The Impact Of Parental Feeding Practices On Their Children’s Appetitive Traits: A Study Among Children Aged 5-11 Years Old In Dubai Private Schools

Abstract

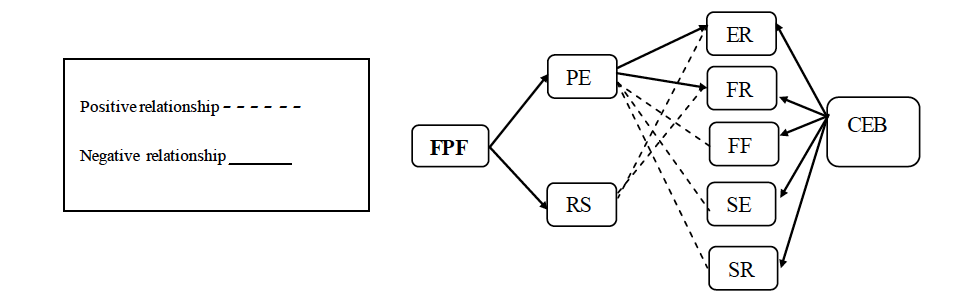

This study explores associations between parental feeding practices and children's appetitive traits, putting to test the hypotheses that a) parental “restriction” is associated with having a child with stronger food approach tendencies (food enjoyment (FE) and food over responsiveness (FR)), and b) parental pressure to eat is associated with having a child with food avoidance tendencies (satiety responsiveness (SR), slowness in eating (SE) and food fussiness (FF)). The participants, from 55 nationalities, targeting 1083 parents of 5- to 11-year-old children from 7 private schools in Dubai, UAE, who completed self- reported questionnaires over the 2011-2012 school year. The questionnaire has been a tailored amalgamation of CEBQ and CFQ in order to measure the children’s appetitive traits and parental feeding practices, respectively. The findings of this quantitative, descriptive, cross-sectional analysis confirmed the hypotheses in that “parental restriction” was positively associated with child food responsiveness (r, 0.183), and food enjoyment (r, 0.102). On the other hand, parental pressure to eat was positively associated with child satiety responsiveness (r, 0.265), slowness (r, 0.253), and fussiness (r, 0.174) and negatively with food enjoyment (r, -0.214) and food responsiveness (r, - 0.142). To conclude, as far as the figures depict, the parents controlling their children’s food intake would seemingly a reverse impact on their eating behaviour in the short term.

Keywords: Parental feeding practices, children eating behaviour

Introduction

Eating is one of the fundamental human needs throughout one’s life; and, as a result, it has a vital effect on people’s health. As Brown and Ogden (2004) argue, dietary habits gained in childhood persist through adulthood. Nowadays, children’s eating behaviours have changed drastically and turned into a predicament both for the parents and, at times, the children themselves. Children usually do not pay attention to their internal cues for hunger and satiety. Parents’ feeding practices have been a much neglected factor and usually the index finger has been pointed to children themselves, while recent studies reflect a twist towards the parents and their own feeding practices. Parents’ pivotal role in this field is clearly put by Birch (2006) where she says: “Parents can filter, buffer, and interpret macro-environmental influence on the children… Parental feeding practices as an effective role may determine the type of foods and portion sizes that children are offered, the frequency of eating occasions and the social contexts in which eating occurs”. She further argues that it may have substantial effects on the weight, growth, and development of their children in the early ages of their lives. In the same vein, Scaglioni, Salvioni, and Galimberti (2008) confirm that the major part of child’s food preferences and energy intake are developed in the family environment under the parent supervision. That is why the present study aims to find out the impact of parental feeding practices on their children's appetitive traits. “Pressure to eat” and “restriction” are two of direct strategies which are adopted by parents and have been investigated in this study as well. Parents exert pressure to ensure their children eat healthy food or maintain an adequate food intake. They employ restriction to limit the amount of food intake or prohibit from junk food consumption. Studies show that “Pressure to eat” is related to the children’s eating behaviour (Gregory, Paxton, & Brozovic, 2010). Avoidance of eating is the common response of children to this strategy. Children whose parents force them to eat may take longer to eat by keeping food in their mouth to avoid the next spoon. Drucker and his co-workers (1999) found this result in an experiment which examined duration of eating however, Iannotti and his colleagues in 1994 argued that pressure to eat is related to faster eating (Webber, Cooke, Hill, & Wardle, 2010). Besides, using this approach might cause rejection of a specific food (the one parents make themto eat) (Fisher & Birch, 1999). Other outcomes of this practice might be having picky eater children (Ventrura & Birch, 2008) which can manifest itself in poorer dietary quality during childhood (Campbell, Crawford, & Ball, 2006) and (Fisher, Mitchell, Smiciklas, & Birch, 2002) and less healthy food preferences (Carruth & Skinner, 2000), (Galloway, Fiorito, Lee, & Birch, 2005) and (Russel & Worsley, 2008). There is a longitudinal experiment in this field that shows the long-term effect of using this practice. In that experiment, 7 years old girls whose mothers regularly used pressure to make the meat as a feeding strategy became more picky at the age of 9 (Galloway, Fiorito, Lee, & Birch, 2005). Galloway, Fiorito, Francis, & Birch (2006) found that making children to eat would decrease their preferences and the amount of food taken during a meal time; they might also make negative comments about the target food. Many researchers believe that parental pressure to eat is positively related to fussy eating and food neo-phobia (rejection of new foods) as well (Galloway, Fiorito, Francis, & Birch, 2006)) and (Wardle, Carnell, & Cooke 2005). Moreover, “Pressure to eat” can impair child food interest (Gregory, Paxton, & Brozovic, 2010) and enjoyment (Galloway, Fiorito, Lee, & Birch 2005). According to a study, children who were less under pressure showed greater food enjoyment or responsiveness to external cues than their siblings who were pressured more (Webber, Cooke, Hill andWardle2010). “Pressure to eat” as a feeding practice, does not always appear in the form of force. Sometimes it emerges in the form of reinforcement, which includes praises and rewards. Among techniques that parents employ to increase the quality and the amount of their children’s intake, food reward is a very common instrument. For example: “if you eat some vegetables, then I would let you eat some cake (as a reward)”, but this trick does not always work. It may increase the child’s consumption of that food in the short time, but it will decrease the child’s preference for the target food in the long term while it raises the tendency toward the rewarded food in the child (Ventrura & Birch, 2008). Another issue in this regard is a kind of “conditioning” which is one of the learning methods being used. Batsell and Brown (1998) suggest that forcing children to eat may have negative effects on their eating habits since they may associate the food with the negative feeding experience they had (cognitive aversion) (Nordin, Broman, Garvill, & Nyroos, 2004). Moreover, in some instances, having a dreadful memory of one specific situation can generalize to other similar conditions; this means that if a child had a terrible experience towards a particular new food, he may feel the same when is exposed to any kind of new foods in the future (Gregory, Paxton, & Brozovic, 2010) and might lead the child to food neo-phobia. One of the harmful consequences of this feeding practice is teaching children to ignore their internal cues and eat beyond satiety. It can also lead the child to get higher energy intake at a meal and gain weight (Webber, Cooke, Hill, & Wardle, 2010), (Campbell, Crawford, & Ball, 2006; Fisher, Mitchell, Smiciklas, & Birch, 2002).

“Restriction” as a direct feeding strategy is very popular among parents; although parents apply this feeding practice to control their children’s eating, but it might backfire. In fact, children choose their approach toward eating in order to deal with their parents’ restriction feeding practice. In this survey, food responsiveness and food enjoyment have been studied accordingly.

Enhancing restriction would increase the child’s passion and preference toward some limited types of food. In an experiment, there were two groups of snacks, one freely accessible and the other with some limitations. When they were both freely available, children ate more of the restricted snacks in comparison with the unrestricted ones (Webber, Cooke, Hill, & Wardle, 2010) and (Fisher & Birch 1999). Attractiveness toward the restricted things in life is, in fact, in the nature of human being. Children are not an exception in this regard. So, children who do not have permission to access to some food, are made to be magnetized more to those. Hence, availability of the restricted items, make children out of control and even if they are not hungry, they still feel an attraction toward that type of food and mislead them to overconsumption. So, by this mechanism children will follow the external cues instead of their internal signals (Fisher & Birch, 1999) and (Birch, Fisher, & Davison, 2003). In fact, it causes children to eat in absence of hunger, which has been shown to be more common in girls than boys (Birch & Fisher, 2000). Another longitudinal study confirms this issue by examining it among a sample of 5 years old girls. When they get nine, girls whose mothers exert high levels of restriction showed more eating in absence of hunger in comparison with those whose mothers used lower levels of restriction (Birch, Fisher, & Davison 2003). In addition, Webber, Cooke, Hill, and Wardle (2010) explain that parental restriction and food responsiveness in children may have a positive link while they do not find the same relation with food enjoyment. Another outcome of this strategy might be “food neo-phobia” in children. One recent study which has been conducted on 85 mothers having 3-12 years old children shows that mothers whose children were diagnosed as high food neo-phobia, exerted more restriction as a feeding practice (Tan & Holub, 2012). Focus on the bidirectional relationship of parents-child feeding is of the utmost importance. It means that, this relations hip is not only influenced by parents’ feeding strategies on their children’s eating behaviour and habits but also children eating traits make parents to employ a particular feeding practice as well. Confirming this issue, some researchers found out parents whose children are fussy, picky, slow in eating, having less food enjoyment or any kinds of problematic eating behaviour, use “pressure” more during their children’s feeding, (Webber, Cooke, Hill, & Wardle, 2010; Ventrura & Birch, 2008) and (Farrow, Galloway, & Fraser, 2009). Furthermore, studies have shown that children, who were more food responsive, had mothers who were more likely to restrict their intake of unhealthy foods (Webber, Cooke, Hill, & Wardle, 2010).

Methods

Study Design

After receiving approval from the Islamic Azad University Research Committee of Dubai branch, the researcher was provided with an introduction letter for schools to be a part of the study. Seven schools were randomly chosen and they accepted sincerely to be part of this survey. During April and June 2012, schools received packets including 4000 nameless questionnaires. Participants were parents whose children were between 5 and 11years old attending in these seven schools. 1135 questionnaires returned to schools. 52 questionnaires were removed from the statistical investigation for bearing deficient information on a number of subscales; thus, there were only 1083 questionnaires included in the statistical analysis. Each questionnaire was supposed to be filled out by one of the parents concerning one particular child which inquired about that child’s eating traits and the parents’ feeding practices. These schools are scattered throughout different areas of Dubai and there is a wide ethnic diversity since Dubai is an international community. Data collecting lasted for almost one month (April to June).

Measures

Demographic Characteristics

The demographic part of this questionnaire included questions about the age, nationality, level of parent’s education along with the target child’s gender, age, position in the birth order and the number of siblings in the family.

Children’s Eating Behavior

The Children's Eating Behaviour Questionnaire (CEBQ) is an analytical pattern which used as a part of current study data accumulating instrument (Sleddens, Kremers, & Thijs 2008). From subscales of this questionnaire 5 factors have been drawn to be used in this study which includes two main aspects of child eating behaviour: “Approach toward eating” (Food responsiveness (FR), Enjoyment of food (EF)) and “Avoidance of eating” (Satiety responsiveness (SR), Slowness in eating (SE), Food fussiness, (FF)). 5 questions were assessing “Food Responsiveness” (e.g. , “If allowed to, my child would eat too much”), 4 questions that were measuring “Enjoyment of Food” (e.g., “My child loves food”), 5 questions were for “Satiety Responsiveness” (e.g., “My child gets full before his/her meal is finished”) , 4 questions were for “Slowness in Eating” (e.g., “My child takes more than 30 minutes to finish a meal”) and 6 questions were used for assessing “food fussiness” (e.g., “My child is difficult to please with meals”).Parents were asked to evaluate how frequently their children reveal particular eating- related behaviour on 5-point Likert scales ranging from“agree” (5) to “disagree” (1) through the current survey. The internal reliability values (Cronbach’s alpha coefficient) of each factor in this study are shown in table 1.

Parental Feeding Practices

The present study employed two subscales (pressure to eat and restriction) from CFQ (Child Feeding Questionnaire) to measure parental feeding practices (Birch, Fisher, Grimm-Thomas, Markey, Sawyer, & Johnson 2001). Pressure subscale consists of 4 questions (e.g., “If my child says ‘I’m not hungry’ I try to get him/her to eat anyway”) addressing parents’ tendency to pressure their children to eat more and the restriction subscale consists of 8 questions (e.g., “If I did not guide or regulate my child’s eating, he/she would eat too much of his/her favorite foods”) addressing parents’ tendency to restrict the amount and type of food for children. Totally 12 questions out of 31 from the original questionnaire have been used in this study. Participants responded on a 5-point scale ranging from “never” (1) to “always” (5). The internal reliability values (Cronbach’s alpha coefficient) of each factor in this study are shown in table 1.

Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis which were employed in this research are; “Chi squared Test”, “The Independent Sample T- Test”, “Tukey Test” and “MANOVA”. They were used to examine possible relationship between PFP (Parents feeding practice) and CEB (Child eating behaviour) as well as the frequency of parental feeding practices and children’s eating behaviours.

Results

Demographics

Data were obtained from self administered questionnaires, completed by 1083 parents of students’ age between 5-11years old and 27.1% response rate. Child demographic characteristics are shown in Table 2. Children’s demographic data shows that the mean age of the children was 4.8 years (SD: 0.8), facts and figures, show that half of the children (47.9%, n=519) were female, while almost 40% (40.3%, n=436) were male, however 11.8% (n=128) of parents didn’t mention their children’s gender. Parents mostly fill the questionnaires with regard to their first child (38.8%, n=417). Almost a quarter of these children (23.3%, n=252) were second child in their families. Mothers who participated in this study were between 25 and 55 years old; and the common age for mothers were between 31-40 years of age (70.9%, n=704). Information with regards to Mothers’ education shows 817(75.6%) out of 1083 mothers enjoyed their academic degrees (associate or higher). Asian mothers (84.49%, n=908) were the majority of the participants while Europe, Africa and America have almost same proportion (approximately 4%). The lowest percentage belongs to Australia which is less than one percent. The age range of the fathers was between 30 and 66. The majority of fathers (63.06%) were between 36 -45 years old. The educational trends for fathers and fathers’ nationality show a similar pattern as with mothers.

Descriptive Statistics for Children’s Appetites and Parental Feeding Practices

The descriptive statistics for all questions and the data on feeding practices were initially analyzed to confirm that the scales had adequate reliability for the present sample. The mean scores were as follows: The results show that all variables are well and above the 0.7 threshold. It indicates that there is a high level of internal consistency in each measure. The total variance explained is 0.851 demonstrating that these eight dimensions account for a significant amount of the variance. For EF (Chronbach’s α = 0.813) for FR (α = 0.764) for SE (Chronbach’s α = 0.750), for FF (Chronbach’s α = 0.801), for SR (Chronbach’s α = 0.711), for pressure to eat (Chronbach’s α = 0.711) and for restriction (Chronbach’s α =0.751).

Children’s Appetite Traits

According to the collected data majority of children had less or moderate food approach and only2.9% (n=31) had extremely food approach. For avoidance tendency, almost three quarter of children moderately had this trait while 11.9% had less and 16.9% had it extremely (Table 3 & Table 4).

Parental feeding practices

Data regarding parents’ feeding practices shows that over half of parents (52%, n=563) exert pressure moderately, while 38.4% of them use it extremely and just a small number of parents (9.6%, n=104) employ that very few. On the other hand, implementing restriction as a feeding strategy is very popular among parents and around 90% of them use it moderately or extremely and only 10 percent hardly ever use it (Table 5).

Association between parental Feeding Practices and Children’s Appetite Traits

The statistical examination for parental feeding practices and children’s appetitive traits shows that parental pressure to eat was positively associated with child satiety responsiveness (r, 0.265), slowness (r, 0.253), and fussiness (r, 0.174) and negatively with food enjoyment (r, -0.214) and food responsiveness (r, - 0.142). Furthermore, “parental restriction” was positively associated with child food responsiveness (r, 0.183) and food enjoyment (r, 0.102) while there was not any correlation between restriction and any of food avoidance tendencies (Table 6).

Discussion

The present study examined associations between children’s eating behaviour and parental feeding practices. The children’s eating behaviour was classified as “approach tendency and “avoidance tendency”. The results of this study illustrate those parents who used pressure for controlling their child’s food intake had children who were less likely to have food responsiveness and enjoyment of food and were more likely to have satiety responsiveness, slowness in eating, and food fussiness. Alternatively, it is also possible that children whose parents use more pressure may learn to reject their parents’ requests to eat and these parents feeding practice may stimulated food avoidance tendency in children. However, a bidirectional relationship is possible (Ventura & Birch, 2008). It is likely that children whose parents use restriction for controlling their food intake may have food approach tendencies. Alternatively, it is also likely that children whose parents use more restriction may be interested to the restricted food and they overeat when it is freely available (Birch, Fisher, & Davison, 2003) (Figure 1).

Children’s Appetite Traits and Parental Feeding Practices

Various eating behaviour could be the consequence of different feeding practices, and alternatively parental different feeding practices could be the result of their children’s various eating behaviour or children’s characteristics such as age, birth order, physical appearance, specific abilities, gender and weight (Birch & Fisher, 2000). For instance, parents who assume their children have small appetite force them to enhance ingestion (Galloway & Birch, 2003) and (Webber, Cooke, Hill, & Wardle, 2010). Parents who perceive their children are underweight or thin also use this strategy (Gregory, Paxton, & Brozovic, 2010). In addition, children who are fussy, picky and slow eater arouse their parents to force them to eat. Therefore, a bidirectional relationship is possible. Restriction also follows the same trend, due to new life style which is largely attributed to broad-scale modifications in food and physical activity environment, parents tend to restrict their children’s access to junk food or even the amount of that. Parents who have overweight children in the family or perceive their children are at risk of being overweight, usually utilize this practice more (Francis, Hofer, & Birch, 2001; Keller, Pietrobelli, Johnson, & Faith, 2006; Fisher & Birch, 1999; Braet, Soetens, Moens, Goossens, & Vlierberghe, 2007). It seems parents use greater restriction for their overweight girls in compare with the overweight boys (Wardle, Sanderson, Guthrie, Rapoport; & Plomin, 2002). In fact, it may be useful to take an interactional perspective that children both influence and are influenced by their parents’ feeding practices. This will allow the development of targeted interventions and better parental guidance on managing obesogenic eating behaviours in young children (Webber, Cooke, Hill, & Wardle, 2010).

Limitations and Strengths

This research had a number of limitations. It’s reliance on parental self report is one of the main limitations. The other is inability to demonstrate causal relationships; the data obtained via questionnaires allowed conclusions only about relationships between children’s appetites and parental feeding practices and did not address the question of whether decreased appetites among children increased parental pressure to eat or if the reverse were the case. Further this study was cross- sectional in design, longitudinal research is needed to recognize the causal direction of the relationships between children’s eating behaviour and parental feeding practices. Future research is necessary to build on this study’s results and address its limitations. In spite of the limitations, this study is strengthened by having a wide range of ethnic diversity (55 different nationalities) which may give the opportunity to generalize the result to different nations.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the study results suggest that pressure to eat and restriction has counterproductive effect on children eating behaviour. The outcome of restriction does not seem pleasing; Fisher and Birch (1999) set forth when parents make limitation to access palatable foods for their children, they assume they are controlling their children’s junk foods intake but in reality they increase the intake of those foods. For pressure there is also reverse effect, it means children whose parents force them to eat tend to be more difficult to please with meals. Although avoidance tendency traits are not recommendable, according to contemporary life style which expose people to the risk of being overweight or obese, scientists believe that this tendency can be protective in some way due to limited child’s options since the child has a lot of dislikes (Webber, Hill, Cooke, Carnell, & Wardle, 2010; Jacobi, Agras, Bryson, & Hammer, 2003; Dovey, Staples, Gibson, & Halford, 2008). Finally, parents have a very significant role in making good eating habits in their children since it will be with them for the rest of their life and determine children health trend (physically and psychologically). Having at least one Family meal daily can work as a chance for parents to be a role model for children which in turn affect their food preference, attitudes and eating patterns. Family meals together can raise children’s healthy eating habits (Fulkerson, Neumark-Sztainer, & Story 2006). Parents cannot merely force their children to eat something and not to eat others. They should review whatever they have done because children follow what parents did, not what they say.

Acknowledgements

The author(s) declare that there is no conflict of interest. We thank all the schools principals and parents of Dubai privet schools who took part in this study for their time and help.

References

Birch, L. L. & Fisher, J. O. (2000). Mothers' child-feeding practices influence daughters' eating and weight. Am J Clin Nutr, 71(5), 1054-61. DOI:

Birch, L. L. (2006). Child Feeding Practices and the Etiology of Obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring), 14(3), 343–344. DOI:

Birch, L. L., Fisher, J. O. & Davison, K.K. (2003). Learning to overeat: maternal use of restrictive feeding practices promotes girls' eating in the absence of hunger. Am J Clin Nutr, 78(2), 215-20. DOI:

Birch, L. L., Fisher, J. O., Grimm-Thomas, K., Markey, C. N., Sawyer, R., & Johnson, S. L. (2001). Confirmatory factor analysis of the Child Feeding Questionnaire: a measure of parental attitudes, beliefs and practices about child feeding and obesity proneness. Appetite, 36(3), 201–210. DOI:

Braet, C., Soetens, B., Moens, E., Goossens, S. M., & Vlierberghe L. V. (2007). Are two informants better than one? Parent-child agreement on the eating styles of children who are overweight. Eur Eat Disord Rev, 15(6), 410-417. DOI:

Brown, R., & Ogden, J. (2004). Children’s eating attitudes and behaviour: a study of the modeling and control theories of parental influence. Oxford Journals, 19(3), 261-271. DOI:

Campbell, K. J., Crawford, D. A., & Ball, K. (2006). Family food environment and dietary behaviors likely to promote fatness in 5-6 year-old children. Int J Obes (Lond), 30(8), 1272-80. DOI:

Carnell, S., & Wardle, J. (2007). Measuring behavioural susceptibility to obesity: Validation of the child eating behaviour questionnaire. Appetite, 48(1), 104-113. DOI:

Carruth, B. R., & Skinner, J. D. (2000). Revisiting the picky eater phenomenon: neo-phobic behaviors of young children. J Am Coll Nutr, 19(6), 771-80. DOI:

Dovey, T. M., Staples, P. A., Gibson, E. L. & Halford, J. C. G. (2008). Food neo-phobia and ‘picky/fussy’ eating in children: a review. Appetite, 50, 181-193. DOI:

Farrow, C., Galloway, A. T., & Fraser, K. (2009). Sibling eating behaviours and differential child feeding practices reported by parents. Appetite, 52, 307-312. DOI:

Fisher, J. O., & Birch, L. L. (1999). Restricting access to palatable foods affects children's behavioral response, food selection, and intake. American Society for Clinical Nutrition, 69(1), 264-272. DOI:

Fisher, J. O., & Birch, L. L. (1999). Restricting access to foods and children's eating. Appetite, 32(3), 405-419. DOI:

Fisher, J. O., Mitchell, D. C., Smiciklas-Wright, H., & Birch, L. L. (2002). Parental influences on young girls' fruit and vegetable, micronutrient, and fat intakes. Am Diet Assoc, 102(1), 58-64. DOI:

Francis, L. A., Hofer, S. M., & Birch, L. L. (2001). Predictors of maternal child-feeding style: maternal and child characteristics. Appetite, 37(3), 231-43 DOI:

Fulkerson, J. A., Neumark-Sztainer, D., & Story, M. (2006). Adolescent and parent views of family meals. Journal of American Dietetic Association, 106(4), 526-532. DOI:

Galloway, A. T., Fiorito, L., Lee, Y., & Birch, L. L. (2005). Parental pressure, dietary patterns, and weight status among girls who are "picky eaters". Am Diet Assoc, 105(4), 541-548. DOI:

Galloway, A. T., Fiorito, L. M., Francis, L. A., & Birch, L. L. (2006). 'Finish your soup': counterproductive effects of pressuring children to eat on intake and affect. Appetite, 46(3), 318-23. DOI:

Galloway, A. T., Lee, Y., & Birch, L. L. (2003). Predictors and consequences of food neophobia and pickiness in young girls. Am Diet Assoc, 103(6), 692-698. DOI:

Gregory, J. E., Paxton, S. J., & Brozovic, A. M. (2010). Maternal feeding practices, child eating behaviour and body mass indexin preschool-aged children: a prospective analysis. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 55 DOI:

Jacobi, C., Agras, W. S., Bryson, S., & Hammer, L. D. (2003). Behavioral validation, precursors, and concomitants of picky eating in childhood. Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 42(1), 76-84. DOI:

Keller, K. L., Pietrobelli, A., Johnson, S. L., & Faith, M. S. (2006). Maternal restriction of children's eating and encouragements to eat as the 'non-shared environment': a pilot study using the child feeding questionnaire. Int J Obes (Lond), 30(11), 1670-5. DOI:

Nordin, S., Broman, J., Garvill, D. A., & Nyroos, M. (2004). Gender differences in factors affecting rejection of food in healthy young Swedish adults. Appetite, 295–301. DOI:

Russell, C. G., & Worsley, A. (2008). A population-based study of preschoolers' food neophobia and its associations with food preferences. J Nutr Educ Behav, 40(1), 11-19. DOI:

Scaglioni, S., Salvioni, M., & Galimberti, C. (2008). Influence of parental attitudes in the development of children eating behaviour. British Journal of Nutrition, 99(1). 22-25. DOI:

Sleddens, F. C. E., Kremers, P. J. S., & Thijs, C. (2008). The Children's Eating Behaviour Questionnaire: factorial validity and association with Body Mass Indexin Dutch children aged 6–7. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 5, 49. DOI:

Tan, C. C., & Holub, S. C., (2012). Maternal feeding practices associated with food neophobia. Appetite, 483-487. DOI:

Ventrura, A. K., & Birch, L. L. (2008). Does parenting affect children's eating and weight status? International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 5, 15. DOI:

Wardle, J., Carnell, S., & Cooke, L. (2005). Parental control over feeding and children's fruit and vegetable intake: how are they related? J Am Diet Assoc, 105(2), 227-232. DOI:

Wardle, J., Guthrie, A. C., Sanderson, S., & Rapoport, L. (2001). Development of the Children's Eating Behaviour Questionnaire. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 42(7), 963–970. DOI:

Wardle, J., Sanderson, S., Guthrie, C. A., Rapoport, L., & Plomin, R. (2002). Parental feeding style and the intergenerational transmission of obesity risk. Obesityresearch, 10(6), 453-462. DOI:

Webber, L., Cooke, L., Hill, C., & Wardle, J. (2010). Adiposity and maternal feeding practices: a longitudinal analysis. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 92(6),1423-1438. DOI:

Webber, L., Cooke, L., Hill, C., & Wardle, J. (2010). Associations between Children's Appetitive Traits and Maternal Feeding Practices. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 110(11), 1718-1722. DOI:

Webber, L., Hill, C., Cooke, L., Carnell, S., & Wardle, J. (2010). Associations between child weight and maternal feeding styles are mediated by maternal perceptions and concerns. Eur J Clin Nutr, 64(3), 259-265. DOI:

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.