/s/specialneedschild.asp#axzz1tS1NadLU

Jobe, D., Rust, J. O., & Brissie, J. (1996). Teacher attitudes toward inclusion of students with disabilities into regular classrooms. Education, 117(1), 148-154

Lindsay, G. (2007). Educational Psychology and its effect on inclusive education/mainstreaming. British Journal Of Educational Psychology, 77, 1-24.

Loomos, K. A. (2001). An investigation of urban teachers' attitudes toward students with disabilities in the least restrictive environment. Chicago, IL: Loyola University

Hatamizadeh, N., Ghasemi, M., Saeedi, A., & Kazemnejad, A. (2008). Perceived competence and school adjustment of hearing impaired children in mainstream primary school settings. Child: care, health and development, 34(6), 789–794.

Ripley, S. (1997). Collaboration between general and special education teachers. ERIC Clearinghouse on Teaching and Teacher Education, Washington, DC.(ERIC Document Service No. 409317.)

Runswick-Cole, K. (2008). Parents' attitudes to the inclusion of children with special educational needs in mainstream and special schools. British Journal of Special Education, 35(3), 173-180.

The Sands, D. J., Kozleski, E. B., & French, N. K. (2000). Inclusive education for the 21st century. United States of America: Wadsworth.

Schuum, J., Vaughn, S., Gordon, J., & Rothlein, L. (1994). General education teachers’ beliefs, skill, and practices in planning for mainstreamed students with learning disabilities. Teacher Education and Special Education, 17(1), 23-27.

Tvingstedt, A. L. (1993). Social condition of hard-impaired pupils in regular classes. Educational Resources Information Center (ERIC), EC 302 911.

Tvingstedt, A. L. (1995) Classroom interaction and the social situation of hard-of-hearing pupils in regular classes. Paper presented at the International Congress of Education of the Deaf. 18th, Tel Aviv, Israel, 16–20 July 1995.

UNESCO. (1994). Final Report: World conference on special needs education: Access and quality (Paris, UNESCO). United Nations Children’s Fund.Examples of inclusive Education (n.d.). Retrieved from http://icfe.teachereducation.net.pk/resources/res26.pdf

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Division for Social Policy and Development (2006). International Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, at www.un.org/esa/socdev/enable/rights/ahc8adart.htm.

Villa, R. A., Thousand, J. S. Meyers, H., & Nevin, A. (1996). Teacher and administrator perceptions of heterogeneous education. Exceptional Children, 63(1), 29-46.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.