Abstract

The question of the extent of readiness of all participants for remediation is critical for the success of the program. Readiness of students entering university education is increasingly becoming a serious matter of concern. Large numbers of students graduate from secondary education but many are underprepared for postsecondary work. They need to undertake college level education but find that they need remediation to proceed in their pursuit of tertiary education. The remedial program means taking longer in college, uncertainty regarding whether they will complete this level of education, additional financial costs, and negative attitudes. Many of these underprepared students are therefore left questioning whether they deserve to be in remedial classes. They are not the only group that needs to address readiness for remediation as a matter of significance; university lecturers, sponsors or guardians, the universities themselves, and the government, all need to assess their readiness at the onset of a remedial program. This paper explores the concept of readiness as a critical determinant of the success of a remedial program and demonstrates that remediation is beneficial as it enables students to tap into the benefits of university education. Remediation also enables nations to draw from the huge potential from students who would, without remediation, be kept out of careers. It concludes that remediation is important despite the attendant costs and attitudes.

Keywords: Remediation, readiness, underprepared students

Introduction

Remedial education (also referred to in the literature as developmental education for imparting developmental or basic skills) refers to courses taken on a college campus that are below college-level and mainly aimed at bringing students who were initially underprepared for college level education in writing and math up to the threshold for registration into credit-bearing courses (The Alliance for Excellent Education, 2011). The purpose of remediation is therefore to furnish the students with the key skills required to undertake university education. The students pay tuition and may access financial aid for remedial courses, but they do not receive college credit. Most remediation occurs in reading, writing and math and communication technology.

Studies have revealed that a large number of students entering universities and colleges are underprepared for the work at that level and therefore are in need of remedial or developmental education in English, Reading, Math and, lately, Information Technology. Haycock and Huang (2001), studying remedial education in the United States, place the numbers of those in need of remediation at 49 per cent of all freshmen entering 4 year colleges. The Alliance for Excellent Education (2011, p. 1) claims that “one out of every three students entering postsecondary education will have to take at least one remedial course” while Bettinger and Long (2008) estimate that by 2001, underprepared students entering post-secondary institutions in the United States were one third of the total number of students entering this level. At the USIU-Africa, for the eight semesters between Fall 2013 and Spring 2016, 5,278 (about 14%) out of a total of 37, 852 students admitted got remedial education in English Math, and Information Technology. These high numbers underscore the importance of successful remedial education in enabling these students to draw on the benefits that the knowledge, skills, and attitudes imparted at university empowers them with.

This paper identifies the cost of remediation, the lack of clarity in the concept and criteria of preparedness, lack of transition between secondary and post-secondary institutions in terms of what it takes to succeed in postsecondary work, lack of standardization of remedial assessment instruments and placement tests and what they focus on, and attitudes as the main factors that inhibit readiness for remedial education. It finally establishes that in spite of mixed thinking about the value of remediation, it is important in ensuring that students who would otherwise not have had university education do get it and go on to reap the benefits accruing from the knowledge, skills and attitudes that such education endows them with.

Readiness

Everyone involved in remediation needs readiness or preparedness. Readiness is understood in this paper as willingness or preparedness. For the students, readiness can be understood as their willingness to take a course to enable them to gain the skills necessary to complete college-level courses and academic programs successfully (Weissman et al., 1997). For the parent or sponsor of an underprepared student, readiness means a willingness to pay for a program seen to occur at extra cost and which does not count towards graduation of the student while for the taxpayer and government, readiness means willingness to pay twice – “first for students to learn material in high school and then again for students to relearn.” (Alliance for Excellent Education, 2011, p. 4). Concern with readiness is therefore not only limited to the student, but also involves related stakeholders like the sponsor and tax payer. The institution too, needs readiness to design and launch remedial courses and deploy teachers to teach a course that should have been assumed as a prerequisite for college work while teachers need readiness to teach courses amidst dismissive opinions expressed about their academic and professional standards.

In all these, readiness is a key requirement for the success of a remedial program. Without readiness, the students will not undertake a remedial program and will therefore miss out on the benefits of university education. A nation’s hope in its youth benefiting maximally from the education it finances will not be fulfilled when students do not get admitted into its colleges and universities because of under-preparedness. This study recognizes the benefits that university education exposes students to. It is these benefits that the underprepared student stands to lose if he or she does not take remedial education to enable him or her to access university education. And it is because of these benefits that all parties involved in education need preparedness to ensure that remedial education succeeds.

Problem Statement

Studies (Hancock & Huang, 2011; Bettinger & Long, 2008; and Alliance for Excellent Education, 2011; Onditi, 2014) suggest that a growing number of high school graduates who would be looking to join post-secondary institutions are underprepared for the academic challenge awaiting them at that level in terms of gateway disciplines like Writing, Math and Information Technology (Nasser & Goff-Kfouri, 2008). These are students who would successfully go through their university education and provide the much needed human resource for their countries if they were put through remedial education to give them skills that they are short of at this stage but which they need to participate competently and successfully in their university experience.

While the literature establishes that “…educationists are in agreement about the value of remediation in uplifting the skills of undergraduate university entrants”(Onditi, 2014, p. 1179), there is considerable resistance from the students themselves, their parents or sponsors, teachers, institutions, the tax paying public and the government to remedial education. Because it is these stakeholders who drive remedial education, its future would appear to be in jeopardy if nothing is done to sensitize them to the value of remediation. There is need therefore to study the attitudes of the stakeholders and the reasons that have been given in the literature and to venture solutions that would sustain the position of remediation in the education system.

Research questions

What role does cost of remedial education play in the reluctance of students other stakeholders to embrace it?

What role does attitude play in the resistance to remedial education by students and other stakeholders?

Research Methods

This study employs a design that is a mixture of quantitative and qualitative data analysis. A review of literature on remedial education undertaken and data was also collected from a survey done on a sample of 40 parents / sponsors who attended the Freshman Orientation of Summer 2016 and 50 underprepared students who took the remedial English course (ENG 0999) in the Spring Semester 2016 at the United States International University – Africa in Kenya. An analysis of the data is undertaken and reported in pie charts in the next section of this paper.

Data Presentation and Discussion

The following section presents data and literature that relates to the factors that inhibit the readiness of the stake holders to enable the successful implementation of remediation programs and to ensure that students enrolled in the programs pick up the required skills that facilitate their competent participation in the programs.

Factors that inhibit Readiness

University education brings many stakeholders together. For remedial education to succeed, the student, the parent or sponsor, the lecturer, the institution, and the government must all work together. Students undertake the studies while their parents, guardians or sponsors pay tuition, the lecturers deliver the programs developed and administered by the institutions. Lastly the government funds the education budget. It is because of the need to enable students to access university education that those who emerge from high schools underprepared are enrolled into remedial programs. Unfortunately, each of the stakeholders has a reason to resist remedial education. These stakeholders resist remediation programs because of what they perceive to be the educational value of the programs, the costs involved for students, parents or sponsors, teachers, the government and the institutions, and the attitudes that associated with them. This situation is exacerbated by results from studies that question the effectiveness of remedial education in enabling underprepared students to overcome their weaknesses, (Bailey, 2009). Alliance for Excellent Education (2011) also cites Calcagno et al. (2008) who report that the effects of remediation on postsecondary outcomes present remedial education as a poor substitute for a high-quality high school education.

Cost of Remediation

Perhaps the single most important factor affecting remedial programs and responsible for their discontinuation is cost. Costs of remedial education are a concern for parents or sponsors, institutions and government. As long as remediation is seen to occur at extra cost, it is likely that parents, institutions and governments would not see value in investing in it. The cost of remediation is high. There are no statistics to show how much is spent in Kenya on remedial education because most of the remedial education is sought by sponsors privately and some of it is banned by the state. In the United States, however, the advocacy group, Alliance for Excellent Education, estimates it at 3.6 billion US dollars yearly. This is even more so when the statistic of success of remedial education is taken into consideration. The Alliance for Excellent Education cites the US Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics which reports that 43 per cent of students who begin postsecondary education fail to graduate with a degree after six years.

When this happens the tax payer’s money “becomes a lost investment” or sponsors are not convinced they need to shoulder the high cost of remedial classes. Bettinger and Long (2008, p.2), citing the Ohio Board of Regents (2001), report that in Ohio, “public colleges spent approximately $15 million teaching 260,000 credit hours of high school level courses to freshmen in 2000; another $8.4 million is also spent on older students.” Other estimates of the cost of remedial education by Sandham (1998), Manzo (1996), Ponessa (1996) and Ignash (1997) quote 10 million dollars for California, 155 million dollars for Texas, 32 million dollars for Louisiana, 50 million for New Jersey, and 18.7 million dollars for Oklahoma. Bettinger and Long (2008) also add to the fears of guardians and students by claiming that remediation may be harmful because it increases the number of requirements and lengthens the time it takes to graduate which in aggregate may lower the likelihood of degree completion.

At the United States International University Africa, as table 1 below reveals, between the Fall 2013 semester and Spring 2016, 5,278 (about 14%) out of a total of 37, 852 students admitted got remedial education in English Math, and Information Technology and paid a total of 22,113,250 Kenya shillings to finance their remedial programs. A normal 4 course menu for one student would have cost 696,000 Kenya shillings for the eight semesters and 3,673,488,000 for the 5,278 students who took remedial intervention in the period. Remediation thus cost 101,834,000 for these students and approximately 2.8% of what mainstream courses cost. Because remedial intervention delayed students’ graduation time, they perceived that the fees they paid to undertake it as an unnecessary cost.

The cost of remediation is not only a burden parents and sponsors struggle with, even governments also resist the funding of remediation particularly because of the fact that the need for remediation is growing. According to Jacobs (2012), a number in excess of 60 percent of first-year students at Dayton, Ohio's Wright State University were underprepared for college-level reading and writing, or math. Jacobs (2012) reports that from the Fall of 2012, Wright State would send their "developmental education" students to nearby community colleges like the Clark State Community College or Sinclair Community College while Ohio state planned to stop providing funds for most remedial university classes by 2014. It was expected that this would affect more than a third of first-year students who were entering university that year. Quite a good number of governments do not have a budget for remedial education or have informal arrangements of the kind called tuition in Kenya which the government neither takes responsibility for nor approves of. Some states in the United States (put at about more than a dozen) have restricted funding for remedial education at four-year institutions. For example, Oklahoma and Nevada do not give state funding to remedial education at four-year institutions.

With costs of remedial education as high as they are, more and more underprepared students looking to join college-level institutions and parents, sponsors and governments reluctant or downright opposed to funding remedial education, it would appear that every factor is in conspiracy to eliminate remedial education from the curricula of universities.

Instruments of Placement

Students entering colleges and universities are now routinely tested to determine whether they are ready for college level work over and above the results of their secondary schools examinations. Placement tests are administered to students who are already admitted to colleges. There are however variations in terms of methods of determining student placement among institutions. While some institutions use national college admissions exams, like the ACT or SAT, others require students to take a placement exam, such as Accuplacer or COMPASS 4, before they register for courses. At the end of the exam, the students who do not meet specified performance thresholds are placed in remedial courses. A large number of students however find placement in remedial education courses which they are required to take before they begin or together with regular college coursework.

Concept and Criteria of Preparedness

Preparedness is therefore made dependent on the placement exams selected or devised by each institution. However, there is no universally agreed concept of what college preparedness really means. Phipps (1998) points out the existence of evidence “… indicating that the standards for remediation vary considerably (even) within a set of institutions with similar missions” (p. vi). He additionally adduces evidence from a study by the Southern Regional Education Board (in the United States of America) that reports nearly 125 combinations of 75 different tests in use in placing students in remedial courses.

This incidence of under-preparedness has been blamed on lack of rigor in high school and the fact that high school students understand very little of what is expected of them in preparation for college. In the words of Bettinger and Long (2008, p.1), “high school graduation standards do not coincide with competencies needed in college”. This leaves the placement tests administered on admission to college the only gate-keepers to post-secondary study.

Barnett claims that there is a debate on what constitutes an acceptable amount of remediation. Students who get admitted into remedial programs are those who have failed to make the threshold in the placement tests or the approved instruments that enable them to get into regular university courses. The concept of what is required as preparation of students to merit admission without remediation is not clearly established. Additionally, what remediation should achieve and how much of it is required to achieve it is not very clear. In Kenya, for example, there is confusion between re-teaching and remediation where those involved in remediation or tuition give out a curriculum parallel to what schools or colleges give. Ideally, remedial teaching should proceed diagnostically; it should only address those aspects of knowledge, skills, and attitudes in which the students fall below the threshold for university work.

Attitudes

This section reports the results of the survey on a sample of 40 parents / sponsors who attended the Freshman Orientation of Summer 2016 and 50 underprepared students who took the remedial English course (ENG 0999) in the Spring Semester 2016 at the United States International University – Africa in Kenya. The survey sought answers relating to how well the students and their sponsors understood the importance of remedial courses and if they found value in remediation.

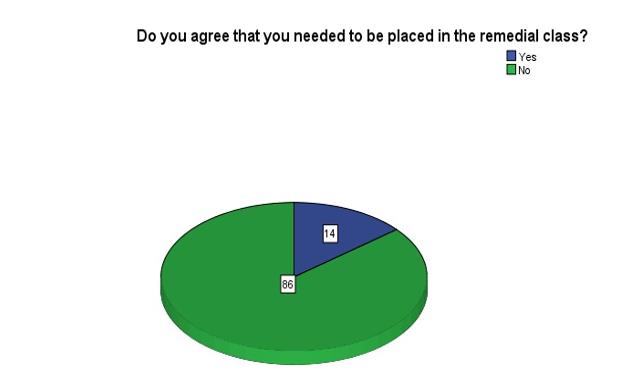

Students

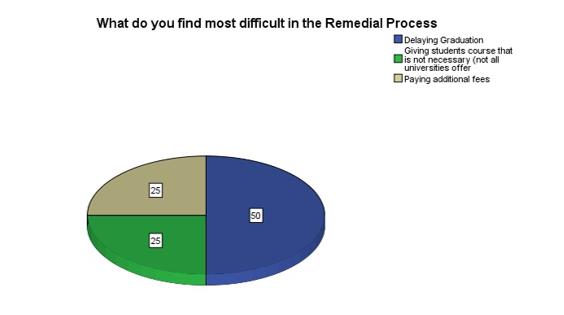

Figures 1 and 2 above show that a large majority of students who have undergone remediation are unaware of its value and are therefore do not know why they would need it. In these circumstances, they would not work to achieve the outcomes of the program. This then means that the fundamental resistance of the students towards remediation may be based on their ignorance of its value in their educational progress and experience.

When they have clear impressions of remediation, students resist it because they see remedial programs as duplicative and lengthening their college years unnecessarily. On entry to a university, quite often, the students aim to complete the degree program and to go to work or to graduate school. Their progress toward graduation is therefore very important to them. When they get on a remedial program, they feel that they are slowing down on their progress towards graduation. This is because remedial courses are non-credit and therefore do not count towards the requirements for graduation. Students are often in denial and will not want their friends to know they are in the remedial class. They therefore do not endeavor to adjust themselves in order to achieve the learning outcomes that the remedial course seeks to achieve. Many students do not understand the concept of preparedness for post-secondary education and will therefore not trust the results of the instruments used to determine their preparedness. Since they may have met the required grades for admission into the university, they will have difficulty understanding why they need to take a placement test or why they should be placed in a remedial class when their scores in the national examinations qualify them for automatic admission into the mainstream degree programs. They may point to reasonable grades they got in the subjects in which remediation is required and dismiss any requirement of them to undergo intervention. Jennlee3741 has identified the very needy student, the middle of the road student, and those who think they do not need any remedial classes as the three typical categories of students who often find themselves in the remedial class.

Because the content of the remedial program is normally below their level at the time, the underprepared students get to know that they are learning content and using material meant for lower levels. For example, the remedial writing or composition class might use textbooks or materials recommended for primary or secondary schools. This will humiliate the students in the remedial class and convince them that the university is trying to portray them as lacking intelligence. Because of the attitudes of many people, including their friends who did not need to be in the program, underprepared students struggle with the thought that they are perceived as intellectually deficient. They may therefore not want their friends to know that they are in remedial class.

Parents/ Sponsors

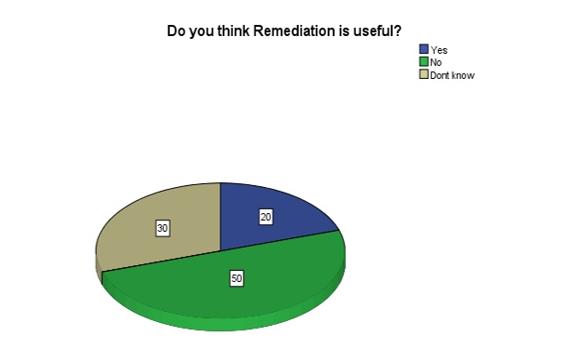

Parents or sponsors are the stakeholders in the remedial education who pay the fees that support the program. As observed earlier,their financial support of the program is dependent on the value they see in the program. The survey sought to establish their thoughts about remediation and their willingness to pay for it.

Would you like your child/sponsee to take remedial classes?

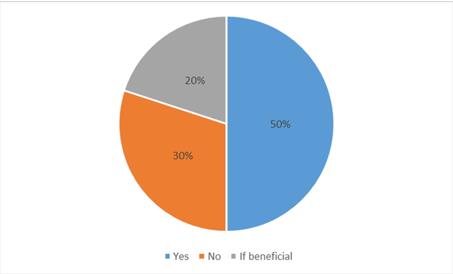

Figures 3,4, and 5 show the attitudes of sponsors or parents to remedial education. While figure 5 shows that half the sample of sponsors or parents appreciate the value of remediation and would like their sponsees or dependants to go through it, close to a quarter of the sample would only allow their sponsees or dependants to enroll in remediation if there was a guarantee that it would benefit them. The parents/guardians’ preference for remediation appears better than that of students. Figure 4 identifies the delay in graduation of students as the biggest concern for parents and sponsors while paying additional fees and the sense that remedial courses are not offered by all universities (hence not necessary) as equal but of lesser concern to the stakeholders. Figure 3 shows that a majority of parents/sponsors (80 percent) would prefer to enroll their sponsees or guardians to universities that do not offer remediation, with the belief that their progress towards graduation would be accelerated without remediation.

The survey shows that both students and their sponsors do not have a universal appreciation of the value of remediation as an opportunity for underprepared students to strengthen their skills for university education. Being unaware of the completion rates for students who do not take remediation, they are therefore unlikely to recognize the risks students who are underprepared take going into university education without remediation.

Other Stakeholders

Other stakeholders in remedial education include teachers, universities, tax payers and the government. In terms of the implementation of remediation, teachers probably come through as the most important.

Teachers involved in remediation resist it because of the professional stigma attached to teaching in such programs where they are often considered as not highly qualified by their colleagues. The universities exacerbate this problem by assigning the junior faculty to teach the remedial classes. In universities, instructors assigned to teach remedial programs also feel they are not part of the critical core of their departments since remedial programs are often located in pre-university sections or units and are not considered part of full university programs. Quite often, the teacher of the remedial class does not take responsibility for the low proficiency of his or her students and passes the buck in what Ponessa (1996) calls the “chain of blame” – a phrase used to refer to the cyclic tendency to shift responsibility for low proficiency by the universities to high schools, the high schools to the middle schools and the middle schools to the elementary schools. Many teachers in remedial classes may also not know whether they need diagnostic teaching or mere re-teaching.

Critics have questioned whether remediation removes the incentive for students to adequately prepare while in high school. The availability of remedial education at postsecondary level may remove the responsibility for proper preparation of high school graduates from their high school teachers. They will feel comfortable to let some skills training filter to college level because they know that remedial interventions will address them.

For the teacher, the remedial class has students who are poor in the skills required to undertake college-level work, students who need a lot of attention in the skills in which they are deficient. Many teachers think they should only teach top students because it is easier and more prestigious to teach such students. Without the right attitude, many teachers feel that they are teaching academically and/or intellectually-challenged students. They get desperate and may come to the conclusion that remediation is a waste of time.

There is a pressing need to work within the educational systems to help students achieve the required standards of preparedness for college-level education. This may be done in a way that precludes remedial education through more focused preparation in high school. This can only be done successfully by specifying and working on the skills that students need for college-level education. This inevitably requires cooperation between teachers at secondary education levels and those at college level. Comprehensive curricula may also need to be designed that take into account the progression students need between secondary and post-secondary levels.

However, it cannot be denied that no matter what measures are taken, some students will still need remediation. This may not only be required for fresh graduates coming from secondary schools but also adults who are either displaced from the workforce or those who find need to return to college to gain skills for career advancement. Whatever the need, such people will require remedial courses to refresh their skills. Helping all students successfully pass remedial and college-level courses can significantly improve their chances for success and increase college completion rates. Remedial education is therefore crucial for opening up access to university education for many students who would otherwise be locked out because of under preparedness. The compelling benefits of university education to students, their families and the government make remedial education a key empowering facility for underprepared students.

Benefits of College Education

The benefits of university education cannot be overemphasized. In spite of heavy financial costs, it is attractive because of “the prospect of wider opportunities and a higher standard of living which leads families to save in advance, sacrifice current consumption opportunities, and go into debt in order to enable their children to continue their education after high school” (Baum & Payea, 2005, p.5). Higher education is strongly associated with higher earnings and a comfortable life among the middle class. These combine with other benefits to the individual and the state to make university education a worthwhile investment. Governments therefore endeavor to invest large amounts of money to finance higher education by providing facilities, equipment and instructional resources and personnel, as well as financial aid to thousands of students who would otherwise not be able to afford it.

Countries struggling with high youth unemployment like Kenya with the startling demographic of 78% of her population below the age of 34 (Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, 2012; Maina, 2011; United Nations Development Program, 2012) and a figure of approximately 750,000 young people annually joining the labor market (Muthee, 2010) with only about 25% of them getting absorbed into the formal job market (Government of Kenya, 2007) need to expand access to university education. University education will empower graduates with usable skills that do not merely prepare them for formal employment but also entrepreneurship. This way, the country would get increased tax revenue from an empowered skilled public who would then go on to earn higher incomes, spend and save more which would improve the economy. It is the dream of every student graduating from high school to join the university. Unfortunately, a very large number of students do not meet the threshold for university admissions. Remedial education would be a great channel for enabling those unable to meet the threshold requirements to access university education.

University education will also ensure a more peaceful and law abiding citizenry. In the words of Barnet (n.d.) citing Saxon and Boylan (n.d.) “educated individuals are less likely to impose costs to society associated with imprisonment or warfare dependency”.

Apart from the mere feeling of accomplishment associated with getting to the top of the education ladder, students love the trappings of university education because of the status and career success it guarantees them. The benefits of college education cannot be overemphasized. According to College Board (2006) many people have a general sense that higher levels of education are associated with higher earnings and “… college is a prerequisite for a comfortable middle-class lifestyle” (p.5). It adds that college educated citizens contribute more to the public treasury and to the social wellbeing of the wider society in many significant ways. These would be benefits lost to society if secondary school graduates were denied entry into colleges or were to drop out due to under-preparedness. Remedial education therefore refurbishes students for admission into and successful graduation from college.

Hartel et al. (1994) enumerate many benefits of university education to individuals. Among these are the social mobility, professional or occupational competence, and status. It also ensures improves the individual’s communication, analytical and reasoning skills among others.

Conclusions and Implications

Remedial education is bedeviled by many issues. Such issues run from its cost from the position of the sponsor of the student, the institution and the government, its value to the student, the institution and the government in the face of competing priorities, and operational difficulties including instruments that are used to measure preparedness for it. Superficially, it would be easy to dismiss remedial education but a glance at the value of the access it gives underprepared students to university education and its global benefits means that every individual and institution tasked with its implementation needs to prepare to ensure its success. There are obviously issues that need to be addressed which include the snowballing number of students emerging from secondary schools underprepared for college-level work, the need to streamline the requirements of college work so that they may be addressed throughout the education system, the standardization of the test instruments that determine a student’s preparedness, and attitudes that attend to being part of the remedial process. It is therefore the contention of this paper that remedial education is a critical channel for access to university education for those who emerge from secondary education underprepared for college work.

Acknowledgements

The author(s) declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

Alliance for Excellent Education (2011) Saving Now and Saving Later: How High School Reform can reduce the Nation’s Wasted Remediation Dollars, Issue Brief, May 2011, http://www.ncacinc.com/sites/default/files/media/research/SavingNowSavingLaterRemediation.pdf, Retrieved, May 21, 2016.

Bailey, T. (2009), Challenge and Opportunity: Rethinking the Role and Function of Developmental Education in Community Colleges, New Directions for Community Colleges, 145, 11 – 30. DOI:

Barnett, E. (n.d.) Costs of Remediation, University of Illinois at Urbana – Champaign.

Baum, S., & Payea, K. (2005) Education Pays 2004: The Benefits of Higher Education for Individuals and Society, Trends in Higher Education Series, College Board.

Bettinger, E. P., & Long, B. T. (2008) Addressing the Needs of Under-Prepared Students in Higher Education: Does College Remediation Work? Journal of Human Resources, 44(3), 736 -771. DOI:

Calcagno, J. C., & Long, B. T. (2008) The Impact of Post-secondary Remediation using a regression discontinuity approach: Addressing endogenous sorting and noncompliance (NCPR Working Paper) New York: National Center for Postsecondary Research. DOI:

Gitonga, K. W. (2014). Navigating the Transition from College to Work: A study of Baccalaureate Graduates of a Private University in Kenya, Unpublished Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, Illinois.

Government of Kenya. (2007). Office of the vice president and ministry of state for youth affairs: Strategic plan 2007-2012. Nairobi, Kenya: Government of Kenya.

Hartel, W. C., Schwartz, S. W., Blume, S. D., & Gardner, J. N. (1994) Ready for the Real World, Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing Company.

Haycock, K., & Huang, S. (2001) Youth at the crossroads: Facing High school and beyond. [Electronic version] Thinking K-16, (5). 1.

Ignash, J. M. (Ed) Implementing effective policies for remedial and developmental education, New Directions For Community Colleges, 100, 73-80.

Jacobs, J. (2012). States Push Remedial Education to Community Colleges, US News and World Report, Education, January 13, 2012, http://www.usnews.com/education/best-colleges/articles/2012/01/13/states-push-remedial-education-to-community-colleges, retrieved, February 8, 2016.

Jennlee 3741, http://hubpages.com/hub/Teaching_in_Remedial_Classroom 72, retrieved April 23, 2012.

Kenya National Bureau of Statistics. (2012). Kenya facts and figures 2012. http://knbs.or.ke/downloads/pdf/Kenyafacts2012.pdf

Maina, R. W. (2011). Determinants of entrepreneurial intentions among Kenyan college graduates. KCA Journal of Business Management, 3(2), 2071-2162. DOI:

Manzo, K. K. (1996) Math, English Standards in California. Education Week, November 27.

Muthee, M. W. (2010). Hitting the target, missing the point: Youth policies and programmes in Kenya. Washington, DC: Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars.

Nasser, R. N., & Goff-Kfouri, C. A (2008), Assessment of the English Remedial Programme at a Private University in Lebanon. Mediterranean Journal of Educational Studies, 13(1), 85-100.

Ohio Board of Regents (2001) Ohio Colleges and Universities 2001: Profile of Student Outcomes, Experiences and Campus Measures. Columbus, O.H; Ohio Board of Regents

Onditi, T. L. S. (2013) The Impact of Remedial English on the Improvement of English Proficiency: The case of the United States International University – Africa, Procedia- Social and behavioral Sciences 152, 1178 – 1188. DOI:

Phipps, R. (1998) College Remediation: What is, What it costs, What’s at stake. Washington, D.C,: Institute for Higher Education Policy.

Ponessa, J. (1996) Chain of blame. Education Week, May 22, 29 – 33.

Sandham, J. L. (1998) Massachusetts plan would make districts pay for remediation. Education Week, February 18, 18.

Saxon, D. P., & Boylan, H. R. (n.d.) Research and issues regarding the cost of remedial education in higher education. National Center for Development Education, Retrieved March 24, 2016.

United Nations Development Program (2012) Global youth development forum on inclusive governance, http://www.ke.undp.org/index.php/news/2012/03/global-youth-leadership-forum-on-inclusive-governance, retrieved April 21, 2016.

Weissman, J., Bulakowski, C., & Jumisko, M. K. (1997). Using Research to evaluate developmental education programs and policies. In J. M. Ignash (Ed.) Implementing effective policies for remedial and developmental education, New Directions For Community Colleges: No 100 (pp. 73-80). San Francisco: Josey-Bass. DOI:

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.