Teachers Support of Students’ Social-Emotional and Self-Management Skills Using a Solution-Focused Skillful-Class Method

Abstract

Increasing importance is being attached to support students’ learning of social-emotional and self-management skills as they may experience all kinds of difficulties and problems at school. How can teachers support students to learn useful skills to overcome these problems? The purpose of this study is to assess the effectiveness of the Skillful-Class method, which teachers can use in their classrooms to support students learn social-emotional and self-management skills in a supportive and collaborative learning environment. A Skillful-Class project was conducted in 22 Finnish and 18 Chinese primary school classes. Data was collected by pre- and post-questionnaires from autumn 2018 – spring 2019. Qualitative data was collected using a post questionnaire with open-ended questions, interviews, and discussions on webpages, which were reviewed by content analysis. There is clear evidence showing that students’ skills improved significantly; further, the relationships among students, teachers, and parents also improved. The students became more supportive of and collaborative with each other. The teachers’ responses also show that their work became easier at school when students learned many social-emotional and self-management skills. Based on these findings, we can conclude that the Skillful-Class method is an effective tool for teachers to help students learn skills. Further, it improves the collaboration among teachers, students, and parents, and builds a supportive and collaborative learning community.

Keywords: Solution-focused approach, Skillful-Class, learning skills, learning community

Introduction

The world is changing dramatically because of new technologies and new demands at work, and schools are facing a major crisis in trying to respond. Additionally, managing global challenges, such as climate change, requires schools and education systems to emphasize not only high-quality knowledge but also social-emotional, self-management, and behavioral skills that will lead to fostering good social relationships and help students to become active citizens. Countries and educational organizations have been promoting the learning of 21st century skills at school (OECD, 2013; Lee & Tan, 2018; Niemi & Jia, 2016; Statistics Finland, 2016). There is thus, an increasing need for teachers to help their students to learn many social-emotional and self-management skills in the school environment. Moreover, how students and teachers work together in learning skills is also extremely important in improving the relationships among students, teachers, and parents to create a supportive and collaborative learning community in schools.

It is quite common in many schools that students have certain behavior and social-emotional problems, such as disturbing others, ignoring their homework, losing their tempers when things do not go their way, becoming afraid of talking in public, etc. The purpose of this study is to assess the effect of the Skillful-Class method, which teachers can use in their classrooms to help students learn social-emotional and self-management skills in a supportive and collaborative classroom learning environment.

Theoretical framework of the study

This study is based on the solution-focused approach (SFA) that was developed by Insoo Kim Berg and Steve de Shazer in 1980s (DeJong & Berg, 2002; de Shazer, 1985, 1988). SFA has been widely used in practice (Ajmal & Rees, 2001; Alexander & Sked, 2010; Morgan, 2016; Cepukiene, Pakrosnis, & Ulinskaite, 2018). It is a goal-directed, collaborative approach to psychotherapeutic change (Pichot, & Dolan, 2003; Lutz, 2013). The key idea behind SFA is looking into the future, or, rather, at the desired outcomes of the preferred future. It also aims to discover what the strengths and resources can be used to realize that preferred future (George, Iveson, & Ratner, 1999). The SFA also focuses on building supportive relationships (DeJong & Berg, 2002).

There are many principles and assumptions of the SFA, which have been listed by many researchers (Quick, 2008; Sklare, Sabella, & Petrosko, 2003; Lipchik, 2011; Nicholas, 2014). From the perspective of schools, the most important aspects of SFA is to help students to learn skills concerning how they can manage their own lives. It helps them to (1) focus on goals, (2) discover strengths and resources, and (3) perform many small actions for desired changes. This means that skills must be specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART), criteria which are often used in setting goals. SMART is often used to provide criteria to guide the setting of objectives, in, for example, project management, employee-performance management, and personal development (Doran, 1981; Bogue, 2018).

Kim, Kelly, and Franklin (2008) have stated that the advantages of SFA in a school setting are its strengths-based approach, client centered vision, and concrete actions in which small changes matter. Strengths-based means that people have strengths which are active in helping when managing life situations. Client-centered means clients can determine their own goals and make decisions about how and where they wish to make changes in their lives. And “small changes” means that, by focusing on making small changes that help, the children see themselves as more capable of making other and larger changes in their lives (Kim, Kelly, & Franklin, 2008).

The intervention in this study is called the Skillful-Class Method, developed from the SFA Kids’ Skill Method (KSM), which was created in the 1990s by Dr. Ben Furman and two other teachers (Furman, 2004, 2010) to help children overcome social-emotional and behavior problems by encouraging children to learn skills. Furman developed the Skillful-Class method with his experience using the KSM in over 30 countries across decades. Many teachers have used the KSM to help students having problems at school. Teachers asked how, with large class sizes and limited time for individual instruction, they might help more students. Therefore, Dr. Ben Furman and his colleague Maiju Ahola developed the Skillful-Class method for teachers to help all students to learn social-emotional and self-management skills. They asked teachers to describe common problems at school, and turned these problems into skills for the students to learn. The most needed social-emotional and self-management skills in primary schools were identified by primary school teachers in Finland. They are listed in in Table 1.

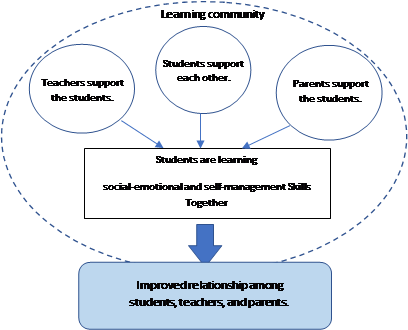

The Skillful-Class method is based on the SFA. This means that (1) the focus is on learning the skill instead of talking about the problem, and (2) the key player is the student her or himself. He or she decides what skill to learn, and the emphasis is on students’ strengths and previously learned skills. Finally, (3) small steps and progresses are big motivation factors. Additionally, when students learn skills together, they support teachers and learn from each other, which leads to a supportive and collaborative learning community.

The Skillful-Class method has a strong emphasis on social community and how students can learn from each other. In that sense, it has a close relationship to the Social Culture Theory and Learning Community in which Russian psychologist Lev Vygotsky (1896–1934) argues that social interaction precedes development (Vygotsky, 1980, 1978). Vygotsky’s theories stress the fundamental role of social interaction in the development of cognition (Vygotsky, 1978), as he believed strongly that community plays a central role in the process of “making meaning”. Vygotsky places considerable importance on social factors contributing to cognitive development. According to Vygotsky, the environment in which children grow up will influence how they think and what they think about. He focuses on the connections between people and the sociocultural context in which they act in and interact with shared experiences (Crawford, 1996), believing that young children are curious and actively involved in their own learning and the discovery and development of new understandings or schema.

Table 1 reveals that the purpose of the Skillful-Class method is to help students in primary schools learn many basic social-emotional and self-management skills, which are useful and beneficial for the students as well as for the teachers’ work. The Skillful-Class method includes two phases. First, the students and teacher will discuss and vote for one skill to learn from the first six collective skills. The whole class will learn the same skill together, so that the students understand and learn how to learn a skill. Normally, it takes about two weeks for the students to learn the collective skill in the first phase. Second, each student will choose his or her individual skill to learn from the above-mentioned 22 skills. It is acceptable for several students to choose the same skill and form a group to learn that skill together. It takes about three to four weeks for the students to learn their individual skills in second phase.

Each participating class will receive one set of skill cards. The skill cards consist of the name of the skill, a picture of the skill, and a detailed explanation of the skill. The teacher will discuss each skill with the whole class, so that all students understand the meaning of the skill and how to perform it. The skill cards can be put up on the classroom walls. The figure 1 below illustrates what a skill card looks like.

The teachers’ roles are those of facilitators, supporters, coaches, offering scaffolding for the students while learning the skills. Parents are informed by the school teachers that the children are learning these skills at school. The parents can also support their children. The teachers also inform the school principal, who is asked to support them.

Before the students start to learn the skills, the students and teachers (1) discuss the benefits of learning the selected skills, (2) demonstrate or roleplay what the skills look like, and (3) decide on the behavior that shows the students have learned the skills and (4) how to celebrate their success in learning the skill/s. After all the students have learned the skills at the end of the project, the principal will hand out a framed certificate with the Skillful-Class logo to the class. Then the whole class will celebrate their success in learning the skills together.

Research problem and objectives

The purpose of this study is to assess the effectiveness of Skillful-Class method in helping students learn socio-emotional and self-management skills together and how this method improves the positive relationships among students, teachers, and parents. The design of the study is illustrated in Figure 2.

Our research questions are:

- Can the solution-focused Skillful-Class method effectively support students to learn socio-emotional and self-management skills?

- What are the impacts on, or changes to, the relationships among students, teachers, and parents when students are learning social-emotional and self-management skills?

Research methodology

This project was implemented in Finland and China at the same time, 2018 autumn – 2019 spring. This project was designed for primary school teachers to help students learn the social-emotional and self-management skills described in Table 1. The project invitation was sent to the school teachers who showed interest in August 2018, and participation was voluntary. 22 Finnish primary school classes with 20 Finnish teachers, and 18 Chinese primary school classes with 18 Chinese teachers participated in the project.

The 22 Finnish teachers are from 4 different cities and 13 different primary schools. Some of these teachers had used Dr. Ben Furman’s KSM before, and were interested in doing more. Some teachers heard about this project from their colleagues and became interested. Most are from capital areas (Helsinki, Espoo, and Vantaa), except two from Ikaalinen. The participating Chinese teachers had used the KSM or heard about it. They were very eager to join the project to improve their classes. They are from the following city and provinces: Beijing city, Hebei province, Guizhou province, Liaoning province, and the Zhejiang province. All participating teachers from both Finland and China are female (see table 2).

Research context

Before the project started, the teachers from Finland came to a central meeting place in Helsinki and were given one day training by Dr. Ben Furman and the main researcher for this project on how to implement the Skillful-Class Method. The Skillful-Class Method instruction and 28 skill cards were given to all the teachers. The students and teacher would study the skill cards together to understand what the skills mean and how to demonstrate them. The skill cards are placed on the wall of the classroom when the students are learning the skills as a reminder, and so the students may look at the cards in case they forget what the skills mean. A webpage for Finnish teachers was set up. All participating Finnish teachers, Dr. Ben Furman and his team, and the main researcher (who speaks English, Chinese, and Finnish) had access to the webpage, so that the Finnish teachers could ask questions and gain support from Dr. Furman and the researcher during the project. The teachers could also share their experiences and get ideas from each other via webpage interaction.

The teachers in China are from several areas, making it logistically difficult to get all the teachers together in one place. The training for Chinese teachers was thus conducted in the Chinese language over the online Chinese social media tool WeChat by the Kids’ Skill company in China and the project’s main researcher. There were three two-hour training sessions. A WeChat group was created with all participating Chinese teachers, two staff from the Kids’ Skill company in China, and the main researcher. The teachers could ask questions, offer support, and share information in this Skillful-Class project group.

In this study, the Skillful-Class project was implemented in the following two phases:

Phase 1: All students in the same class were learning one similar skill together. The skill was selected and decided upon by the whole class.

Phase 2: After all the students had learned the collectively selected skill, each student chose his or her own skill to learn. Several students could choose the same individual skill and learn it together.

First, the teacher introduced the project to the class and showed them the skill cards. The students and teacher discussed what each skill meant. All students in the class assessed how good they were with the six collective skills on a scale from one to five. The teacher then showed the students the class’ average score for each. Then, the whole class voted on which skill to learn together. After the class had chosen the collective skill, the teacher discussed with the students the following aspects, which are adapted from Furman’s KSM (Furman, 2004, 2010):

- What are the benefits of learning this skill?

- Why do we all believe that the students can learn the skill by discovering together their strengths, resources, and past successes?

- How do we define the skill? Ask the students to show and demonstrate the skill, and record or photograph it with a mobile phone.

- How can the students support each other in learning the skill, and how can their parents, grandparents, or other teachers be their supporters? What do the students want their supporters to do when they do a great job in practicing their skill? In case the students forget the skill, how do the students want their supporters to remind them?

- How do students plan to celebrate when the whole class has learned the skill? What shows that the students have learned the skill?

From these discussions, the students see the benefits of learning the skill they have chosen, believe they can do it, and know how. Most importantly, they know that they are learning the skill together: they will receive support from each other and from teachers, parents, and so on. A collaborative and supportive learning community is formed, with the goal of learning the skill.

The whole process of discussion is built on

- students’ participation and autonomy

- the benefits of learning the skill

- students’ confidence, strengths, resources, and past successes

- collaboration and support in the learning community

- future success

The aim is that the students develop powerful motivation and confidence for learning the skill. The method also encourages the students’ participation and strengthens their feeling of choice, decision, and inner motivation. The goal of the discussion is to: (1) discover and create motivation for learning, (2) increase students’ confidence in learning the skills, (3) clearly show how to perform the skills, and (4) build a supportive learning community.

Data gathering

The study design includes both quantitative and qualitative research methods. Since the Skillful-Class method is designed for younger students in primary schools to help them develop social-emotional and self-management skills in the beginning of their schooling, the studied students are from grades one to four. The students are considered too young to provide reliable data. Therefore, we mainly focused on the teachers’ perceptions. Before the teachers started to implement Skillful-Class method, all participating teachers from Finland and China were asked to fill out the pre-questionnaire. After the whole project was completed, all the teachers were asked to fill out the post-questionnaire, which includes not only quantitative data questions but also open-ended, qualitative data questions.

Qualitative data consisted also of web discussions, WeChat discussions, and a few teacher interviews. Students’ parents were informed about the school project and that students would be learning the skills, but data was not gathered from them.

The instruments

All the instruments (Skillful-Class Instruction, Skills Cards, Questionnaires) were created in English first, then translated to Finnish and Chinese. The main researcher is fluent in English, Chinese, and Finnish. The English versions were checked and doublechecked by at least five experts in the field, and the Chinese and Finnish versions were each checked by three native speakers. The 28 skill cards each had a picture to illustrate the meaning of the skill, the name of the skill, and a detailed description of the skills. Before producing the skills cards, we asked three young students to look at them to determine whether they understood the skills on the card, and modifications were made if needed. The teachers were asked to assess the students’ six skills and the relationships among students, teachers, and parents before and after the project. The teachers’ questionnaire is illustrated in Tables 3 and 4. Open-ended questions were asked in the end.

Open-ended questions to be answered by teachers about the changes after the project are the following:

- What kind of changes have you perceived on students’ behavior and class atmosphere after the Skillful-Class project?

- What kind of changes have you perceived on your work and life after the Skillful-Class project?

- What kind of changes have you perceived on the relationship between you and the students’ parents after the Skillful-Class project?

- Any additional comments about the Skillful-Class Method?

Data analysis

Both quantitative and qualitative data were extracted in this study. We used content analysis for the qualitative data. Content analysis is a research method for making valid inferences from data relevant to its context; the purpose is to provide knowledge, new insights, a representation of facts, and a practical guide for action (Krippendorff, 1980). The challenge can be that each researcher interprets the data according to her or his subjective perspective (Sandelowski, 1995). Creswell, Hanson, Clark Plano and Morales (2007) say that qualitative researchers approach their topics with a specific worldview, which contains a set of beliefs or assumptions. This study involved Finnish-, Chinese-, and English-speaking researchers, and we wanted to be aware of our cultural backgrounds while we aimed to understand what happens in the Finnish and Chinese classrooms. Levitt (2015) argues that qualitative research requires one to adopt an interpretative rather than procedure-driven method of working. Qualitative research relies on the identification of the “subjective interpretation of data”, which enables meaningful data interpretation (Levitt, 2015).

In this study, the quantitative data was analyzed using descriptive statistics, such as mean values and standard deviation. We performed the summative variable reliability test for the items relating to students’ skills and the relationships among students, teachers, and parents. The scales’ reliability was deemed to be very good. The Cronbach alpha of the Student Skill scale’s pre-test and post-test was .78 and .76 respectively both of which are in the acceptable range. The Cronbach alpha for the pre-test of the Relationship among Students, Teachers, and Parents scales’ was .81 while that of the post-test was .89, both of which are also in the acceptable range.

Research findings

The research questions focus on how well the students learned certain defined social-emotional and self-management skills and what changes happened in the relationships among students, teachers, and parents with the Skillful-Class intervention. Table 5 shows the teachers’ perceptions of the changes on the students’ skills and relationship. Teachers assessed that in Finnish classrooms, students’ social-emotional and self-management skills increased from mean value of 3.17 to 3.80 (p = .000). They assessed also that the relationship among students, teachers, and parents improved from mean value of 3.67 to 4.10 (p =.000). In Chinese classrooms, students’ social-emotional and self-management skills increased from mean value of 3.44 to 4.42 (p = .000). And the relationship among students, teachers, and parents also improved from mean value of 4.04 to 4.60 (p = .000). All changes between pre and post measurements were statistically significant.

What follows are quotes from teachers based on the open-ended questionnaire and from interviews. The following quotes illustrate the teachers’ perceptions on the changes in students’ skills. After each quote, there is a code in brackets, which indicates for each teacher an identification code with country (Fi= Finland, Ch=China) and a number. Several teachers stated that the students had better self-management skills (including the behaviour skills):

Children have become better at verbalizing and speaking with good manners. (Fi5)

The students have learned conversational skills and have become better at listening to each other. (Fi14)

Several teachers stated that the students have better social emotional skills, including self-confidence, collaboration, and supportiveness:

The following quotes illustrate the teachers’ perception on the changes in the atmosphere of the class and the relationships among students, teachers, and parents:

Additionally, there are some surprising changes in students’ learning, attitudes, and mindsets which were noticed by several teachers:

There were also interesting and relevant changes to the teachers’ attitudes and mindsets:

Four teachers also stated that their work become easier after students learned many skills:

Some parents also gave some feedback to the teachers about this project:

When we asked the participating teachers what other comments they had about the Skillful-Class Method, the majority expressed their interest in continuing to use it or the SFA in their classes. They said that learning skills instead of talking about problems was the better approach. One teacher, Fi19, said a couple of students lied about the progress of the class’ collective skill because they were so eager to achieve the target. She suggested that next time she would progress more slowly and devote enough time to learning the class collective skill to make sure that all students master the skill before moving to the individual skill. Two teachers, Fi5 and Fi14, suggested that they could include some additional skills, categorize the skills in a way better suited to them, and make their own list of skill cards. Two teachers, Chi6 and Chi9, suggested that the parents may also need some training to be more involved in supporting their children. One teacher, Fi3, said that the skill cards and the instruction were useful, but it would be better if there was no number on the skill cards. She plans to remove some skill cards for next time.

Discussion and conclusion

The aim of this study was to find out how the Skillful-Class intervention method helps students learn self-management and social-emotional skills at school and what the impacts of this intervention are on the relationships among students, teachers, and parents. With both quantitative and qualitative evidence, the current study confirms earlier research findings (DeJong & Berg, 2002; Morgan, 2016; Cepukiene et al., 2018) that SFA can create positive changes. Cepukiene and Pakrosnis’ (2011) stated that SFBT can be especially useful for altering behavior. The effectiveness of SFA and SFBT have been studied by many researchers (Corcoran & Pillai, 2007; Franklin, Treper, Gringerich, & McCollum, 2012; Gingerich, Kim, Stams, & Macdonald, 2012; Gingerich & Peterson, 2013; Kim & Frankin, 2009; Stobie, Boyle, & Woolfson, 2005) with a focus on family problems and child behavior in the context of both school and family. Bond, Woods, Humphrey, Symes and Green (2013) have done a comprehensive study of SFBT with families and children. They provide preliminary evidence that SFBT can improve children’s internal social-emotional and external behavioral problems both in school and with their families. The Skillful-Class intervention method is based on SFA and SFBT. The present study provides significant results based on quantitative data and rich evidence from qualitative data that the students in this study learned many self-management and social-emotional skills. In our study, we identified the positive changes in the relationships among students, teachers, and parents, which is the basis for positive improvements. Additionally, there is also evidence showing that students’ and teachers’ mindsets and attitudes have changed. They became more positive, solution-focused, and goal-oriented. Some teachers also stated that their work became easier. Finally, we found similar results in both Finnish and Chinese schools, which have different cultural backgrounds and contexts which proves that the Skillful-Class intervention method is successful even in different socio-cultural contexts.

In conclusion, based on the findings, the solution-focused Skillful-Class method provides an effective pedagogical tool for teachers when supporting students’ development towards self-management and social-emotional skills. Further, this method improves the relationships among students, teachers, and parents. After the students learned many useful skills, teachers’ work become easier and the classroom atmosphere improved. Students’ and teachers’ mindsets and attitudes are also shifting to become positive and goal-focused instead of problem-focused.

Limitations and future research

This is the first research project for the SFA Skillful-Class intervention method. Our samples are limited to 22 Finnish classes and 18 Chinese classes. For future studies, the sample size can be increased. Additional self-management and social-emotion skills can be suggested and differentiated for different aged students. For students over 10 years old, simple questionnaire data and interviews can be used to obtain students’ perceptions on this method. It can also be carried out in different countries and in different contexts.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their thanks for the support from Dr. Ben Furman and Maiju Ahola from the Helsinki Brief Therapy Institute and from Julia Li and Wei Wei from “I Can Do It” (Beijing) Management Consulting Ltd. for their support in the project implementation and data collection.

References

Ajmal, Y., & Rees, I. (Eds). (2001). Solutions in schools: Creative applications of SF thinking with young people and adults. London: BT Press.

Alexander, S., & Sked, H. (2010). The development of solution focused multi-agency meetings in a psychological service. Educational Psychology in Practice, 26(3), 239-249.

Bogue, R. (2018). Use S.M.A.R.T. goals to launch management by objectives plan. TechRepublic. Retrieved from https://www.techrepublic.com/article/use-smart-goals-to-launch-management-by-objectives-plan/

Bond, C., Woods, K., Humphrey, N., Symes, W., & Green, L. (2013). Practitioner review: The effectiveness of solution focused brief therapy with children and families: A systematic and critical evaluation of the literature from 1990-2010. Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 54(7), 707-23.

Cepukiene, V., & Pakrosnis, R. (2011). The outcome of solution-focused brief therapy among foster care adolescents: The changes of behavior and perceived somatic and cognitive difficulties. Children and Youth Services Review, 33(6), 791-797.

Cepukiene, V., Pakrosnis, R., & Ulinskaite, G. (2018). Outcome of the solution-focused self-efficacy enhancement group intervention for adolescents in foster care setting. Children and Youth Services Review, 88, 81-87.

Corcoran, J., & Pillai, V. (2007). A review of the research on solution focused therapy. British Journal of Social Work, 39, 234-242.

Crawford, K. (1996). Vygotskian approaches in human development in the information era. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 31(1-2), 43-62.

Creswell, J. W., Hanson, W. E., Clark Plano, V. L., & Morales, A. (2007). Qualitative research designs: selection and implementation. The Counseling Psychologist, 35(2), 236-264.

DeJong, P., & Berg, I. K. (2002). Interviewing for solutions. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole.

De Shazer, S. (1985). Keys to solution in brief therapy. New York: Norton

De Shazer, S. (1988). Clues: investigating solutions in brief therapy. New York: Norton

Doran, G. T. (1981). There's a S.M.A.R.T. way to write management's goals and objectives. Management Review, 70(11), 35-36.

Franklin, C., Treper, T., Gringerich, W., & McCollum, E. (2012). Solution-focused brief therapy: A handbook of evidence-based practice. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Furman, B. (2004). Kids’ skills: Playful and practical solution-finding with children. Bendigo: Innovative Resources.

Furman, B. (2010). Kids’ skills in action: Stories of playful and practical solution-finding with children. Bendigo: Innovative Resources.

Furman, B. (2018). Instruction for teachers using Skillful-Class intervention methods in primary schools. Helsinki: Helsinki Brief Therapy Institute.

George, E., Iveson, C., & Ratner, H. (1999). Problem to solution: Brief therapy with individuals and families. London: Brief Therapy Press.

Gingerich, W. J., Kim, J. S., Stams, G. J. J. M., & Macdonald, A. J. (2012). Solution-focused brief therapy outcome research. In C. Franklin, T. S. Trepper, W. J. Gingerich, & E. E. McCollum (Eds.), Solution-focused brief therapy: A handbook of evidence-based practice (pp. 95-111). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Gingerich, W. J., & Peterson, L. T. (2013). Effectiveness of solution-focused brief therapy: A systematic qualitative review of controlled outcome studies. Research on Social Work Practice, 23(3), 266-283.

Kim, J. S., Kelly, M. S., & Franklin, C. (2008). Solution-focused brief therapy in schools. Location: New York. Oxford University Press.

Kim, J. S., & Frankin, C. (2009). Solution focused brief therapy in schools: A review of the outcome literature. Children and Youth Services Review, 31, 464-470.

Krippendorff, K. (1980). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Newbury Park: Sage Publications.

Lee, W. O., & Tan, P-L. (2018). The new roles for twenty-first-century teachers: Facilitator, knowledge broker, and pedagogical weaver. In H. Niemi, A. Toom, A. Kallioniemi, & J. Lavonen (Eds.), The teacher’s role in the changing globalizing world: Resources and challenges related to the professional work of teaching (pp. 11-31). Leiden: Brill Sense.

Levitt, H. M. (2015). Interpretation-driven guidelines for designing and evaluating grounded theory research: a constructivist-social justice approach. In O. C. G. Gelo, A. Pritz, & Rieken (Eds.), Psychotherapy research (pp. 455-483). Vienna: Springer.

Lipchik, E. (2011). Beyond technique in solution focused therapy: Working with emotions and the therapeutic relationship. New York: Guilford Press.

Lutz, A. B. (2013). Learning solution-focused therapy: An illustrated guide. Arlington, Virginia: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Morgan, G. (2016). Organizational change: A solution-focused approach. Educational Psychology in Practice, 32(2), 133-144.

Nicholas, A. (2014). Solution focused brief therapy with children who stutter. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 193(C), 209-216.

Niemi, H., & Jia, J. (2016). What are new ways to teach and learn in China and Finland? In H. Niemi & J. Jia (Eds.), New Ways to Teach and Learn in China and Finland. Crossing Boundaries with Technology (pp. 9 -18). Franfurt, Publisher: Peter Lang GmbH.

OECD. (2013). Innovative Learning Environments, Educational Research and Innovation. Paris: OECD- Publishing.

Pichot, T., & Dolan, Y. (2003). Solution-focused brief therapy. New York: Haworth.

Quick, E. K. (2008). Doing what works in brief therapy: A strategic solution focused approach (2nd ed.). San Diego: Academic Press.

Sklare, G. B., Sabella, R. A., & Petrosko, J. M. (2003). A preliminary study of the effects of group solution-focused guided imagery on recurring individual problems. The Journal for Specialists in Group Work, 28(4), 370-381.

Sandelowski, M. (1995). Qualitative analysis: What it is and how to begin? Research in Nursing & Health, 18, 371-375.

Statistics Finland (2016). Finnish residents use the Internet more and more often. Retrieved from http://www.stat.fi/til/sutivi/2016/

Stobie, I., Boyle, J., & Woolfson, L. (2005). Solution-focused approaches in the practice of UK educational psychologists: A study of the nature of their application and evidence of their effectiveness. School Psychology International, 26, 5-28.

Vygotsky, L. (1978). Interaction between learning and development. Readings on the Development of Children, 23(3), 34-41.

Vygotsky, L. (1980). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. London: Harvard University Press.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.