Comparing Information from Focus-group Interviews with that Obtained by Surveys in an ESL Environment

Abstract

A great deal has been said about the strengths and weaknesses of the qualitative strategy of focus-group meetings but there has been insufficient illustration with empirical data. Focus groups are an expensive strategy, especially in an English-second-language (ESL) environment where translation is required as well as transcription. Because almost all focus groups in at The Chinese University of Hong Kong are conducted in Chinese, our aim was to ascertain what additional value (if any) was provided by focus groups when compared with surveys. We reviewed the views collected in six focus-group meetings with findings from surveys in six cases, where similar questions were asked with the two evaluation strategies to similar groups of students. We found that focus-group meetings provided the researchers with in-depth information of pertinent issues that enriched the survey data; in the paper, examples of ‘extension’, ‘elaboration’ and ‘consolidation’ of topics are explored. However, the opinions collected through focus groups may be questionable in terms of their generalizability because of a complex set of discussion dynamics. We will maintain our current practice of using both focus groups and surveys and triangulating the data.

Keywords:

Introduction

1.1. Focus-group interviews as an important data-collection strategy

The objective of focus-group interviews is to get high-quality data in a social context. Typical arrangements include a small group of four to twelve people, a trained moderator, a duration of one to two hours, a list of selected topics for discussion, and a non-threatening environment that encourages group interaction (Bloor, Frankland, Thomas, & Robson, 2001; Wilson, 1997).

Common characteristics of focus-group interviews are nicely summarized by Patton (2002, 1987):

- participants are typically a relatively homogeneous group of people;

- participants are asked by the interviewers to reflect on specific questions of interest;

- participants hear each other’s responses and can make additional comments and

- consensus is not required.

The focus group has received increasing attention since the 1970s, although the technique can be dated back to the work of Merton and Kendall (1946) and his collaborators in social science studies. Focus-group interviews are conducted, with a variety of styles and formats, in different disciplines including education (Vaughn, Schumm, & Sinagub, 1996), sociology (Folch-Lyon & Trost, 1981) and social sciences (Berg, 2007).

There are two very different approaches to the use of the method. One approach is to view the method as an additional strategy for a study together with other evaluation instruments. Manfredi, Lacey, Warnecke and Balch (1997, p. 798) stated that a research design with mixed instruments, for example focus-group interviews and surveys, “if used correctly, [provides] complementary perspectives”. Focus-group interviews can play a number of roles in supporting the triangulation of results using multiple evaluation strategies; Wilson’s (1997, p. 214) list of these roles is:

- as a prelude to a larger quantitative study, viz. to identify the language used by informants in order to frame a questionnaire;

- in conjunction with a quantitative project to deepen/ broaden the researcher’s understanding;

- to assist researchers in understanding previous data collected by quantitative methods; or

- in conjunction with other qualitative methods, e.g. in-depth interviews.

Another approach, however, is to view focus-group interviews as a stand-alone evaluation tool. Focus groups are generally more costly – in terms of time as well as human resources – than surveys (Hughes & DuMont 1993). Considerable effort is needed to transcribe, code, and analyze focus-group data. It is even more resource-intensive in the case of English-second-language (ESL) settings where translation of the transcript is often required as well. This, indeed, was the key reason for conducting the study reported in this paper.

Some benefits for the use of stand-alone focus-group interviews have been recorded in the literature. Hughes and DuMont (1993, p. 777) argued that the method is particularly useful in the understanding and framing of problems and issues in culturally anchored research, although they note that “focus-group samples are often small and non-representative, allowing for in-depth description of phenomena but not for generalization to a larger population”. Robinson (1999) suggested that the method has the potential of acquiring more information in the exploration of sensitive subjects such as health. Morgan (1996, p. 139) also noted that it is good for “investigating complex behaviours and motivations”.

A requirement for successful focus-group interviews (either as a stand-alone strategy or in conjunction with other evaluation tools) is that participants must feel comfortable in expressing and rethinking their views in the light of others’ responses. Bender and Ewbank, (1994, p. 65) suggested that the main advantage of the method lies in the group dynamics special to the context: “participants who discuss, debate or clarify one another’s given reasons are considerably more likely to be concerned with the validity of their answers than with providing the interviewer with socially correct (and possible invalid) responses”. It is important to note that the cumulative responses from focus groups involve a very complex set of dynamics that involve co-construction of meaning (Wilkinson, 1998; Warr, 2005). In addition, there are have cultural nuances and standard strategies and interpretations from literature in the West may not reflect the nuances that subtly operate in an Asian context.

Interactive focus-group interviews have the potential to solicit a large amount and range of data, allow extreme views to be considered but not to dominate, and ensure unambiguous opinions as the facilitator has the chance to seek clarifications (Robinson, 1999). On the whole, focus-group interviews allow detailed exploration of a topic with more evidence about the reasons behind opinions through capturing participants’ examples, stories and feelings. Morgan (1996, p. 137) acknowledged that there is a contrast between “the depth that focus groups provided” and the “breadth that surveys offered”.

Saint-Germain, Bassford and Montano (1993, p. 364) praised the capability of the method to reveal hidden information which might otherwise be difficult to unearth and unpack: “with survey data, the researcher may often by surprised at the findings, but along expected dimensions. With focus-group data, however, the researcher is continually surprised along unexpected dimensions”.

1.2. Uncertainties about the value of focus-group interviews

However, many of the positive claims made above are not supported by empirical evidence and, indeed, many of the claims have been challenged. For example, groups may actually “inhibit individual articulation” (Stycos, 1981, p. 451). Also, there are “audience effects” resulting in “fewer idiosyncratic thoughts, more moderation in judgments, more common associations, more cautiousness, and a general taking into account of the anticipated reaction of the audience” (Stycos, 1981, p. 451). There are also concerns about the possibility of “false consensus” and “group polarization” effects – “people in groups have a tendency either to move toward a consensus or to shift toward unrepresentative extremes” (Lunt & Livingstone, 1996, p. 93).

In our context in Hong Kong we need to acknowledge the Chinese concept of ‘face’ in collecting opinion data. Some of the issues relating to concerns about being on public (or even semi-private) record reflect the concept of face. The positive side of face is care for the other, a gentle politeness (Brown & Levinson, 1987). The negative side of face is avoidance of conflict at all costs and extreme unwillingness to take risks. A long-term psychologist in Hong Kong, Bond (1991) described the constraints of face in these terms:

Given the importance of having face and of being related to those who do, there is a plethora of relationship politics in Chinese culture. … the use of external status symbols, sensitivity to insult, … the sedulous avoidance of criticism, all abound, and require considerable readjustment for someone used to organizing social life by impersonal rules, frankness, and greater equality (p. 59).

Other obvious weaknesses include the limited number of questions that can be covered (Robinson, 1999); matters of confidentiality between participants; and, as mentioned above, the costliness of the strategy.

Of some concern are the literature reports that suggest that opinions solicited from focus-group interviews are similar to those collected through other research means (especially those from surveys). For example, Ward, Bertrand and Brown (1991, p. 269) reported that “focus groups yielded results similar to those obtained from surveys in the three studies reported herein”. In addition, there are reports that indicate apparent inconsistencies between data from a range of sources (e.g. Amos, Currie, & Hunt, 1991; Backett & Alexander, 1991). While the cause of these differences may be argued by some as relating to weaknesses in the actual focus-group interviews, the differences could also relate to issues in survey design (Morgan, 1996).

More investigation into the value of costly focus groups, especially about whether they offer unique data sources, appears to be warranted.

This study reviewed data collected through focus-group meetings and compared them with survey feedback. However, we did not intend to ‘prove’ which strategy – survey or focus-group interview – is a better tool to use in evaluation. The main purpose is to revisit the main benefits of focus-group interviews with empirical evidence. The study has been designed to answer the question: ‘What kinds of additional information do focus-group interviews provide that might justify the associated costs?’

Methodology

We transcribed and translated conversations recorded in six focus-group interviews, and collated the opinions collected from surveys administered in the same contexts.

The focus-group meetings were all about one hour long in which one or two facilitators conversed with a group which varied in size between six and 14 students. The meetings were associated with two quite distinct projects.

The first three meetings were evaluations of a two-year enrichment programme for secondary school students gifted in Science who attended workshops and completed projects at The Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK). The goal of the project was to offer young gifted students greater opportunities to explore and develop their higher-order thinking skills, creativity and personal–social competencies. The project employed a number of evaluation strategies to reflect upon the achievement of the objectives at various stages of the project. These included a number of surveys and focus groups. The three focus-group meetings that were transcribed for this study were held at the end of the whole programme (2008) in which three groups of students (the Mathematics, Physics and Biology streams respectively) discussed various aspects of the programme. At the same time, a survey, covering similar topics, was administered to a larger group of students.

The second set of focus-group meetings came from a study with groups of Years 1 and 2 students in the Faculty of Law at CUHK. In 2006–07, the Law programme was established at CUHK. As part of its overall evaluation of this new programme, the Faculty wanted a focused evaluation of the skill-based courses such as Legal Research, Writing, and Information Literacy. Students were asked to fill in a questionnaire on the design, relevance and applicability of the courses. In order to give students an opportunity to elaborate on their views, students were also invited to attend focus-group meetings in April 2008. Three of these meetings were transcribed. Two of the meetings involved Year 1 students and one involved Year 2 students. At the same time, a similar survey was also administered to the whole cohort of students in both years asking them similar questions to those covered in the meetings. Table 1 summarizes the number of students surveyed and interviewed in each of the six individual cases.

The student evaluations of educational experiences reported in this paper focus on matters that are considered very important in Hong Kong. Education is highly valued and access to prestigious programmes and institutions is very competitive. Students entering both the ‘gifted’ Science programme and the Law programme were carefully selected, and having evidence of success (or otherwise) of these initiatives is considered to be very important. The decision to include both surveys and focus groups was taken in order to ensure greater certainty about the findings. The interview and survey questions did not relate to taboo matters (quite the reverse) and were not unusually complex (see Robinson, 1999; Morgan, 1996, cited earlier). However, Hong Kong students can be quite constrained in discussions of even quite straight-forward topics. Overall, as the stakes were high for both the Science project and the newly established Faculty of Law, the investment was considered worthwhile.

A research assistant with experience in doing transcription for qualitative educational research transcribed all the conversations recorded in the focus-group interviews. Transcription was done to a level where pauses and co-occurring utterances were represented. As most meetings were conducted in Cantonese, another process was done to translate the transcribed file into English. Note that the English of the quotes in this paper can be described as ‘Hong Kong English’ as this is the way students would speak in English. The six transcriptions and translations occupied about one month of a research assistant’s time. Converting that into monetary terms, the transcription work roughly cost us HKD20,000 (approximately USD3000). In addition, of course, the researchers spent time and effort in preparation for the meetings, the meetings themselves, and in writing post-meeting summaries.

For the surveys, student helpers with suitable qualifications were employed to input the paper-based surveys into computer-readable formats. Feedback to open-ended questions was fully typed out. Chinese feedback was translated into English. Student helpers are paid only USD6.50 per hour and so such work is very inexpensive.

Semantic coding was the method employed to identify themes from the raw data (De Weer et al., 2006). In semantic coding, ideas are classified into a variety of themes through careful content analysis. Semantic coding schemes used in other studies were referred to in the process; such as those Krueger (1998) used when working on the types of probing techniques by facilitators, and those used by Henri (1992) when analyzing responses of participants. However, while reference was made to other coding schemes, we were cognizant of the uniqueness of our context and so maintained some elements (such as the discussion themes and their coding categories) of a grounded approach (Glaser & Strauss, 1968) in the study. Thus, the themes were based mainly on our own analysis of the raw data. The coding strategies and resultant themes were reached through consensus, made in an iterative fashion after a number of discussions in the research team. The coded ideas were analyzed to highlight similarities and differences. For the differences, further explorations were made to classify and structure the differences until generalizations were reached. Investigators’ meetings were held to discuss interpretations and generalizations.

For example, the following piece of dialogue was thematically coded as discussing a topic about ‘course content and method’. The student elaborated on the course experience through highlighting one event called ‘wolf and sheep’ (coded as elaboration with example). The student also expressed how s/he felt about the event (coded as opinions).

[S3]: ‘We have an experiment on ‘wolf and sheep’ and see how do the hunting habit affect the ecological environment (). What I learn from this helps my understanding on biology ()’. [Biology]

The following conservation was thematically coded as ‘course perspective and development’. The students expressed their opinions on the curriculum designs (coded as opinions). They also mentioned facts of the course (coded as stating facts) and some confusion about the course designs were clarified (coded as clarify or redefine facts).

[S2]: ‘That’s good enough to have legal research but that is quite compact. I learned this after talking with the senior students.’ ()

[S7]: ‘There are just four lessons for this.’ ()

[Facilitator]: ‘In fact, it’s the same. There were four lessons for legal research in the past.’ ()

[S2]: ‘Really? It seems that they were having more than that.’ (code: clarify or redefine facts) [Law]

The conservation below was thematically about ‘suggestions for course improvement’. The student mentioned some facts (coded as stating facts) about the course and seemed to have hinted for some changes (coded as hinted opinions).

They also clarified some of the facts (coded as clarify or redefine facts).

[S1]: ‘We haven’t got any test or exam in order to demonstrate how to write the ratio.’ () ()

[S2]: ‘Right. We just got a theory.’ (code: stating facts) (code: underlying opinions)

[S7]: ‘No, we did have to write a ratio. ()

[S4]: ‘We did. We got to write a ratio in the exam.’ ()

[S2]: ‘Maybe I forgot it…’ () [Law]

Findings

3.1. Extension

One obvious finding when we compared the two sets of feedback collected from the two types of instruments was that focus-group meetings more easily led to unplanned digressions in the discussion topics and/or unexpected responses. This we summed as the tendency of focus-group meetings to lead to ‘extension’ of ideas.

Before each focus-group meeting, the facilitators had a set of planned questions to cover in the meeting. However, the facilitators were also reminded that these planned questions were to guide the discussion but not to restrict the discussion. The exact order of the questions, and on-the-spot decisions made during the interview about whether some questions had become redundant, were recognized as being very flexible processes. The main guiding principle for the facilitator was enabling a smooth flow as much as possible without too much interference while, at the same time, keeping the discussion on track (Carey & Smith, 1992, 1994; Sim, 1998). Sim (1998, p. 347) also suggested that “a balance needs to be struck in terms of the prominence and involvement of the moderator in the proceedings of a focus group”.

A diverse range of topics was thus an interesting characteristic of our focus-group meetings. We analyzed the themes covered in both focus-group meetings and surveys in terms of whether unexpected extensions took place. Very often we found that the extended topics or comments were not actually off-topic diversions from the discussion plan but enabled the priorities about various factors involved in any issue to be fine-tuned. Table 2 illustrates one such difference in our focus-group and survey pairs.

The table shows the diversity of discussion topics covered in the Biology focus-group meeting compared with the content covered in the corresponding survey administered to the students. We can see that, while students briefly mentioned some additional points in the open-ended section of the survey, the amount of discussion and the richness of the discussion were more detailed in the focus-group meeting. Apart from the expected discussions on course content and processes, for example, the students also talked about other matters that seemed to be important to them: the teachers’ teaching styles and attitudes, their self-learning, time management, logistical issues such as transportation, and also their original expectations of the course. They were also able to provide many examples from their experiences in the course to explain the points.

Similar extensions of topics were also apparent in the other focus-group meetings. For example, the students in the Mathematics group explored the fact that the teacher might not have a full understanding of the students’ prior knowledge:

[S3]: ‘I think the professor is unclear about what we have or haven’t learned. For example, differentiation … we are all form 4 students. As differentiation is a topic for F.5 students, we may not have an idea of it but the professor had assumed prior knowledge we had.’

[S8]: ‘Right, the level is an issue.’

[S5]: ‘The teacher assumed that we all have prior knowledge on differentiation.’ [Mathematics]

The students were able to initiate and give insightful overall summative remarks to their learning experience. Some examples are:

[S11]: ‘The focus seems to be on the score but not for learning.’ [Physics] [S3]: ‘In fact, we did not have good learning atmosphere for these few tutorials. The professor talked on her own and we did not listen to her. Nobody dared to ask questions. For the 45 minutes, it was very boring. Nevertheless, that professor talked very slowly.’ [Law]

[S8]: ‘What we learned in this program just required hard memorization.’ [Law]

[S1]: ‘Despite the concern of money, it is wasting our time and credits. It took 3 hours every week for the ELT [English] course and that is a 3-credit course.’ ‘Is it a kind of measure to fulfill the university requirements or with some other reasons? To me, it seems that such arrangement is for fulfillment of university requirements.’ [Law]

Extension also happened in the range of answers participants tend to give. While many of the survey questions are laid out in multiple-choice format with the expectation that most of the respondents’ responses fall within a limited range of preset answers, the focus-group discussions are more likely to lead to answers that extend beyond the expected range of answers. This can supplement the data obtained from the survey. Table 3 shows the answers received in two questions asked in focus-group meetings as compared with the answers shown on the survey in similar questions asked in the survey. Although there was space in the survey that allowed the respondents to indicate answers that were not covered by the existing choices, few additions were received. We can see that focus-group discussions led the researchers to document a much richer range of responses.

We can compare the answers to the question about the acquisition of the knowledge of Common Law in the Law focus-group meeting and survey. The answers to this question in the survey tended to be simple answers such as ‘yes’ or ‘no’. Even the related comments recorded in the open-ended section of the survey seemed to echoed the same answer: ‘It is useful …’. The answers collected in the focus-group discussions were much richer in this respect. Apart from giving the researchers a similar general tone that they were positive about the teaching of Common Law (perhaps because of the chance to interact with each other in the meeting, or the fact that they spent more time thinking about this question in the focus-group context), they carried on to further refine their answers by stressing a component (Common Law in Hong Kong) of the course was less impressive than the rest. Similarly, the answer given by students below is a much richer version of a simple ‘yes’ to the question about the level of difficulty of the teaching content.

[S3]: ‘A little bit difficult but so far so good. If it is easy, I don’t think we need to spend extra time for this.’

[S2]: ‘That’s fine. No good to make it too easy. We won’t be benefitted from this course if it is too easy for us. Slightly difficult course can force us to think harder.’ [Physics]

The extensions to open-ended questions, such as ‘how to further improve’ the course or workshops, were obvious. More suggestions were often collected in focus-group meetings and often these comments were carefully elaborated, compared to the brief notes by students on a survey.

[S1]: ‘For statistics, I think it is possible to get some ideas from the approach of the UST [University of Science and Technology] team … (then carried on to describe the approach of the UST team)’ [Mathematics]

[S4]: ‘I think it had better to fill the information gap. Good enough to have a brief explanation … (then discussions of what additional information was needed)’ [Biology]

The number of the above two main types of extensions as observed in each of our focus group meetings is summarized on Table 4.

However, sometimes the extensions were genuine distractions. There were extensions that led discussions further away from the main interest of the researchers. For example, students in the science enrichment programme brought up issues about the logistics of the workshops and program arrangement:

[S8]: ‘We want more breaks.’ [Biology]

[S11]: ‘It is sufficient enough to have 10-15 minutes for break.’ [Biology] [S9]: ‘Not really. That’s great if we can take leave from school to join these

sessions.’ [Mathematics]

[S1]: ‘If we are able to install Matlab at home …’ [Mathematics]

[S7]: ‘I would like to ask a question where the $2000 we paid has gone.’ [Mathematics]

[S8]: ‘But the best is the supply of refreshments.’ [Mathematics]

[S12]: ‘In fact, we are tired during the school days. How come it requires us to get up early on Saturday morning?’ [Physics]

[S1]: ‘Very nice. It is because there are refreshments provided.’ [Physics]

The extended topic was not of key interest to the researchers. The facilitators needed to be very conscious about where the diversions were leading to and redirect the attention of the students back to the main topics of the discussion when necessary. This involves techniques or strategies a facilitator should use but are not discussed here.

3.2. Elaboration

Another major difference between the feedback in focus-group meetings and that from the survey forms is the rich elaboration of points possible through the conversational interactions.

Elaboration refers to further explanations of the firstgiven in response to a question. For example, participants may further providefor doing something or having a certain type of opinion, anto further illustrate the points, and/or more details to the answer (such as a situation where an opinion applies but not in another situation) serving toor eventhe answer.can also be made in addition to the opinions given.

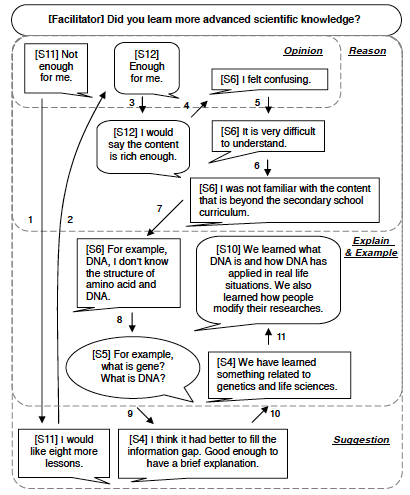

Figure 1 illustrates the elaboration that took place surrounding the answers to the question ‘’ in one focus-group meeting of the science enrichment programme. Rather than simply answering whether the students felt satisfied about the knowledge they had learned, they also talked about the reasons (arrows 3–7). Further, they provided some examples of the learning experiences to illustrate the situation. They also reflected to some extent about what their learning needs for the future might be (arrows 8–11).

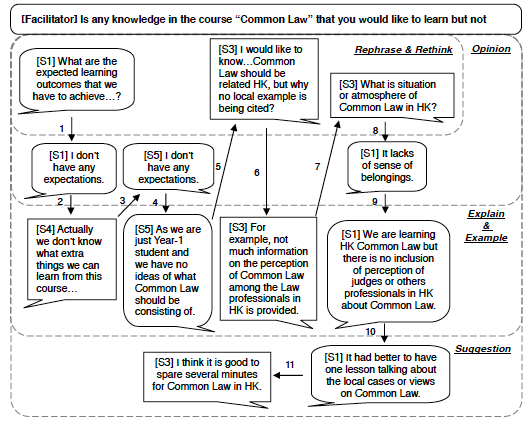

Figure 2 shows the analysis of another chain of interactions surrounding the question in one of the Law meetings: ‘Is there any knowledge in the course ‘Common Law’ that you would like to learn but is not covered’. After giving the first replies to the question, the students continued to talk about the reasons they held these views and also some examples illustrating the learning experiences in the course (arrows 1–5). In addition, students would rethink standpoint because of the conversation and then restate their opinions and reasons with different examples provided (arrows 6–9). Like the previous example (Figure 1), they also reflected on the process of learning knowledge and suggested what could be improved (arrows 10–11).

Table 5 summarizes the occurrence of the opinions recorded and their following elaborations in each focus-group meeting. Expressing opinions was a major type of elaboration found, followed by providing examples and reasons. Other than these, the participants also refined/ rephrased their comments to better illustrate ideas.

We thus see that interactions contributions to rich information in a focus-group meeting. Such elaboration is not likely to be found in survey data as there are no interactions and discussion processes involved. Our focus-group data thus demonstrate processes of “social enactment” (Halkier, 2010).

With a survey, respondents normally stop after they have answered the quantitative questions. Even though there are spaces for the respondents to write down open-ended feedback, the feedback comments are often short and come in broken pieces. The linkage between one piece of information and another is often missing and researchers find it hard to relate causes, reasons or examples together.

3.3. Consolidation

The collaborative elaboration of ideas in the focus-group discussions allows different points of view to be consolidated. The viewpoints after consolidation tend to be more accepted as everyone involved in the process should have carefully considered multiple points of views before arriving at their final views. The consolidated views may not necessarily be very different from the original views the participants held. However, very often the consolidated views are more refined views; sometimes there are minor adjustments to accommodate views of others; sometimes there are more major compromises after one group becomes more aware of the ideas of another group; and sometimes two seemingly opposite views can be found to be both useful, only that one of the views refers to specific situations in certain contexts while the other view addresses other situations. Below are some quotes from the discussions that show various types of consolidation.

Compared with this, opinions collected via surveys are not consolidated views. We may know how the majority of the students feel about a certain issue but we cannot tell whether the view can sustain criticism. In discussions less representative views, seemingly held by only a few individuals, can often influence many others if they are given the opportunity to explain and interact.

3.4. Case of agree

[Facilitator]: ‘What do you think about the level of difficulty for this particular course? Is it too difficult or not?’

[S1]: ‘A little bit difficult but so far so good. If it is easy, I don’t think we need to spend extra time for this.’

[S2]: ‘That’s fine. No good to make it too easy. We won’t be benefitted from this course if it is too easy for us. Slightly difficult course can force us to think harder.’

Case of compromise

[S1]: ‘We haven’t got any test or exam in order to demonstrate how to write the ratio.’

[S2]: ‘Right. We just got a theory.’ [S7]: ‘No, we did have to write a ratio.’

[S4]: ‘We did. We got to write a ratio in the exam.’ [S2]: ‘Maybe I forgot it…

Case of adjustment

[S4]: ‘We had written memorandum.’

[S6]: ‘…yes, but I don’t think we could learn.’ [S1]: ‘Just once, or twice…’

[S6]: ‘Right, we have no solid experience of writing memorandum at all.’

Case of opposite view

[S7]: ‘The ELT course mentioned and provided assistance in writing memorandum.’

[S5]: ‘But it is not the objective of ELT.’

Table 6 illustrates the number of occurrences of consolidations identified.

Consolidation of ideas may be an ideal situation in which changes of opinions in focus-group meetings appear. However, as Carey (1995) warned, changes of an individual’s opinions in a focus-group meeting may not always be a result of rational reasons. She suggested that ‘conforming’ and ‘censoring’ of ideas can occur. In the former situation, the participants tend to express opinions that more readily conform to public expectations or the perceived expectations of the facilitators; in an Asian context this would be seen as saving face. In the latter situation, participants might be affected by the more aggressive and outspoken members in the discussion group and are too intimidated to express views against them; in an Asian context overt aggression is rare but more articulate group members can have undue influence. Unfortunately, it is very difficult to distinguish, either during the actual discussions or through reading the discussion transcripts afterwards, the distinction between lasting consolidation of ideas and transient changes of ideas caused by interpersonal reasons.

Discussion and Conclusion

We have obtained empirical data to explain a number of characteristics of the comments collected in six focus-group meetings. Three processes were found to be prominent in the focus-group discussions: extension, elaboration and consolidation.

Extensions are points where the flow of the discussion or the content of the discussion itself goes beyond the plan or expectations of the facilitators. Extension can be beneficial or detrimental to the overall research purpose depending on how far participants become diverted from the main topic of the research study. Appropriate extensions enrich researchers’ understanding of an issue. They also reflect the importance of a topic to the participants, and indicate when the priorities differ from the researchers’ expectations.

Elaborations enrich participants’ first answers to a question by supplying additional information such as that related to the ‘why’, ‘what’, ‘how’, ‘where’, etc., of the first comments. Elaborations also build linkage (such as cause-and-effect relations) between the various comments and facts. Such knowledge is essential for researchers to obtain an in-depth understand of any phenomenon. This is a major characteristic that sets the focus-group strategy apart from survey research.

Consolidation of ideas results when the participants change or refine their points of view after rational and careful consideration of multiple viewpoints. The interactive nature of focus-group meetings provides the environment required for idea exchange and then consolidation to take place. Consolidated ideas seem to be more meaningful data for researchers. However, we noted that not all changes of ideas by an individual are rational. ‘Censoring’ and ‘conforming’ may influence the participants’ views through incorrectly inserting peer-group pressure. In our context in Hong Kong, issues of ‘face’ can strongly influence the process of consolidation and consensus.

A facilitator can support genuine idea consolidation through maintaining a relaxed and open discussion environment. Facilitators should emphasize their neutral standpoint and see their role as facilitating and supporting balanced discussion – for example, by ensuring appropriate sharing of time between the group members as much as possible.

Despite the challenges of ensuring good facilitation of focus-group meetings, there is a clear potential for obtaining rich information through this evaluation strategy. Useful information is collected using the focus-group strategy that cannot be easily solicited through using less costly surveys.

Human factors can easily influence the quality of the feedback collected in focus groups. This reinforces a common principle of qualitative research in the social sciences – that of triangulation (Cohen & Manion, 1986; Denzin, 1978) where an integration of multiple research or evaluation strategies is used. If researchers are more aware of the strengths and weaknesses of each of the evaluation strategies they use, their research designs are likely to be more robust. Multiple sources of data, often including both quantitative and qualitative data, collected through multiple methods are needed for understanding complex multi-faceted issues such as appropriate educational design for courses supporting the development of higher-order thinking skills.

Finally, our study strengthened our own awareness of the importance of facilitator strategies and interaction patterns, and has influenced the focus-group training we provide for our new research staff at CUHK.

We will maintain our current practice of using both focus groups and surveys and triangulating the data.

Acknowledgements

Funding support from the University Grants Committee in Hong Kong and from the Quality Education Fund of the Hong Kong Education Bureau is gratefully acknowledged, as is the collegial contributions of colleagues and students in the Faculties of Science and Law at The Chinese University of Hong Kong.

References

Amos, A., Currie, C., & Hunt, S. (1991). A comparison of the consistency of self-report behavioural change within a study ample – Postal versus home interviews. Health Education Research, 6, 479–486.

Backett, K. C., & Alexander, H. (1991). Talking to young children about health: Methods and findings. Health Education Journal, 50, 34–38.

Bender, D. E., Ewbank, D. (1994). The focus group as a tool for health research: Issues in design and analysis. Health Transition Review, 4(1), 63–79.

Berg, B. L. (2007). Qualitative research methods for the social sciences. Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Bloor, M., Frankland, J., Thomas, M., & Robson, K. (2001). Focus groups in social research. London: Sage.

Bond, M. H. (1991). Beyond the Chinese face. Insights from psychology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Brown, P., & Levinson, S. C. (1987). Politeness: Some universals in language usage. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Carey, M. A. (1995). Comment: Concerns in the analysis of focus group data. Qualitative Health Research, 5(4), 487–495.

Carey, M. A., & Smith, M. W. (1992). Enhancement of validity through qualitative approaches. Evaluation & The Health Professions, 15(5), 107–114.

Carey, M. A., & Smith, M. W. (1994). Capturing the group effect in focus groups: A special concern in analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 4(1), 123–127.

Cohen, L., & Manion, L. (1986). Research methods in education. London: Croom Helm.

De Weer, B., Schellens, T., Valcke, M., & Van Keer, H., 2006. Content analysis schemes to analyze transcripts of online asynchronous discussion groups: A review. Computers & Education, 46, 6–28.

Denzin, N. (1978). Sociological methods: A sourcebook. New York: McGraw Hill. Folch-Lyon, E., & Trost, J. F. (1981). Conducting focus group sessions. Studies in Family Planning, 12(12), 443–449.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1968). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

Halkier, B. (2010). Focus group as social enactments: Integrating interactions and content in the analysis of focus group data. Qualitative research, 10(1), 71–89.

Henri, F. (1992). Collaborative learning through computer conferencing. London: Springer-Verlag.

Hughes, D., & DuMont, K. (1993). Using focus groups to facilitate culturally anchored research. Culturally Anchored Methodology, 21(6), 775–806.

Krueger, R. A., (1998). Developing questions for focus groups. California: SEGA Publications.

Lunt, P., & Livingstone, S. (1996). Rethinking the focus group in media and communications research. Journal of Communication, 46(2), 79–98.

Manfredi, C., Lacey, L., Warnecke, R., & Balch, G. (1997). Method effects in survey and focus group findings: Understanding smoking cessation in low-SES African American women. Health Education and Behavior, 24(6), 786–800.

Merton, R. K., & Kendall, P. L. (1946). The focused interview. The American Journal of Sociology, 51(6), 541–557.

Morgan, D. L. (1996). Focus groups. Annual Review of Sociology, 22(1), 129–152. Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research and evaluation methods (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Patton, M. Q. (1987). Depth interviewing. In M. Q. Patton (Ed.). How to use qualitative methods in evaluation. California: SAGE Publications.

Robinson, N., (1999). The use of focus group methodology – with selected examples from sexual health research. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 29(4), 905–913.

Saint-Germsin, M. A., Bassford, T. L., & Montano, G. (1993). Surveys and focus groups in health research with older Hispanic Women. Qualitative Health Research, 3(3), 341–367.

Sim, J., (1998). Collecting and analyzing qualitative data: Issues raised by the focus group. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 28(2), 345–352.

Stycos, J. M. (1981). A critique of focus group survey research: The Machismo case. Studies in Family Planning, 12(12), 450–456.

Vaughn, S., Schumm, J. S., & Sinagub, J. (1996). Focus group interviews in education and psychology. California: SAGE Publications.

Ward, V. M., Bertrand, J. T., & Brown, L. F. (1991). The comparability of focus group and survey results. Evaluation Review, 15(2), 266–283.

Warr, D. J. (2005). ‘It was fun…but we don’t usually talk about these things’: Analyzing sociable interaction in focus groups, Qualitative Inquiry, 11(2), 200–25.

Wilkinson, S. (1998). Focus group methodology: A review. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 1(3), 181–203.

Wilson, V. (1997). Focus groups: A useful qualitative method for educational research? British Educational Research Journal, 23(2), 209–224.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.